Methods of Sampling

The practicing pathologist will encounter coronary atherosclerosis primarily at autopsy. Because of the high prevalence of the disease in adults, the majority of autopsies will demonstrate some degree of coronary artery disease, whether incidental or relevant.

There are two major methods of in vivo sampling of coronary atherosclerosis as a surgical specimen: percutaneous via catheters, and open procedures. Coronary atherectomy was at one time a standard treatment for coronary stenosis, with catheter-based removal of the plaque or thrombus. Studies of directional coronary atherectomy showed an increase in hemorrhage into plaque, thrombosis, and lipid-rich plaque in patients with unstable coronary syndromes compared to those with stable angina.

1 “Plain old balloon angioplasty” (POBA) is still occasionally performed, however, which is a procedure that includes balloon dilatation of the lesion without stenting.

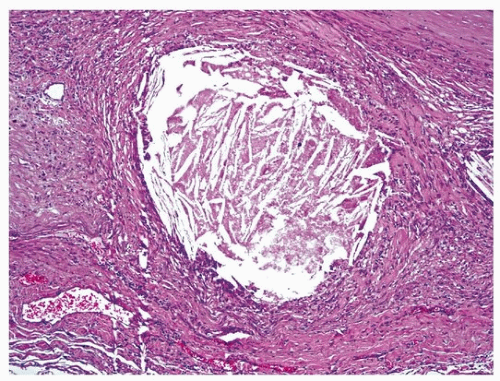

2Coronary thrombosuction, or thrombus aspiration, is occasionally performed in conjunction with balloon angioplasty studies, yielding pathologic information about the type and duration of the thrombus, including the presence of organizing thrombus, which is associated with a poor prognosis, and plaque components such as cholesterol crystals and calcification.

3,4Coronary endarterectomy (surgical removal of intimal disease, usually with concomitant bypass grafting) is not commonly performed because of relatively high rates of restenosis. However, in patients with severe diffuse disease not amenable to bypass, the surgeon may excise lengths of coronary plaques, which will be sent for pathologic examination.

5 Multiple arteries may undergo endarterectomy, with patch plasty of the left internal mammary artery. Minimally invasive surgery with off-pump techniques has been employed.

5,6,7

Examination of the Coronary Arteries at Autopsy

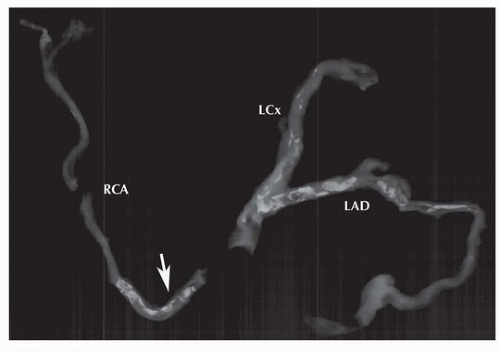

Ideally, coronary arteries should be sampled at 3- to 5-mm intervals to exclude coronary atheroscleroticlesions and thrombi (see

Chapter 138). Postmortem radiographs for assessment of the degree of calcification and time necessary for decalcification may be indicated for coronary deaths (

Fig. 150.1). When arteries are significantly calcified, they should be removed from the heart prior to sectioning for decalcification.

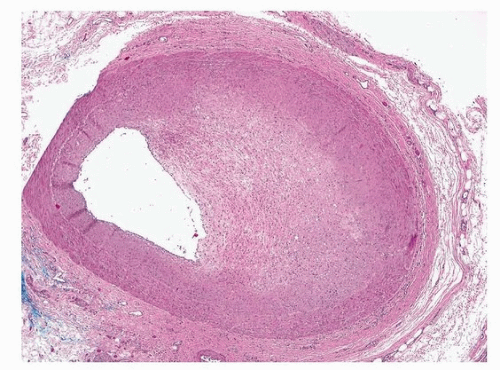

If accurate measurements of cross-sectional luminal narrowing are to be undertaken, perfusion fixation is necessary, as there is collapse of arterial walls rendering overestimation of percent stenosis, especially in eccentric lesions (

Fig. 150.2). The coronaries are perfusion fixed with 10% buffered formaldehyde retrograde from the ascending aorta at 100 mm Hg pressure for at least 5 minutes. A synthetic or rubber plug or stopper with central tubing is inserted into the aorta, taking care that the plug does not touch the aortic valve. The plug is attached to the tubing that is connected to the perfusion chamber that is placed 135 cm above the specimen, approximately equivalent to 100 mm Hg.

If a perfusion apparatus is not available, one can connect a polyethylene tube to a formalin spigot at one end and place the other end of the tube in the ascending or descending thoracic aorta, with the heart in a container on the floor. The spigot is opened, and leakage of formalin from the aorta is prevented with clamps.

The coronary arteries are then fixed in a distended state that approximate the dimensions observed in living patients. The method requires patency of the aortic valve to allow pressure filling of the coronaries.

