Chapter 3

Coronary Artery Disease and Acute Coronary Syndrome

Asif Adnan1 and David Adlam2

1Royal Derby Hospital, UK

2Department of cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, UK

Epidemiology

The global burden of coronary disease is still rising. In the United Kingdom, ischaemic heart disease remains the most common cause of mortality among men and women, accounting for approximately 64 000 deaths in the year 2012. This translates to around 1 in 6 deaths in men and 1 in 10 deaths in women. However, a better understanding and control of risk factors (primary prevention) along with advancement in treatment strategies has nearly halved death rates over the past 10 years (Office of National Statistics, United Kingdom).

Pathophysiology

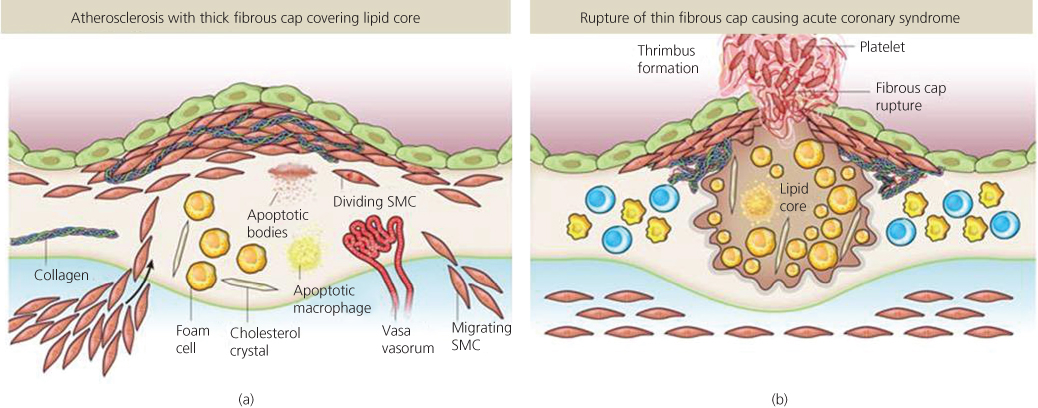

Clinically, coronary artery disease presents either acutely with myocardial infarction (MI) or chronically with stable angina. Stable angina occurs when progressive coronary stenosis leads to an insufficiency of myocardial blood supply, particularly at times of increased myocardial metabolic demand, such as on exercise. This leads to myocardial ischaemia and symptomatic angina (Figure 3.1a). MI results from acute occlusive thrombus formation at the site of an atherosclerotic plaque leading to myocardial ischaemia or infarction. This frequently results from a disruption at sites where the fibrous cap overlying atherosclerotic plaque is thinned. This exposes prothrombotic elements of the necrotic core to the flowing coronary blood triggering platelet activation aggregation and subsequent thrombus formation (Figure 3.1b). Over time, areas of atherosclerosis become increasingly calcified.

Figure 3.1 Types of atherosclerotic plaque. (a) Atherosclerotic plaques with thicker fibrous caps are less likely to rupture but may lead to coronary stenosis restricting coronary blood flow and causing stable angina when myocardial oxygen demand is high. (b) Atherosclerotic plaques with a large necrotic core and thin fibrous cap are vulnerable to rupture triggering platelet activation and thrombus formation leading to an acute coronary syndrome. Source: Adapted from Libby et al. (2011). Reproduced by permission of Nature Publishing Group.

Risk factors

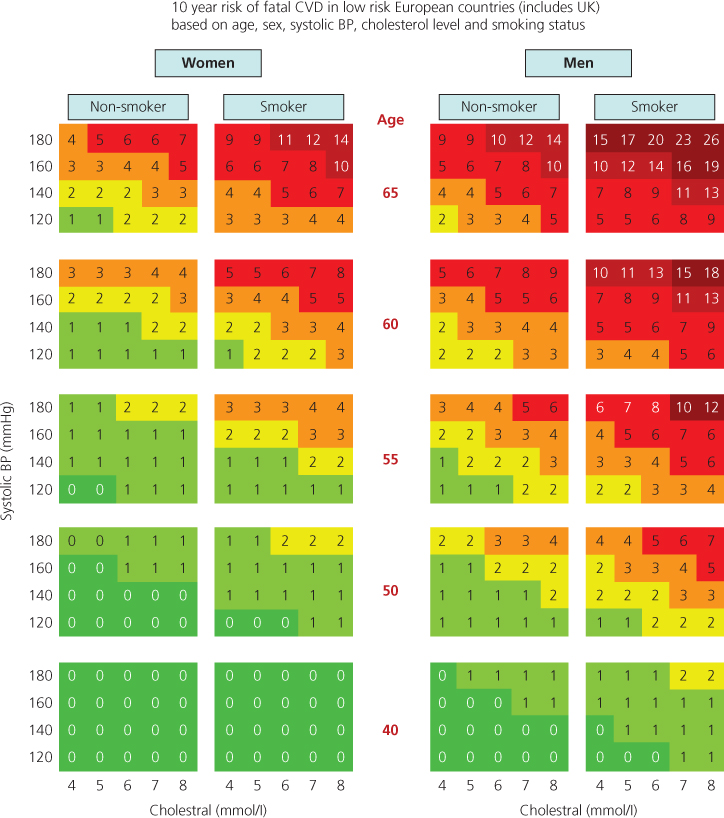

The non-modifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease are advanced age, male sex and family history. The modifiable risks are tobacco smoking, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, truncal obesity, dietary habits, alcohol consumption and physical activity. Together these account for >90% of the risk of an MI. Understanding of the role of genetic factors in determining risk may become an important element of patient risk profiling. The risk of a cardiovascular event can be estimated using calculations derived from previous population studies (example shown in Figure 3.2)

