Coronary Stenting

Mauro Moscucci, MD, MBA

INTRODUCTION

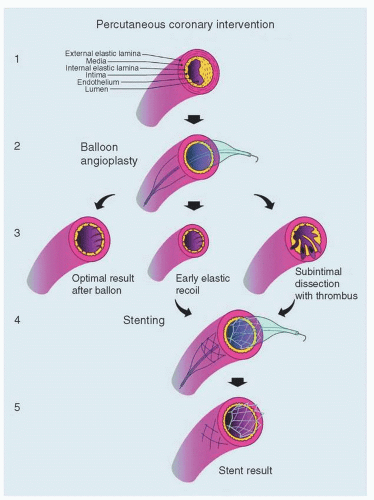

Since the first coronary angiography performed by Marvin Stones in 1958, the history of interventional cardiology has been characterized by the work of many pioneers and critical milestones (FIGURE 20.1). In this chapter, we will provide a visual overview of the evolution of coronary stenting. As stated in Chapter 18, the improvement in lumen diameter following balloon angioplasty is secondary to local dissection and vessel stretch. Unfortunately, major limitations of balloon angioplasty beyond heavy calcification and other lesion characteristics include the development of abrupt closure due to uncontrolled dissection and the development of restenosis secondary to a combination of elastic recoil, intimal hyperplasia, and vascular remodeling (Table 20.1; FIGURES 20.2 and 20.3). By providing a scaffolding system to the artery, coronary stents reduce the risk of abrupt closure secondary to local dissection, they overcome elastic recoil, and they can optimize final lumen diameter and reduce the risk of restenosis. Thus, the introduction of coronary stenting has created a true revolution in interventional cardiology. The objective of this chapter is to provide an historical, chronological, and visual overview of coronary stenting (FIGURES 20.4, 20.5, 20.6, 20.7, 20.8, 20.9, 20.10, 20.11, 20.12, 20.13, 20.14, 20.15, 20.16, 20.17, 20.18, 20.19, 20.20, 20.21, 20.22, 20.23, 20.24, 20.25, 20.26, 20.27, 20.28, 20.29, 20.30, 20.31, 20.32, 20.33, 20.34, 20.35, 20.36, 20.37, 20.38, 20.39, 20.40, 20.41, 20.42, 20.43, 20.44, 20.45, 20.46, 20.47, 20.48, 20.49, 20.50 and 20.51).

LIMITATIONS OF PERCUTANEOUS TRANSLUMINAL CORONARY ANGIOPLASTY (PTCA)

See Table 20.1.

TABLE 20.1 Limitations of Conventional PTCA | |

|---|---|

|

DEFINITIONS OF RESTENOSIS

Restenosis can be defined according to angiographic findings at follow-up angiography (angiographic restenosis) and clinically driven revascularization of the target site. Importantly, studies have shown that restenosis rates and target vessel revascularization rates tend to be higher when angiographic follow-up is performed on a routine base. Thus, the concept of “clinical restenosis,” defined as clinically driven target lesion and target vessel revascularization, has been developed as a clinically meaningful surrogate of angiographic restenosis (Table 20.2).

TABLE 20.2 Angiographic Restenosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BALLOON ANGIOPLASTY AND STENTING

The word “stent” was introduced in 1916 by Johannes Esser, a Dutch plastic surgeon, to describe oral splints developed to scaffold the mouth by Charles Stent, a British dentist.1,2 Other theories regarding the origin of the world stent trace it as back as the late 14th century to the Anglo-French word extente, (“valuation of land, stretch of land”) and derived from the old French extendre “extend” and from Latin “extendere.”3,4 As of today, the definitions according to the Oxford English Living Dictionaries include (1) “A splint placed temporarily inside a duct, canal,

or blood vessel to aid healing or relieve an obstruction” and “An impression or cast of a part or body cavity, used to maintain pressure so as to promote healing, especially of a skin graft” originating from the name of Charles Stent. (2) An assessment of property made for purposes of taxation. (From Old French estente “valuation,” related to Anglo-Norman French extente.)5

or blood vessel to aid healing or relieve an obstruction” and “An impression or cast of a part or body cavity, used to maintain pressure so as to promote healing, especially of a skin graft” originating from the name of Charles Stent. (2) An assessment of property made for purposes of taxation. (From Old French estente “valuation,” related to Anglo-Norman French extente.)5

FIGURE 20.4 A and B, Coil spring tubular prosthesis and percutaneous placement described by Charles Dotter in 1969. In an attempt to overcome the frequent reocclusion of the femoral artery following angioplasty, Dotter begun experimenting with the insertion of different type of tubing. He found that while various plastic tubes would clot, an open coil-spring configuration promoted long-term patency.6 Reproduced with permission from Dotter CT. Transluminally-placed coilspring endarterial tube grafts. Long-term patency in canine popliteal artery. Invest Radiol. 1969;4:329-332. |

FIGURE 20.5 Four early endovascular stents. A, The upper left panel show Dotter’s early nitinol coil wire stent compacted for placement and after heat-induced expansion to its predetermined dimensions7.B, The zigzag expanding stainless steel stent described by Wright et al.8 shown in the upper right panel in both its sheathed and unsheathed forms. C, The lower left panel shows the stents developed by Maass et al.9 D, The lower right panel shows the balloon expandable stainless steel Palmaz stent.10 Reproduced with permission from Ruygrok PN, Serruys PW. Intracoronary stenting. Circulation. 1996;94:882-890.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|