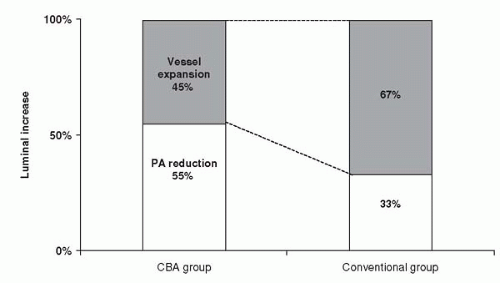

shift for 33% of luminal enlargement (Fig. 11.1). The vessel expansion ratio was significantly smaller after cutting balloon angioplasty than after conventional angioplasty (1.05 versus 1.22; p <0.05). These findings suggest that the predominant mechanism of dilatation after cutting balloon angioplasty is plaque compression or shift rather than vessel expansion, unlike in conventional angioplasty.

complex lesions, including ostial and bifurcated lesions. Cutting balloons also are useful as an adjunct to brachytherapy for in-stent restenosis and in bare metal stenting in vessels larger than 3 mm.

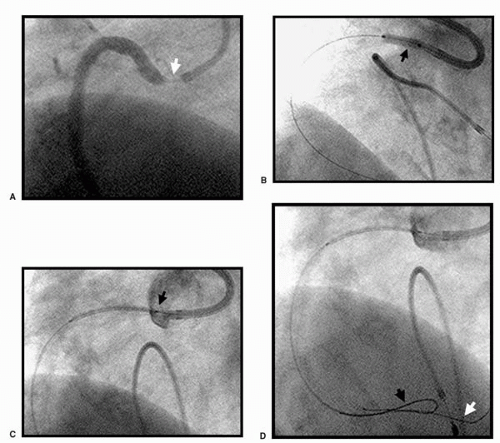

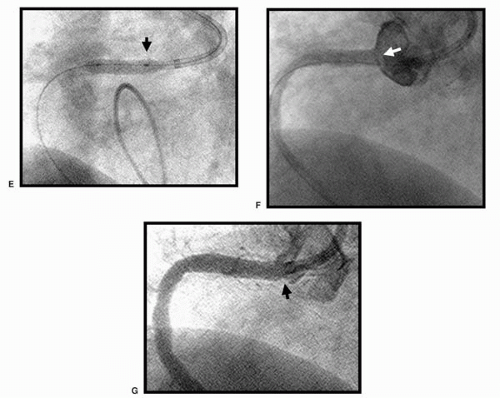

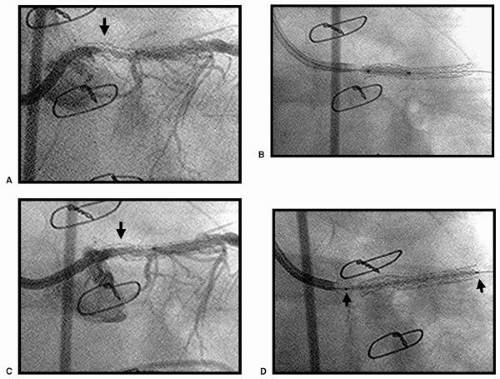

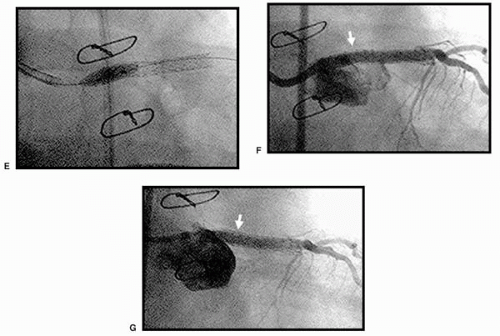

registries (54, 55, 56, 57, 58). Direct stenting and conventional BA in bifurcation lesions may cause plaque shifting. The cutting balloon has been demonstrated to minimize plaque shifting (59). Pretreatment using a sequential cutting balloon inflation in bifurcation lesions before stent deployment in the main vessel, followed by final kissing balloon inflation in both vessels, is one possible approach to the management of bifurcation lesion stenting. Provisional stenting of the side-branch vessel is done when suboptimal results are encountered. In short focal lesions, the cutting balloon is only 6 mm in length, thus controlling the injury zone, when compared to predilatation with a conventional balloon.

were randomized, with 153 patients in the cutting balloon group and 153 in the convention angioplasty group (60).

TABLE 11.1. CUBA TRIAL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

randomized to cutting balloon treatment, and 621 to coronary angioplasty. The mean reference vessel diameter was 2.86 ± 0.49 mm, mean lesion length 8.9 ± 4.3 mm, and prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients was 13%.

TABLE 11.2. CUTTING BALLOON GLOBAL RANDOMIZED TRIAL QUANTITATIVE ANGIOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

angioplasty with conventional BA in small coronary arteries, less than 3 mm in diameter (74).

TABLE 11.3. CBASS TRIAL | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 11.4. CAPAS TRIAL

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|