Figure 3.2 Example of a risk calculator for determining patient risk on the basis of common risk factors. A cell is identified for a given patient based on age, sex, systolic BP, cholesterol level and smoking status. This gives the percentage risk over 10 years. Risk is higher than estimated in patients with obesity, sedentary life style, family history of premature CVD, ethnic minority with poorer socioeconomic background, chronic kidney disease, low HDL (high-density lipoprotein) and high triglycerides. Source: Adapted from Conroy et al. (2003). Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press.

Management of risk factors

For both primary and secondary prevention of coronary disease, patients should be given advice and support for smoking cessation, better dietary habits and an active life style. Hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes should be treated with the aim of achieving therapeutic targets (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Therapeutic targets for common risk factors for subjects at high risk of coronary artery disease.

| Risk factor | Ideal target |

| Hypertension | |

| Diabetic | 130/80 mmHg |

| Non-diabetic | 140/85 mmHg |

| Diabetes | HBA1c < 6.5% |

| Hyperlipidaemia | |

| Total cholesterol | <4 mmol/L or >25% reduction |

| LDL | <2 mmol/L or >30% reduction |

This includes patients with established atherosclerotic disease, asymptomatic individuals with estimated CVD (cardiovascular disease) risk of ≥ 20% over 10 years and any patient with diabetes.

Chronic stable angina

History

The classical description of ‘Angina Pectoris’ is of a constrictive retrosternal pain with or without radiation to the arm or jaw that comes on exertion and relieves with rest or sublingual nitrate. However, chest pain is a common presenting symptom (2.5–3% of all emergency room attendance) and there is considerable variation in patients’ description of angina. A low index of suspicion is therefore required. Some patients present without chest pain describing only exertional breathlessness, a condition termed ‘angina equivalent’. The key element of the history is usually a limitation of exercise capacity due to chest discomfort and/or breathlessness (although even this may be difficult to gauge in

patients with poor mobility). The clinical pretest probability can be further enhanced by a detailed assessment of risk factors. This will then guide decision making on treatment including therapeutic risk factor modification and further investigations with a view to potential coronary revascularisation.

Physical examination

A patient with angina often will have no abnormality on physical examination. But features of risk factors such as nicotine staining, xanthelasma, hypertension and signs of end organ damage from diabetes may be present. Cardiovascular examination might reveal signs of heart failure, valvular disease or peripheral vascular disease.

Investigation

Simple investigations such as blood pressure, blood sugar and cholesterol and urine dip stick are invaluable in detecting otherwise unknown risk factors.

A resting 12-lead electrocardiograph (ECG) should be performed. This may show markers of hypertension (e.g. signs of left ventricular hypertrophy), evidence of old MI (e.g. pathological Q waves). A normal ECG does not exclude clinically important coronary artery disease.

Table 3.2 Investigating stable chest pain.

| Clinical assessment | First-line diagnostic test |

| Features of typical angina and estimated likelihood of CAD >90%* | None required, manage as angina |

| Stable angina cannot be excluded on clinical assessment alone and | |

| Estimated likelihood of CAD is 61–90%* | Invasive coronary angiography |

| Estimated likelihood of CAD is 30–60%* | Non-invasive functional imaging (e.g. MPS, cardiac stress MRI and stress echo) |

| Estimated likelihood of CAD is 10–29%* | CT calcium scoring |

* See NICE clinical guideline 95 (CG95 March 2010); MPS, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy.

A chest radiograph may show cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion and will assess the non-cardiac structures for other potential explanation of the symptoms.

The next stage of investigation is aimed at confirming diagnosis and deciding whether or not to proceed to coronary angiography. The choice of investigation depends on the clinical pretest probability. The mainstay of investigation until recently was the exercise ECG. Although this test is still widely used, it is limited by relatively low specificity and sensitivity in the setting of diagnosing angina. The gold standard anatomical test for coronary artery disease is angiography; this is an invasive procedure and is associated with a small procedural risk. In patients with a very high pretest probability, it remains appropriate to proceed directly to angiography. However, in those with intermediate pretest probabilities, a number of non-invasive tests have been developed to determine which patients should proceed to angiography. These can be divided into anatomical tests such as computed tomography (CT) coronary calcium scoring and CT angiography that is most effective at discriminating those at the lower end of pretest risk and functional tests such as stress echocardiography, stress magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and myocardial perfusion scintography that are most effective in those with intermediate pretest risk (Figure 3.3). The relative role of each imaging modality in the diagnosis of stable coronary disease remains subject to ongoing research and the current UK NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Effectiveness) recommended strategy is summarised in Table 3.2. A summary of the overall approach is presented in Box 3.1.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree