Chapter 53 Connective Tissue Diseases

Epidemiology

Specific CTDs include the following:

• Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common CTD and occurs worldwide in approximately 1% of the adult population.

• Systemic sclerosis (SSc) has a prevalence of approximately 10 in 100,000 population, with a female/male ratio of 4 : 1 to 9 : 1.

• Polymyositis/dermatomyositis (PM/DM) is relatively rare, affecting 2 to 10 per 1 million people; has a bimodal age distribution, with an early peak at 5 to 15 years and a later peak at 50 to 60; and occurs three to four times more often in women.

• Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) has a prevalence that has not been precisely defined but probably approximates 1 in 10,000 people. Mixed disease is more common in women, and most patients present in the second or third decade of life.

• Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) occurs in up to 1 in 2000 individuals, with a female/male ratio of 10 : 1.

• Sjögren syndrome (SS) has a prevalence of 0.5% to 1% in the general population for primary SS and of 10% to 30% in patients with other autoimmune disorders (secondary SS). SS predominantly affects middle-aged women.

Other CTDs include relapsing polychondritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

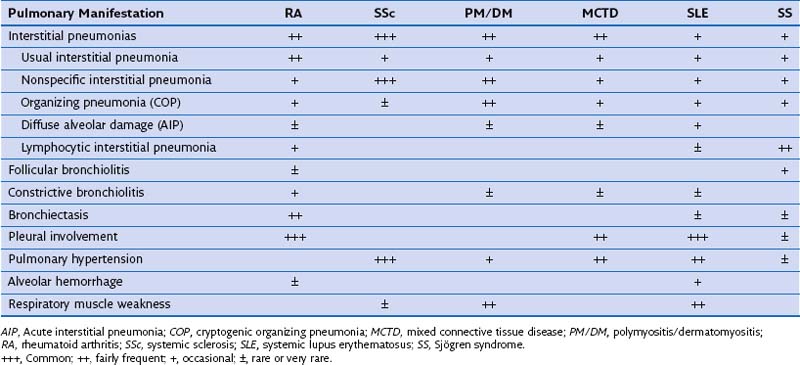

Pulmonary Involvement

Systemic sclerosis shows the highest prevalence of interstitial pneumonia (IP) (±80% nonspecific) and vascular disease among the CTDs. Autopsy studies indicate that at least some degree of pulmonary fibrosis is present in up to 75% of SSc patients, and vascular disease occurs in approximately 30%. RA and PM/DM also show relatively high prevalence of certain degrees of lung fibrosis, but clinically overt disease occurs less often and is similar to SSc (~5%). Compared with SSc patients, those with RA or PM/DM complicated by lung fibrosis show higher frequency of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) and organizing pneumonia (OP). Of all pulmonary manifestations in CTDs, pleural disease is probably the most common, especially in RA and SLE. Table 53-1 summarizes the relative frequencies of the major respiratory complications, including IP subtypes, across the various CTDs.

Lung Pathology

Airway Pathology

Obliterative Bronchiolitis

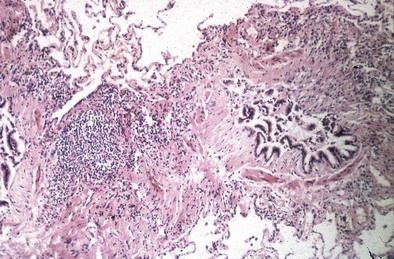

Obliterative bronchiolitis (OB) is thought to begin with damage of the respiratory epithelium of terminal bronchioles, leading to the formation of chronic inflammatory granulation tissue, often laid down in a circumferential pattern causing narrowing of the airways. Disease progression leads to obliteration of terminal bronchioles by dense fibrous tissue, with sparing of the respiratory bronchioles and alveoli (Figure 53-1).

Figure 53-1 Lung biopsy of patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), showing constrictive bronchiolitis.

Parenchymal Pathology

Interstitial Pneumonias

Both DIP and RBILD are strongly associated with smoking and might not belong in the “idiopathic” IP classification system. Moreover, only small numbers of patients with histologic patterns of DIP and RBILD have been reported in series relating to CTDs, and many of these were smokers. Therefore, these two IP entities are unlikely to be causally related to CTD. Table 53-2 summarizes the histopathologic characteristics of the IPs typically seen in CTDs.

Table 53-2 Interstitial Pneumonias in Connective Tissue Disease: Major Histopathologic Characteristics

| Type | Histopathologic Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) | Fibrosis with honeycombing, fibroblast foci; anatomic destruction; little inflammatory cell infiltrate; normal/near-normal intervening lung parenchyma (temporal heterogeneity) |

| Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) | Variable interstitial inflammation and fibrosis; fibroblastic foci absent or scarce; uniformity of changes within biopsy specimen |

| Organizing pneumonia (OP; or cryptogenic OP) | Patchy filling of alveoli by buds of granulation tissue that may extend into bronchioles (Masson bodies); preservation of lung architecture |

| Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) | Extensive lymphocytic infiltration in the interstitium often associated with peribronchiolar lymphoid follicles (follicular bronchiolitis) |

| Diffuse alveolar damage (DAD)* | Diffuse alveolar septal thickening by inflammatory cell infiltrate, hyperplastic pneumocytes, hyaline membranes, air space organization |

Clinical Features

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Airways Disease

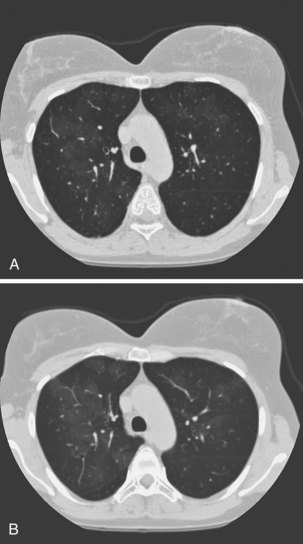

Obliterative bronchiolitis is a serious complication of RA, and seems to be more common in women. OB usually occurs in patients who are RF positive and have well-established joint disease. In the past, penicillamine, which is rarely used now, was associated with development of OB in patients with RA. Also, a relationship with gold therapy has been suggested. Patients most often are initially seen with dyspnea and a nonproductive cough, which can worsen rapidly. The chest radiograph is usually normal but may show signs of hyperinflation (Figure 53-2) and in later stages fibrobullous degeneration (Figure 53-3). The diagnosis of OB should be considered in any patient with RA with progressive dyspnea and cough who has rapidly progressive airflow obstruction. Characteristic HRCT findings of OB consist of areas of decreased attenuation and vascularity with blood flow redistribution, resulting in areas of increased lung attenuation and vascularity (“mosaic perfusion” pattern), which is accentuated on expiratory scans (Figure 53-4). The prognosis is poor in RA patients with OB.

Figure 53-3 Chest radiograph of same patient as in Figure 53-2 a few years later, showing evolution toward fibrosis and bullous degeneration.

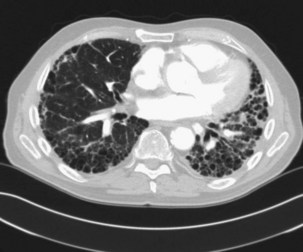

Interstitial Pneumonias

The prevalence of clinically significant IP in patients with RA is estimated at 5%. IP is seen more often in men than in women, especially in the context of a high RF titer and severe articular disease. The pathologic patterns are diverse, but in contrast to other CTDs, a UIP pattern is relatively common (Figure 53-5). Symptoms are nonspecific and include progressive dyspnea and nonproductive cough. Dyspnea may appear late because of physical inactivity secondary to polyarthritis. Most patients have fine bibasilar crackles, but digital clubbing is less common than in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Lung function tests usually reveal a restrictive defect with normal airflow and reduced diffusion capacity (DLCO). HRCT is the most appropriate investigation to detect IP and is also useful in follow-up. UIP patterns on HRCT appear similar in RA and IPF, but coexisting pleural effusion or (necrobiotic) nodules may help in the differential diagnosis. In general, UIP associated with RA tends to follow a more benign course than the idiopathic form, but patients may develop end-stage respiratory failure (Figure 53-6).