Complete versus Incomplete Revascularization

Jeffrey C. Trost

Daniel L. Dries

Bernard J. Gersh

Patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD) have several therapeutic options to ameliorate the signs and symptoms of ischemia. These include medical therapy, revascularization via percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and/or stenting, and revascularization via coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). Certain subsets of patients with multivessel CAD, such as those with left main CAD, depressed ventricular function, and proximal left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery disease, live longer and experience less angina with surgical revascularization than similar patients treated with medical therapy alone. The primary explanation for these improved outcomes with surgery has been seemingly straightforward. Bypassing diseased coronary arteries with arterial and/or venous conduits achieves “complete” revascularization. By restoring normal blood flow to areas of previously ischemic and dysfunctional myocardium, bypass surgery facilitates improvement in left ventricular function and symptoms of ischemia.

In contrast, percutaneous revascularization in its incipient stage was limited to focal, discrete, and proximal coronary arterial stenoses. As a result, interventionalists could not offer “complete” revascularization in most patients with multivessel CAD. However, in the last two decades, advances in percutaneous techniques and new device technologies have enabled the interventional cardiologist to treat increasingly complex, as well as multiple, coronary arterial stenoses. Consequently, in many patients with multivessel CAD, contemporary percutaneous therapy may offer “complete” revascularization that is anatomically equivalent to bypass surgery, thus offering the potential of equivalent outcomes for patients who receive either therapy.

For a variety of reasons that will be explored in this chapter, not all patients who undergo percutaneous or surgical revascularization will receive “complete” revascularization. In fact, in some patients, “incomplete” revascularization may be a preferred percutaneous strategy. In this chapter, we explore the definitions of complete and incomplete revascularization, review the theoretical strengths and limitations of both strategies, and examine the clinical outcomes of patients who receive them.

COMPLETE AND INCOMPLETE REVASCULARIZATION: DEFINITIONS

A precise definition of what constitutes “complete” revascularization is difficult. The most common definition—surgical bypass or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of all coronary arteries with at least one angiographically significant stenosis—has multiple shortcomings. First, within a single study, lesion assessment by angiography is subject to significant interobserver variability, which could lead to variability in the actual degree of revascularization that patients receive, or variability in the retrospective classification of patients as “completely” or “incompletely” revascularized. In short, this could “blur” the line that differentiates these groups of patients,

increasing the likelihood that no differences in outcomes will be found among both groups, even if a difference may exist. To reduce the likelihood of significant interobserver variability, most studies use a central or “core” angiographic laboratory for the interpretation and classification of patient angiograms.

increasing the likelihood that no differences in outcomes will be found among both groups, even if a difference may exist. To reduce the likelihood of significant interobserver variability, most studies use a central or “core” angiographic laboratory for the interpretation and classification of patient angiograms.

In addition to interobserver variability of angiographic assessment within studies, interstudy variability exists with regard to what constitutes an angiographically significant coronary arterial stenosis. Early surgical and PCI studies defined a coronary arterial stenosis of >50% in a vessel of ≥1.5 mm in diameter as angiographically significant; however, more recent authors have used 60% or 70% as a cutoff for a significant stenosis. Therefore, it is difficult to compare outcomes among studies using different angiographic definitions of complete revascularization.

Finally, using angiographic criteria to define complete revascularization fails to account for the physiologic, or functional, significance of the angiographic stenosis(es). In many studies, an occluded coronary artery is classified as angiographically significant and would require revascularization in order to be labeled “complete.” However, this same artery may be supplying dead, nonfunctional myocardium, thus raising the question: What benefits are derived from revascularizing anatomically significant but functionally insignificant coronary arterial lesions? To address this question, Faxon et al. characterized the functional status of revascularization in a series of 67 patients with incomplete PCI (1). Functionally adequate revascularization was defined as the successful dilatation of all 70% stenoses in bypassable vessels serving viable myocardium. Myocardium was deemed nonviable if akinetic by left ventricular angiography or nonfunctional if supplied by a vessel too small to undergo bypass surgery (<1.5 mm in diameter). The combined rate of death, myocardial infarction (MI), or need for CABG was significantly lower in patients with functionally adequate revascularization than in patients with functionally inadequate revascularization (6% versus 27%). In addition, patient outcomes of the functionally adequate group were similar to the outcomes of patients who underwent complete anatomic percutaneous revascularization.

For the purposes of this chapter, complete percutaneous revascularization is defined as the achievement of no residual stenosis of ≥50% in all significantly (>70%) stenosed vessels of ≥1.5 mm in diameter. Therefore, incomplete revascularization is the converse of this definition: namely, the presence of a residual stenosis of >50% in at least one vessel of ≥1.5 mm in diameter following PCI. Complete surgical revascularization is defined as bypass grafting of all coronary arteries with at least one angiographically significant (>70%) stenosis, whereas incomplete surgical revascularization represents the failure to graft at least one stenosed or occluded coronary artery.

POTENTIAL STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF COMPLETE VERSUS INCOMPLETE REVASCULARIZATION

The strategy of complete revascularization has several clear advantages in patients with multivessel CAD. By providing complete restoration of blood flow to all major areas of myocardium, complete revascularization may improve global left ventricular function in patients with recently ischemic, or stunned, myocardium as well as in patients with chronically ischemic, or hibernating, myocardium. Complete restoration of blood flow may also provide both optimal relief from anginal symptoms, as well as optimal protection against life-threatening, ischemic-related dysrhythmias. Therefore, complete revascularization often is the intended goal of the surgeon and the interventional cardiologist in the therapeutic approach to the patient with multivessel CAD.

Despite these advantages, complete revascularization cannot be accomplished in all patients. Surgical limitations include: (a) the inability to bypass arteries that are < 1.5 mm in size; (b) the inability to bypass diffusely diseased vessels (which can be underestimated angiographically); (c) the presence of severe comorbidities, such as advanced age, renal failure, and extensive peripheral vascular disease, which place patients at high risk of surgery-related complications and mortality; (d) the presence of a calcified, or “porcelain” aorta, which precludes cardiopulmonary bypass; and (e) the presence of poor arterial or venous conduits for bypass. Percutaneous limitations include: (a) the inability to dilate lesions in vessels < 1.5 mm in size; (b) the inability to successfully dilate complex lesions, such as chronic total occlusions, ostial lesions, bifurcation lesions, and diffusely diseased vessels; and (c) the presence of comorbidities, such as severe left ventricular dysfunction, severe valvular disease, severe peripheral vascular disease, and a bleeding diathesis, which would place patients at high risk of PCI-related complications and mortality.

Surgeons and many interventional cardiologists who pursue an intended strategy of complete revascularization may confront these limitations and ultimately provide an unintentional result of incomplete revascularization. Alternatively, both surgeons and interventional cardiologists, depending on the clinical scenario, may pursue an intentional strategy of incomplete revascularization, in which they attempt to identify and treat a “culprit” lesion— the lesion contributing to the patient’s symptoms—in the setting of multivessel disease, leaving the non-“culprit” lesions untreated. For example, in the setting of an acute ST-elevation MI (STEMI), multivessel disease may be discovered during the diagnostic catheterization, but only the infarct-related artery and its corresponding lesion are treated. If the patient has recurrent symptoms following PCI, or objective evidence of ischemia at a later date, other diseased vessels are considered for percutaneous therapy.

This strategy also can be extended to patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation who undergo diagnostic catheterization, as well as to patients with chronic stable angina. In addition, an intentional strategy of surgical incomplete revascularization may be pursued in patients ineligible for percutaneous therapy and considered high-risk for surgical complications. In this scenario, the surgeon may perform a minimally invasive or “off-pump” coronary artery bypass surgery, which most commonly allows bypass of the LAD coronary artery and its branches without the need for cardiopulmonary bypass.

This strategy also can be extended to patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation who undergo diagnostic catheterization, as well as to patients with chronic stable angina. In addition, an intentional strategy of surgical incomplete revascularization may be pursued in patients ineligible for percutaneous therapy and considered high-risk for surgical complications. In this scenario, the surgeon may perform a minimally invasive or “off-pump” coronary artery bypass surgery, which most commonly allows bypass of the LAD coronary artery and its branches without the need for cardiopulmonary bypass.

TABLE 39.1. STUDIES IDENTIFYING CULPRIT LESIONS | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The major advantage of intended incomplete revascularization is that it exposes the patient to a lower risk of procedural-related complications. Only the culprit lesion is treated, and therefore, the accompanying risks of coronary arterial perforation, dissection, and need for emergent bypass surgery are limited to this lesion. By comparison, these risks would be additive if multiple lesions are treated in a complete revascularization strategy. In addition, utilization of potentially nephrotoxic contrast dye as well as radiation exposure for the patient and operator is minimized in the treatment only of a culprit lesion.

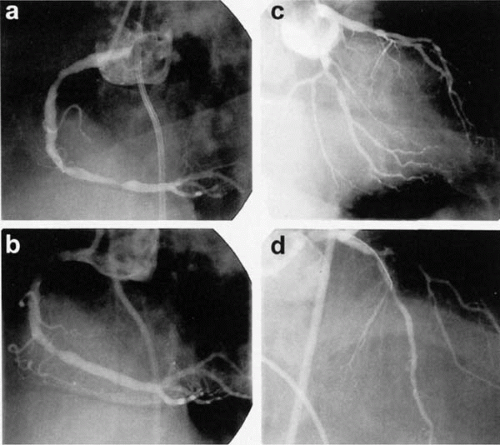

Unfortunately, identifying the culprit lesion in multivessel disease is often challenging and inaccurate. Several studies have shown that, in the setting of unstable angina, an angiographic evaluation, alone or in combination with electrocardiographic evidence of ischemia, identifies a culprit lesion in 21% to 75% of angiograms (Table 39.1) (2, 3, 4, 5). In the setting of chronic stable angina and multivessel disease, an angiographic evaluation often reveals multiple, significant stenoses, and it is entirely possible that one, several, or all of these lesions may be producing the patient’s symptoms. Noninvasive perfusion imaging and physiologic lesion assessment using intracoronary Doppler flow have been proposed to help direct percutaneous intervention towards potential culprit lesions (Fig. 39.1), and evidence to support these approaches is reviewed in Section II of this book.

In patients with acute coronary syndromes, recent biochemical and angiographic data suggest the presence of widespread coronary inflammation, rather than a single culprit lesion. In patients with unstable angina, Buffon et al. identified widespread neutrophil activation across the coronary vascular bed, regardless of the location of the culprit stenosis. The same phenomenon was not seen in patients with chronic stable angina, variant angina, and patients without coronary disease (7). In addition, the presence of multiple complex angiographic plaques has been shown to be a predictor of recurrent coronary events and the need for revascularization. Goldstein et al. reviewed angiograms of 253 patients with acute MI, and stratified them by the presence of single or multiple complex plaques. At 1 year following their index MI, patients with multiple plaques were significantly more likely to have recurrent acute coronary syndromes and require angioplasty (particularly in nonindex infarct-related arteries) and/or CABG surgery (8). Therefore, it may be more accurate to view patients with acute coronary syndromes as having an acute, diffuse inflammatory vascular disease, rather than a focal “culprit.” If one accepts this viewpoint, the specific target(s) for revascularization therapy becomes less clear.

OUTCOMES OF SURGICAL PATIENTS TREATED WITH COMPLETE VERSUS INCOMPLETE REVASCULARIZATION

For cardiothoracic surgeons, complete revascularization using CABG surgery is the primary goal, and a strategy of incomplete revascularization is rarely intentional. Therefore, prospective, randomized comparisons of these two revascularization strategies do not exist in the surgical literature. Consequently, the best available evidence for comparison of outcomes consists of nonrandomized series of surgical patients, which requires adjustment of outcomes to account for baseline differences among patient groups. Because patients with incomplete revascularization tend to be sicker than patients who receive complete revascularization, this is an important consideration in analyzing the comparative results of each study.

The incidence of CABG patients who actually receive complete revascularization varies among surgical series. In the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) registry, in which 3,372 nonrandomized patients with three-vessel coronary artery disease underwent bypass surgery, 66% of patients (n = 2,240) received complete revascularization (6), and smaller surgical series have reported rates of >80% (9,10). With regard to patient outcomes, the two largest surgical series that compare patients with complete versus incomplete revascularization are the CASS registry and a series reported by Jones et al. (2,860 patients) (6,9). The CASS registry required the enrollment of patients with three-vessel disease and required bypass of all angiographic stenoses of >70% in bypassable vessels for complete revascularization. In contrast, Jones et al. included patients with two-vessel and three-vessel CAD and used a stenosis cutoff of >50%.

In the CASS registry, patients with incomplete revascularization (n = 1,132) were more likely to have a history of prior MI or congestive heart failure (CHF), a higher myocardial jeopardy score, and a lower ejection fraction at baseline. After adjustment for baseline differences, freedom from death, MI, reoperation, or development of angina at 6 years was found to be significantly higher in patients who received complete revascularization (69% versus 45% in the incompletely revascularized group, p = 0.04) if they had severe preoperative angina (CCS Class III or IV) and a preoperative ejection fraction of <0.35. This difference was driven primarily by the development of recurrent angina in patients with incomplete revascularization. In patients with mild preoperative angina and/or normal preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction, there were no significant differences in the composite endpoint.

In the study by Jones et al., patients were followed up to 12 years after their initial surgery. As in the CASS registry, patients who received incomplete revascularization (n = 803) were more likely to have a prior history of MI and worse left ventricular dysfunction. No significant differences were found among completely and incompletely revascularized patients with respect to perioperative complications, in-hospital death rate, and length of hospital stay. At 12-year follow-up, patients with incomplete revascularization had a significantly higher prevalence of recurrent angina. Unlike the CASS registry, Jones et al. found a significant difference in overall survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis, favoring patients with complete revascularization, appearing in year 1 (98% versus 96% for incompletely revascularized patients) and peaking at year 9 (81% versus 72%), with merging of Kaplan-Meier survival curves by year 12. The discrepancy in survival outcomes between the CASS registry and the series by Jones et al. cannot be explained easily; both groups of patients received their initial CABG within the same time frame and their baseline characteristics were similar. Although the Jones study had longer follow-up (12 versus 6 years), the survival benefit was apparent by year 1, in contrast to the CASS registry, in which no significant survival benefit was seen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree