Description

Thrombosis

Non-atherosclerotic Intimal Lesions

Intimal hyperplasia

Accumulation of smooth muscle cells in the intima, in the absence of lipids or macrophage foam cells (Fig. 5.1).

Absent

Intimal xanthoma (fatty streak)

Intimal accumulation of foam cells without a necrotic core or fibrous cap. These lesions usually regress (Fig. 5.2).

Absent

Progressive atherosclerotic lesions

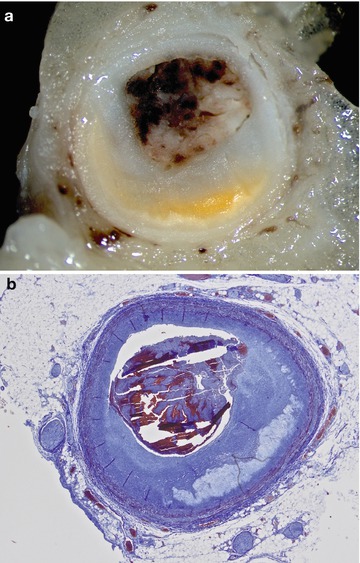

Pathologic intimal hyperplasia (Juvenile atheromatosis)

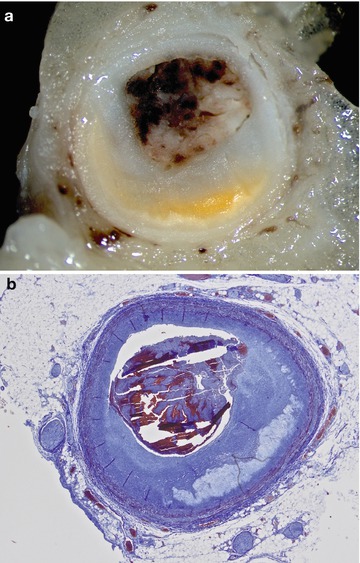

Smooth muscle cells in a matrix rich in proteoglycans with areas of extracellular lipid accumulation without necrosis (Fig. 5.3).

Absent

Erosion

Luminal thrombosis in direct contact with the intima over an area with no endothelium. Plaque with the same characteristics as above.

Thrombus mostly mural and non-occlusive

Fibrous cap atheroma (Stable plaque)

Absent

Erosion

Luminal thrombosis in direct contact with the intima over an area with no endothelium, but without communication with the necrotic core. Plaque with the same characteristics as above.

Thrombus mostly mural and non-occlusive

Thin fibrous cap atheroma (Vulnerable plaque)

Thin fibrous cap infiltrated by macrophages and lymphocytes, with few smooth muscle cells and an underlying necrotic core (Fig. 5.6).

Absent. Intraplaque haemorrhage may be present

Plaque rupture

Fibroatheroma with fibrous cap rupture. Occlusive thrombosis in communication with the necrotic core

Thrombus, generally occlusive

Calcified nodule

Calcified nodule which protrudes through the fibrous cap to the lumen. There is neither endothelium nor inflammatory infiltrates in that area.

Thrombus usually non-occlusive

Fibrocalcific plaque

Collagen-rich plaque with significant luminal stenosis. Lesions usually contain large areas of calcification with few inflammatory cells. A necrotic core may be present (Fig. 5.7).

Absent

Fig. 5.1

Intimal hyperplasia

Fig. 5.2

Intimal xanthoma

Fig. 5.3

Pathological intimal hyperplasia. (a) Macroscopic image. (b) Microscopic image

Fig. 5.4

Fibrous cap atheroma (stable plaque). Coronary artery with two plaques facing each other. To the right, atheroma with necrotic core surrounded by a thick fibrous cap

Fig. 5.5

Fibroatheroma (stable plaque). More developed atheroma plaque, with a large necrotic core focally calcified containing numerous cholesterol crystals and overlaid by a thick fibrous cap. Lumen reduction is >75 %

Fig. 5.6

Atheroma with thin fibrous cap (vulnerable plaque). Necrotic core protruding towards the lumen, overlaid by a very thin yet still complete fibrous cap

Fig. 5.7

Fibrocalcific plaque. Almost circumferential calcific plaque that causes a lumen reduction >85 %

At the level of the coronary arteries, these lesions can compromise one, two or the three epicardial coronary arteries. Autopsy findings are very diverse since the involvement of just one vessel ranges from 15 to 26 %, of two vessels between 27 and 39 % and of three vessels from 33 to 62 %.

In deceased young people, only one vessel tends to be affected and the lesion is located mainly in the proximal third of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, just distal to the left coronary trunk bifurcation. There is a haemodynamic explanation for this favoured location since at this point the speed of the blood flow is critically reduced and the vessel wall experiences more traction. In contrast, CAD in adults and the elderly usually affects several of the coronary arteries, the LAD coronary artery, the right coronary artery (RCA) and the left circumflex artery (LCx).

Plaques seen in young people who die from sudden cardiac death (SCD) due to CAD consist of a combination of cellular and dense fibrous tissues in the intima (fibrocellular plaque) (Figs. 5.8, 5.9, 5.10, 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, and 5.14) (Table 5.2). In contrast, plaques examined in adults and the elderly are characterized by a large lipid core (fibrolipid plaque) that can calcify and lead to a fibrocalcific plaque (Fig. 5.7).

Fig. 5.8

Fibrocellular plaque. Fibrotic plaque in a 31-year-old male who died suddenly whilst at rest. (a) A whitish plaque with a fibrotic appearance can be appreciated, causing a lumen reduction greater than 90 %. A very small yellowish fatty streak can be observed at the bottom of the image. (b) Significant intimal hyperplasia consisting of smooth muscle cells with little fibrosis. A small mural thrombus due to plaque erosion can be appreciated in the vessel lumen (Masson’s trichrome)

Fig. 5.9

Pathological intimal hyperplasia. A 33-year-old woman with previous personal and familial history of hypercholesterolaemia, who died whilst sleeping. (a) A whitish plaque can be appreciated in the proximal third of the LAD, which causes luminal stenosis greater than 75 %. (b) Histologically, pathological intimal hyperplasia with a macrophage-formed small lipid core can be observed

Fig. 5.10

(a) Detail of the medial layer with a small lipid core. (b) Detail of intimal hyperplasia. (c) Higher magnification of the lipid cells and some apoptotic smooth muscle cells

Fig. 5.11

A 32-year-old male with a history of cocaine abuse who died suddenly at home. A toxicological analysis excluded the presence of cocaine. (a) Plaque in the RCA with a significant lipid core and severe luminal stenosis. (b) Microscopic image (Masson’s trichrome)

Fig. 5.12

A 35-year-old male with a history of morbid obesity, dyslipidemia and heavy smoking who died suddenly whilst having sexual intercourse. (a) Luminal stenosis of around 95 % in the LAD. (b) Microscopic image, where a calcific plaque with haemorrhage, thick fibrous cap and severe stenosis can be observed

Fig. 5.13

A 46-year-old woman who died suddenly whilst sleeping. (a) Plaque with lipid appearance that causes luminal stenosis greater than 75 % in the LAD. (b) Fibrolipid plaque with large necrotic core and thick fibrous cap (stable plaque)

Fig. 5.14

A 51-year-old male with a history of schizophrenia who died suddenly whilst sleeping. (a) A fibrous plaque can be observed in the proximal tract of the LCx artery which causes luminal stenosis of around 90 %. The RCA also presented with a similar type of plaque (two-vessel disease). (b) Histological image of an occlusive fibrous plaque with haemorrhagic foci (Masson’s trichrome)

Table 5.2

Clinico-pathological correlation of coronary atherosclerosis

Stable angina |

Stenosis greater than 75 % of the lumen. |

Unstable angina |

Plaque rupture with mural thrombus. |

Acute infarction |

Plaque rupture and occlusive thrombus. |

Sudden death |

One or more of the following lesions can be found: |

Stenosis greater than 75 % in one or more of the main coronary artery trunks. |

Rupture or erosion of the plaque with mural or occlusive thrombosis. |

Acute myocardial infarction. |

Scarring from a healed myocardial infarction. |

The degree of calcification, determined by coronary CT angiography, has been used as a marker for atherosclerosis. These studies show a strong correlation between the levels of calcium in the coronary plaque and the risk of suffering cardiovascular events. Nevertheless, the presence of calcification is a poor predictor of the degree of coronary stenosis in a specific coronary segment.

5.3 Atheroma Plaque Complications

As previously mentioned, an atheroma plaque, as an encapsulated fatty mass, is analogous to an abscess contained within a fibrous capsule, and as such, can suffer erosion or rupture. Erosion or rupture of the fibrous cap exposes the atheromatous material to the flowing blood components, initiating the process of platelet aggregation and coagulation that will ultimately lead to thrombus formation.

To fully understand the complications of the atheroma plaque it is important to mention the concept of vulnerable or unstable plaque, a term that has been used to define those atherosclerotic plaques that are especially prone to rupture. The vulnerable plaque has a thin fibrous cap overlying a large lipid core (Fig. 5.6). Accordingly, the mechanisms of plaque rupture or erosion are related to thinning and inflammation of the fibrous cap. Both erosion and rupture of a plaque are the basis for the development of a platelet thrombus that can be either mural or occlude the entire vessel lumen (occlusive).

The percentage of coronary thrombosis in different autopsy series studying ischaemic sudden death ranges from 20 to 70 %. These wide variations can be due to the population studied (timeframe between the onset of symptoms and death, presence of acute myocardial infarction, type of prodromic symptoms) and the type of pathological examination performed (macroscopic or histologic). Based on the experience from the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences in Madrid, thrombosis was observed in 37 % of the cases of ischaemic heart disease; however, this value increased to 56 % in people under 40 years of age.

Coronary thrombosis can be secondary to three distinct processes:

(a)

Plaque erosion: Characterized by acute thrombosis in direct contact with the intima. It is more frequent in people aged 30–50 years, with no gender preference, and is associated with tobacco, especially in premenopausal women, although there is also a heritable component. Generally the process of plaque erosion occurs in stenosis of less than 70 % of the lumen (Figs. 5.15, 5.16, 5.17, 5.18, 5.19, and 5.20). It is observed in 70–75 % of SCD due to coronary thrombosis.

Fig. 5.15

Plaque erosion. A 34-year-old woman who died after presenting with chest pain radiating to the shoulders. (a, b) There was an occlusive platelet thrombus over a fibrous cap with intimal thickening and without necrotic core in the LAD coronary artery. The anterior wall of the LV showed an early acute myocardial infarction (see Fig. 5.28)

Fig. 5.16

A 34-year-old male with no previous relevant medical history who died suddenly at home. (a) Image of a fresh fibrolipid atheroma plaque with occlusive thrombosis in the proximal third of the LAD coronary artery. (b) Erosion in the plaque edges can be appreciated, which determines an acute occlusive thrombosis. (c) Detail of the erosion in one of the plaque edges (Masson’s trichrome)

Fig. 5.17

A 44-year-old male, smoker, who died suddenly in the street. (a) An eccentric atheroma plaque with a small lipid core and acute occlusive thrombosis in the proximal third of the LAD coronary artery. (b) Microscopic image of the acute occlusive thrombosis due to plaque erosion (Masson’s trichrome)

Fig. 5.18

A 43-year-old male, in prison, with a history of drug abuse, who died suddenly. (a) Serial sectioning of the LAD coronary artery shows eccentric haemorrhage and occlusive thrombosis along a portion of 2 cm. (b) Microscopic examination reveals a haemorrhage, a fibrin thrombus attached to the intima, and a superimposed occlusive platelet thrombosis

Fig. 5.19

A 54-year-old woman, without known medical history, who died suddenly in bed. A small intraplaque haemorrhage and acute occlusive thrombosis in the proximal third of the LAD coronary artery can be appreciated

Fig. 5.20

A 63-year-old male, with a history of dyslipidemia, who died suddenly whilst driving. (a, b) Acute occlusive thrombosis due to plaque erosion can be appreciated in the proximal third of the RCA (Masson’s trichrome)

(b)

Plaque rupture: Characterized by an interruption in the fibrous cap with acute thrombosis in continuity with the underlying lipid core. According to some authors, plaque rupture is present in 25–30 % of SD that occurs from coronary thrombosis, and is more frequent in males than in females between the ages of 35–80 years. It tends to be associated with dyslipidemia, diabetes and tobacco (Figs. 5.21 and 5.22).

Fig. 5.21

Plaque rupture. An 86-year-old male, smoker, without other relevant personal history, who died suddenly whilst shaving in the bathroom. A calcific plaque in the RCA with necrotic core and acute thrombosis due to plaque rupture can be appreciated. There is continuity between the thrombus and the necrotic lipid core

Fig. 5.22

Plaque rupture. A 77-year-old male, with hypertension, who was found dead in the bathroom. (a) Low magnification image of the RCA showing a large plaque rich in cholesterol crystals with intraplaque haemorrhage and rupture of the thin fibrous cap. (b) Higher magnification image where a platelet thrombus around the area of fibrous cap rupture can be appreciated (Masson’s trichrome). The stenosis of the coronary artery was >80 % and there was AMI in the posterior wall of the LV and a healed infarction in the anterior wall

(c)

Calcified nodule: More infrequent than the two previous processes. It refers to a heavily-calcified plaque in which there is a rupture of the fibrous cap and the thrombus is associated with a protruding and calcified nodule. It appears in the elderly, and it is more common in men than in women. This lesion, more frequent in the carotid arteries, tends to be related with the onset of intraplaque haemorrhage.

It is important to be aware that in up to 50 % of the cases of SCD, coronary thrombosis settles in plaques with less than 75 % luminal stenosis. On the other hand, it has also been demonstrated that in 10 % of SCD from CAD, there is neither necrotic core nor fibroatheroma formation, and this situation is much more frequent in young people.

Other lesions may occur in the atheroma plaques, not related to thrombosis such as intraplaque haemorrhage (Figs. 5.23 and 5.24), healed erosion/rupture and recanalization of an old occlusive thrombus (Figs. 5.25 and 5.26).

Fig. 5.23

Fibroatheroma with intraplaque haemorrhage. A 64-year-old male, with a history of hypertension, who died suddenly after playing a paddle game. A heavily calcific plaque and intraplaque haemorrhage can be appreciated in the RCA. Luminal stenosis greater than 75 %

Fig. 5.24

Intraplaque haemorrhage. A 45-year-old male, heavy smoker (40 cigarettes/day), who died suddenly at home. He had suffered from chest pain radiating to the left shoulder for several days and, because of this, he was attended at the hospital emergency department. Diagnosis was “atypical thoracic pain”. A massive intraplaque haemorrhage, almost occlusive, can be appreciated in the proximal third of the posterior descending coronary artery, together with a haemorrhagic infiltrate in the epicardial white adipose tissue

Fig. 5.25

Recanalized thrombosis. (a) A 45-year-old woman, without known previous medical history, who died at home. Fibrolipid plaque with necrotic core in the LAD coronary artery, intraplaque haemorrhage and recanalized thrombus. (b) Histological image from another case of recanalized thrombosis (Masson’s trichrome)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree