Chapter 21

Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery

1. What are the indications for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)?

2. How does CABG compare with medical management for CAD?

3. How does CABG compare with stents?

4. What about with drug-eluting stents (DES)?

Drug-eluting stents have reduced the problem of restenosis, but data directly comparing DES with CABG is limited and still relatively short-term. In a registry study from the New York state cardiovascular database, CABG resulted in improved survival at 3 years compared with DES for patients with double- and triple-vessel disease. ARTS II randomized patients to DES or CABG, and showed that the primary composite outcomes at one year were similar. The international SYNTAX trial, involving 85 centers and 1800 patients with multivessel or left main CAD, recently published 3-year follow-up data in 2011. This showed worse outcomes in the PCI group as compared to the CABG group at 3 years, with increased composite major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE: death, stroke, MI, or repeat revascularization). Although there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality and stroke at 3 years, MI and repeat revascularization were both increased in the PCI group. The study concluded that patients with more complex disease (three-vessel CAD with intermediate-high SYNTAX scores and LM artery CAD with high SYNTAX scores) have an increased risk of MACCE with PCI, and CABG is the preferred treatment option.

6. Which patients benefit most from CABG?

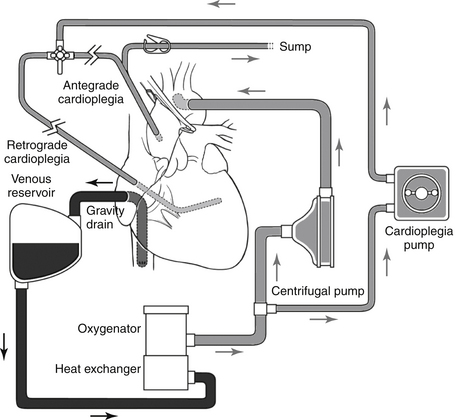

7. What is the cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) pump, and how is it used?

8. Why is heparin required for CPB?

9. How is the heart stopped while on CPB?

The heart is stopped by placing a completely occluding cross-clamp across the ascending aorta, below the aortic cannula, eliminating arterial blood flow to the coronary arteries. Cardioplegia solution is then used to induce arrest of the heart, and can be given antegrade and/or retrograde. Components of cardioplegia solution are varied in different institutions but include potassium to achieve diastolic arrest. Cardioplegia solution administered into the aortic root, via a small cannula below the cross-clamp, is delivered in an antegrade fashion to the myocardium via the coronary ostia. Retrograde cardioplegia is also used frequently, by infusing cardioplegia solution into the coronary sinus with backward filling of the cardiac veins to reach the myocardium, and is especially important in situations where antegrade may not be as effective, such as with severe CAD and aortic valve insufficiency. Most commonly, cold cardioplegia at 4° C is administered intermittently in 15- to 20-minute intervals. Blood can be mixed to the crystalloid component of cardioplegia in a 4:1 mix to provide oxygenated blood to the myocardium and to buffer the pH of the tissue (Fig. 21-1).