Assessing Degree of Stenosis of Coronary Atherosclerosis at Autopsy

The accepted level of critical stenosis at autopsy that could result in ischemia or sudden death is 75% cross-sectional area narrowing of the lumen. By angiography, percent stenosis is determined as diameter narrowing of the column of contrast, compared to a proximal reference segment. However, at autopsy, cross sections of the arteries are taken, and percent narrowing is defined by cross-sectional area luminal narrowing. If plaques are concentric, a critical 75% area reduction (as seen on the glass slide) is comparable to a 50% narrowing as seen by angiography.

For correlation with premortem angiography, and for medicolegal civil matters, accurate percent stenosis is often important to determine. There are three factors limiting accuracy in this regard: lack of perfusion fixation, subsequent tissue shrinkage during fixation and processing, and use of reference segment to determine percent narrowing.

Firstly, if the arteries are not perfusion fixed, then medial collapse of an uninvolved quadrant of the vessel can greatly overestimate percent stenosis, as the lumen is artifactually compromised. This artifact is greatest in eccentric plaques and those with mild to moderate stenosis; indeed, a 25% lesion could be seen as >90% if the vessel is collapsed.

The second source of error is tissue shrinkage. In reality, because of differential shrinkage of intimal tissues versus smooth muscle wall, the affect on percent stenosis is minimal. For segments with about 50% stenosis before processing, there is an increase to about 65% after processing. However, for 80% stenosis, there is actually a decrease in percent stenosis after processing to almost 70%.

8Thirdly, angiographic assessment of coronary narrowing is performed comparing the culprit segment with a proximal, presumably normal, segment. At autopsy, the assessment of coronary narrowing is performed comparing the intimal area to the area within the internal elastic lamina at the same segment. Therefore, affects of positive remodeling are not taken into account; therefore, the degree of stenosis is further exaggerated compared to angiographic methods.

Pathologic Staging of Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerotic plaques enlarge over time, resulting in progressive luminal narrowing. In reality, the decrease in lumen is not linear, because of episodic thrombi that suddenly enlarge the plaque. Also, the narrowing is not directly depending on plaque area, because compensatory remodeling expands the wall and counteracts the decrease in luminal area.

The American Heart Association has adopted a scheme of plaque stages denoted by Roman numerals (

Table 150.1).

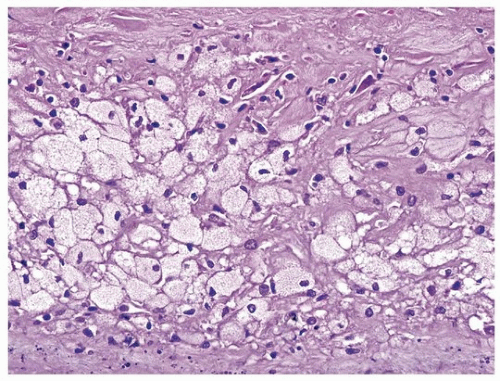

9 Some of the terms have been adopted from aortic lesions that were traditionally staged by gross inspection and after staining with lipophilic substances such as oil red O. A type I plaque is a fibromuscular intimal lesion without significant lipids. A type II plaque has intimal foam cells (predominantly macrophages), and a type III plaque has extracellular lipid, primarily esterified, with little free cholesterol (

Fig. 150.3). The type III plaques are sometimes referred to as preatheroma. Type II and III lesions are not distinct and occur simultaneously as plaques progress

10 (

Figs. 150.3 and

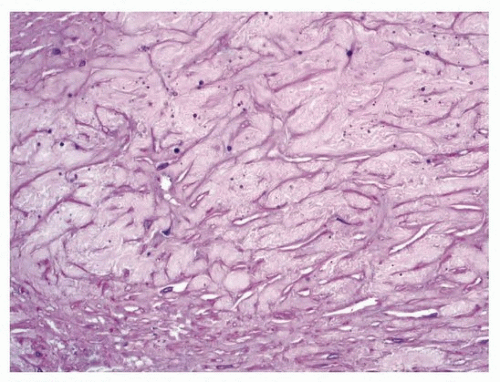

150.4). The lipids are of two types, cholesterol and triglycerides, reflecting the low-density lipoprotein particles, which enter preferentially if oxidized. Stage IV plaques have a necrotic core, which is richer in free cholesterol and fatty acids, reflecting apoptotic breakdown of smooth muscle cells and macrophages (

Fig. 150.5). Stage V plaques have a thick cap, which is frequently calcified, and stage VI plaques show hemorrhage, surface disruption, or thrombus (

Fig. 150.6).

The traditional numerical classification does not identify the so-called thin-cap fibroatheroma, an important form of “vulnerable” plaque, or one prone to thrombosis.

11 Also, plaques with multiple

necrotic cores are frequently the result of healed plaque ruptures, so the numerical classification does not accurately reflect chronology of plaque progression.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access