Chapter 50

Deep Vein Thrombosis

1. What three primary factors promote venous thromboembolic (VTE) disease?

Development of venous thrombosis is promoted by the following (the Virchow Triad):

2. List the risk factors for thromboembolic disease.

The numerous risk factors for thromboembolic disease include surgery, trauma, immobility, cancer, pregnancy, prolonged immobilization, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, and acute medical illnesses. A more complete listing of these risk factors is given in Box 50-1.

3. What is the natural history of venous thrombosis?

Resolution of fresh thrombi occurs by endogenous fibrinolysis and organization. Fibrinolysis results in actual clot dissolution. Organization reestablishes venous blood flow by restoring endothelial cells and incorporating into the venous wall residual clot not dissolved by fibrinolysis. Incomplete recanalization can cause postphlebitic syndrome in >20% of patients.

4. Can patients with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) be accurately diagnosed clinically?

5. Where is the most common origin for thrombi that result in pulmonary emboli?

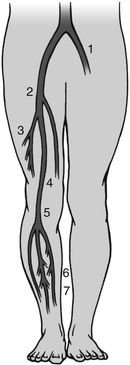

Thromboses in the deep veins of the lower extremities (Fig. 50-1) account for 90% to 95% of pulmonary emboli. Less common sites of origin include thromboses in the right ventricle, in upper extremity, prostatic, uterine, and renal veins; and, rarely, in superficial veins.

Figure 50-1 Common sites of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in the lower body. 1, Left iliac vein; 2, common femoral vein; 3, termination of deep femoral vein (profunda femoris); 4, femoral vein; 5, popliteal vein at adductor canal; 6, posterior tibial vein; 7, intramuscular veins of calf. (From Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC: Pfenninger and Fowler’s procedures for primary care, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

6. How is the diagnosis of lower extremity DVT confirmed?

Contrast venography is no longer appropriate as the initial diagnostic test in patients exhibiting DVT symptoms, although it remains the gold standard for confirmatory diagnosis of DVT. It is nearly 100% sensitive and specific and provides the ability to investigate the distal and proximal venous system for thrombosis. Venography is still warranted when noninvasive testing is inconclusive or impossible to perform, but its use is no longer widespread because of the need for administration of a contrast medium and the increased availability of noninvasive diagnostic strategies.

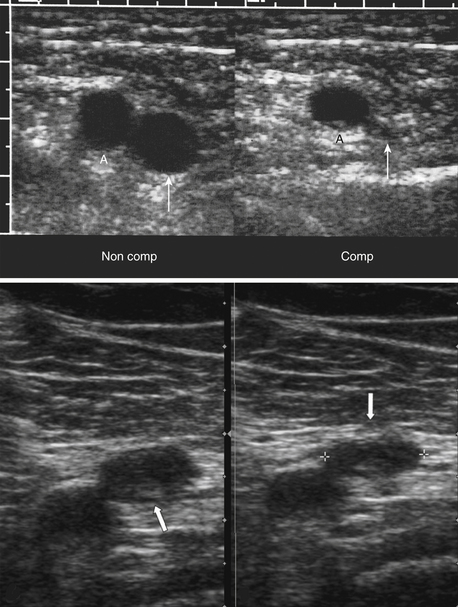

Ultrasound is safe and noninvasive and has a higher specificity than impedance plethysmography for the evaluation of suspected DVT. With color flow Doppler and compression ultrasound, DVT is diagnosed based on the inability to compress the common femoral and popliteal veins (Fig. 50-2). In patients with lower extremity symptoms, the sensitivity is 95% and specificity 96%. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound in asymptomatic patients, those with recurrent DVT, or those with isolated calf DVT is less reliable. The sensitivity of ultrasound improves with serial testing in untreated patients. Repeat testing at 5 to 7 days will identify another 2% of patients with clots not apparent on the first ultrasound. Serial testing can be particularly valuable in ruling out proximal extension of a possible calf DVT. Because the accuracy of ultrasound in diagnosing calf DVT is acknowledged to be lower (81% for DVT below the knee versus 99% for proximal DVT), follow-up ultrasounds at 5 to 7 days are reasonable because most calf DVTs that extend proximally will do so within days of the initial presentation.

Figure 50-2 Normal and abnormal compression of the femoral vein with ultrasound examination. Top Images: Transverse image of the femoral artery (A) and vein (thin white arrow) before (Non Comp) and after (Comp) compression with the sonographic transducer, demonstrated normal vein collapse with compression. Bottom Images: There is minimum compression of the common femoral vein (thick white arrow) in this patient with deep vein thrombosis. (Top images from Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW, Levine D: Diagnostic ultrasound, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2010, Mosby. Bottom images from Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin T, et al: Murray and Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

7. When should prophylaxis of DVT be considered?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree