As few studies have reported the impact of transradial interventions (TRIs) versus transfemoral interventions (TFIs) on percutaneous coronary interventions using real-world registry data, we compared the clinical and procedural outcomes between TRIs and TFIs in the Korean Transradial Intervention Prospective Registry. Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions were consecutively registered from February 2014 to July 2014 in this multicenter registry. Composite events were evaluated for all-cause deaths, nonfatal myocardial infarctions, and repeat revascularizations within 30 days. Nonlesion complications included access site complications and bleeding events. A total of 1,225 patients (232 for TFIs and 993 for TRIs) were analyzed. All-cause deaths and composite events were more frequent in the TFI group than in the TRI group. Procedure failures and nonlesion complications were also more frequent in the TFI group, whereas lesion complication rates were similar in the 2 groups. Procedure times were not different between the 2 groups, whereas fluoroscopy times were longer and contrast volumes were larger in the TFI group. However, in a propensity score-matched cohort, all-cause deaths, composite events, procedure failures, and lesion and nonlesion complications were not different between the 2 groups. In contrast, in the matched cohort, the procedure and fluoroscopy times were longer and the contrast volumes were larger in the TFI group. In conclusion, TRI was as effective and safe as TFI in terms of short-term clinical outcomes, procedure success rates, and complication rates, whereas TRI was more effective for reducing procedure times and hazardous exposure to radiation and contrast media.

The transradial approach has been increasingly used for percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs). Although transradial interventions (TRIs) require a certain training period for operators to learn their delicate techniques, they have advantages over transfemoral interventions (TFIs), such as easier bleeding control and earlier ambulation after PCI. Reflecting these advantages, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have shown that TRI can reduce vascular complications and improve clinical outcomes, compared with those of TFI. Consequently, TRIs are now considered as the primary approach in many coronary intervention centers. However, there have been few studies comparing TRI and TFI using real-world registry data. Patient characteristics in RCTs may be different from those in real-world practices, where PCI access routes are decided by the patients’ given conditions such as clinical diagnosis, underlying diseases, body size, and bleeding tendency. Therefore, analyses of real-world registry data may convey important information about the effect of TRI in actual clinical practice. Short-term clinical outcomes of PCIs are strongly associated with procedural outcomes, including coronary perfusion, access site vascular damage, and bleeding complications. In addition, procedure times, fluoroscopy times, and the amounts of contrast media are also related to clinical outcomes, radiation hazards, and kidney injuries after PCI. Therefore, we investigated clinical outcomes, complication rates, procedure times, fluoroscopy times, and contrast media volumes using a multicenter registry data set and compared the results between patients undergoing TRIs and those undergoing TFIs.

Methods

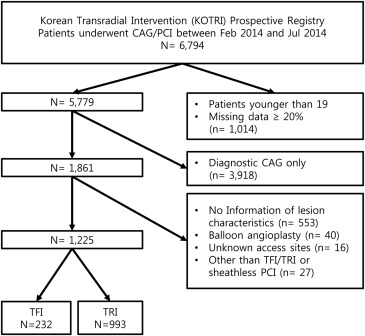

The Korean Transradial Intervention (KOTRI) prospective registry was a nation-wide registry in which 122 operators from 20 tertiary PCI centers participated. TRIs were preferentially performed in all centers. Patients who had undergone coronary angiography or PCI at the participating centers between February 2014 and July 2014 were consecutively enrolled in the registry. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before they enrolled in the registry. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers. Patients aged older than 18 years who underwent PCI at one of the 11 centers where information regarding coronary lesion characteristics was reported were included. Patients whose case report forms were missing ≥20% of data, whose access sites were unknown, or who had undergone balloon angioplasty only or PCIs using approaches other than a femoral and radial approach were excluded. Demographic information, medical and social histories, and laboratory data were obtained from all patients. All patients received 300 mg of aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors (600 mg of clopidogrel, 60 mg of prasugrel, or 180 mg of ticagrelor) before the index procedures, and they received dual-antiplatelet agent therapy for at least 6 months after the index procedures. Detail methods for obtaining laboratory data and the definition of estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and clinical events, including all-cause death, myocardial infarction (MI), and repeat revascularization, are described in the Supplementary Material .

Standardized definitions of clinical events were used as previously described by Hicks et al. An access site crossover was defined as a change in the guiding catheter access site from either the femoral or radial site to the other site during the procedure. Obtaining an additional access route for a bilateral contrast media injection during PCIs for chronic total occlusion (CTO) lesions was not considered a crossover. A composite event was defined as the combination of repeated revascularization, nonfatal MI, and death. The first clinical event that occurred after the index PCI was used as the composite event. A procedure failure was defined as a failure to achieve a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow grade 3 or a remaining luminal narrowing ≥30% after stent implantation at any target coronary lesion. Lesion complications included slow coronary flow after stent implantation, jailed side branches ≥1.5 mm by main artery stents, thrombus formation in coronary arteries or distal embolization of thrombi during PCI, migration of stents, and dissection and/or perforation of coronary arteries. Nonlesion complications included access site complications and bleeding events. Assess site complications were defined as vascular complications that occurred in the access vessel including, hematomas (defined as ≥10 cm in TFIs and ≥2 cm in TRIs), dissections, perforations, arteriovenous fistulas, and pseudoaneurysms. Bleeding complications were defined as previously described by Mehran et al. in a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. A major bleeding complication was defined as a bleeding event that required any transfusion (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 3a). Procedure times were measured from the start of the puncture to the removal of the guiding catheters, and fluoroscopy times were measured automatically using fluoroscopes.

Patients were divided into a TRI group and a TFI group. A propensity score-matching with the nearest neighbor method was performed to compare the TFI group with a matched TRI group. Patients with end-stage renal diseases or histories of coronary artery bypass graft surgery for whom TRIs are seldom conducted were excluded before the matching processes. The covariates for the matching process included age; gender; diabetes; hypertension; peripheral artery diseases; current smoking; history of PCI and MI; use of unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, and glycoprotein inhibitor; PCI sheath sizes; indications for PCIs (in 3 categories: primary, urgent, and elective); cardiogenic shock; estimated glomerular filtration rate; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; hemoglobin levels; lipid profiles; the number of coronary arteries narrowed; total stent length; the number of stents; and lesion characteristics. The C-index of the model for the propensity score-matching was 0.860 (95% CI 0.834 to 0.886). The Student t tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables between the 2 groups. Log-rank tests were used to compare the cumulative incidences of death and the composite events, and Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine the similarities of the procedure failure and complication rates between the 2 groups. Multiple logistic regression analyses with backward variable selection processes were performed to identify significant predictors of lesion and nonlesion complications. Multiple linear regression analyses with stepwise variable selection processes were used to estimate the independent effect of TRI on procedure times, fluoroscopy times, and contrast media volumes in the presence of confounders. All statistical analyses were performed using R-3.1.3 for Windows and designated R packages including survival, rms, descr, MatchIt, and visreg. A p <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Of the 6,794 patients who participated in the registry, 1,225 patients were selected ( Figure 1 ). In the 1,225 patients, access site crossovers occurred in 65 patients (5.3%, 7 in TFIs and 58 in TRIs). In the TRI group, reasons for crossovers included operator preference (n = 21), the need for larger catheters (n = 12), approach vessel tortuosity (n = 10), puncture failure (n = 7), spasm (n = 2), access vessel injury (n = 2), and hemodynamic instability (n = 2). In the TFI group, the reasons included approach vessel occlusion (n = 4) and tortuosity (n = 1) and puncture failure (n = 2). The TFI group included 232 patients, and the TRI group included 993 patients. The mean age was 65.9 ± 11.1 years (range 28 to 96) and 378 patients (30.9%) were women. Hypertension, diabetes, and CKD were found in 564 (46.0%), 309 (25.2%), and 239 (19.5%) patients, respectively. ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were diagnosed in 172 patients (14.0%) and 939 patients (76.7%), respectively. Femoral artery closure devices were used for 61 patients (26.3%) in the TFI group.

The clinical and angiographic characteristics of the patients in the entire cohort and the propensity score-matched cohort are described in Table 1 . In the entire cohort, the TFI group presented more complicated co-morbidities. Female gender, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, CKD, end-stage renal disease, histories of MI, PCI, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery, diagnosis of STEMI and ACS, and use of unfractionated heparin and glycoprotein inhibitor were more frequent in the TFI group. Regarding angiographic data, PCI sheath sizes were larger and primary PCI, multivessel CADs, and CTO lesions were more frequent in the TFI group, whereas bifurcation lesions and severely calcified lesions were more frequent in the TRI group. The number of stents, total stent length, and the incidence rates of diffuse lesions, severely tortuous lesions, and left main coronary artery lesions were not different between the 2 groups. Operator experience levels were higher in the TFI group than in the TRI group. Each group in the propensity score-matched cohort contained 215 patients. Because the TRI group was larger than the TFI group, the patients with complex co-morbidities were selected from the TRI group during the matching process. As a result, the proportions of hypertension, diabetes, CKD, ACS, STEMI, cardiogenic shock, and CTO lesions increased in the TRI group after matching. In the matched cohort, the clinical and angiographic characteristics were not significantly different between the TFI group and the TRI group, with the exception of PCI sheath size, which remained larger in the TFI group.

| Variables | Entire Cohort | Propensity Score-Matched Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFI (n = 232) | TRI (n = 993) | p | TFI (n = 215) | TRI (n = 215) | p | |

| Age (year) | 66.8 ± 11.5 | 65.7 ± 11.0 | 0.220 | 66.7 ± 11.6 | 67.7 ± 11.8 | 0.380 |

| Female gender | 86 (37.1%) | 292 (29.4%) | 0.023 | 138 (64.2%) | 133 (61.6%) | 0.617 |

| Hypertension | 126 (54.3%) | 438 (44.1%) | 0.005 | 114 (53.0%) | 121 (56.3%) | 0.468 |

| Diabetes | 84 (36.2%) | 224 (22.6%) | <0.001 | 76 (35.3%) | 76 (35.5%) | 0.681 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 11 (4.7%) | 21 (2.1%) | 0.024 | 11 (5.1%) | 9 (4.2%) | 0.481 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 76 (32.8%) | 162(16.3%) | <0.001 | 64 (29.8%) | 59 (27.4%) | 0.647 |

| End-stage renal disease | 11 (4.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Current smoker | 49 (21.1%) | 276 (27.8%) | 0.038 | 47 (21.9%) | 45 (20.9%) | 0.814 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 36 (15.5%) | 93 (9.4%) | 0.006 | 32 (14.4%) | 30 (14.0%) | 0.890 |

| Prior PCI | 67 (28.9%) | 160 (16.1%) | <0.001 | 55 (26.4%) | 60 (28.8%) | 0.584 |

| Prior CABG | 11 (4.7%) | 1 (0.1%) | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 192 (82.8%) | 747 (75.2%) | 0.015 | 179 (83.3%) | 176 (81.9%) | 0.703 |

| ST segment elevation MI | 61 (26.3%) | 111 (11.2%) | <0.001 | 60 (27.9%) | 49 (22.8%) | 0.253 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 5 (2.2%) | 5 (0.5%) | 0.012 | 5 (2.3%) | 4 (1.9%) | 0.736 |

| Physical and laboratory data | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 129.5 ± 28.4 | 132.3 ± 23.4 | 0.167 | 129.4 ± 28.8 | 128.9 ± 23.8 | 0.842 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.2 ± 14.3 | 75.9 ± 13.1 | <0.001 | 72.0 ± 14.4 | 71.9 ± 13.3 | 0.905 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.8 ± 2.2 | 13.6 ± 1.8 | <0.001 | 12.9 ± 2.2 | 12.9 ± 2.1 | 0.989 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 167.0 ± 43.9 | 176.8 ± 44.6 | 0.003 | 163.7 ± 41.1 | 165.5 ± 43.7 | 0.664 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) ∗ | 111 (77, 156) | 125 (88, 181) | 0.002 | 114 (84, 158) | 110 (72, 155) | 0.445 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 42.1 ± 10.3 | 42.9 ± 11.3 | 0.259 | 40.8 ± 9.1 | 40.9 ± 9.5 | 0.903 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) ∗ | 104 (75, 133) | 108 (82, 135) | 0.211 | 98 (75, 124) | 100 (81, 125) | 0.438 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m 2 ) | 72.5 ± 35.7 | 82.7 ± 30.3 | <0.001 | 75.8 ± 34.3 | 75.1 ± 25.7 | 0.802 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Unfractionated heparin | 194 (83.6%) | 655 (66.0%) | <0.001 | 178 (82.8%) | 177 (82.3%) | 0.899 |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 42 (18.1%) | 194 (19.5%) | 0.780 | 41 (19.1%) | 44 (20.5%) | 0.716 |

| Glycoprotein inhibitors | 42 (18.1%) | 86 (8.7%) | <0.001 | 39 (18.1%) | 32 (14.9%) | 0.363 |

| Angiographic data | ||||||

| Operator experience † | ||||||

| < 100 PCIs | 14 (6.0%) | 24 (2.4%) | 14 (6.5%) | 11 (5.1%) | ||

| 100 – 499 PCIs | 2 (0.8%) | 174 (17.5%) | <0.001 | 2 (0.9%) | 6 (2.8%) | 0.307 |

| ≥ 500 PCIs | 216 (93.1%) | 795 (80.1%) | 199 (92.6%) | 198 (92.1%) | ||

| PCI sheath size (5Fr/6Fr/7Fr/8Fr) | 2/168/60/2 | 27/915/51/0 | <0.001 | 2/155/58/2 | 2/202/11/0 | <0.001 |

| Sheath site (Left/Right) | 17/215 | 323/670 | 17/208 | 42/163 | ||

| PCI indications | ||||||

| Primary | 68 (29.3%) | 159 (16.0%) | 65 (30.2%) | 62 (28.8%) | ||

| Early invasive | 111 (47.8%) | 356 (38.9%) | <0.001 | 98 (45.6%) | 94 (43.7%) | 0.742 |

| Elective | 53 (22.8%) | 448 (45.1%) | 52 (24.2%) | 59 (27.4%) | ||

| Number of narrowed coronary arteries | ||||||

| 1 | 157 (67.7%) | 717 (72.2%) | 142 (66.0%) | 137 (63.7%) | ||

| 2 | 54 (23.3%) | 231 (23.3%) | 0.022 | 51 (23.7%) | 63 (29.3%) | 0.262 |

| 3 | 21 (9.1%) | 45 (4.5%) | 22 (10.2%) | 15 (7.0%) | ||

| Number of stents | 1.54 ± 0.74 | 1.53 ± 0.79 | 0.576 | 1.59 ± 0.76 | 1.58 ± 0.78 | 0.836 |

| Total stents length (mm) ∗ | 33 (23, 57) | 32 (22, 52) | 0.127 | 44.9 ± 29.7 | 45.9 ± 31.7 | 0.422 |

| Diffuse lesion (≥20 mm) | 154 (66.4%) | 621 (62.5%) | 0.274 | 146 (67.9%) | 158 (73.5%) | 0.204 |

| Bifurcation | 16 (6.9%) | 170 (17.1%) | <0.001 | 15 (7.0%) | 17 (7.9%) | 0.713 |

| Severe tortuousness | 14 (6.2%) | 63 (6.7%) | 0.718 | 16 (7.4%) | 22 (10.2%) | 0.308 |

| Severe calcified lesion | 20 (8.6%) | 146 (14.7%) | 0.015 | 19 (8.8%) | 28 (13.0%) | 0.164 |

| Chronic total occlusion | 32 (13.8%) | 38 (3.8%) | <0.001 | 32 (14.9%) | 31 (14.4%) | 0.892 |

| Left main narrowing | 9 (3.9%) | 48 (4.8%) | 0.534 | 8 (3.7%) | 8 (3.7%) | 1.000 |

∗ The variables with skewed distributions are shown as the median (the first quartile, the third quartile).

† Operator experiences of each group in the, respective, approach.

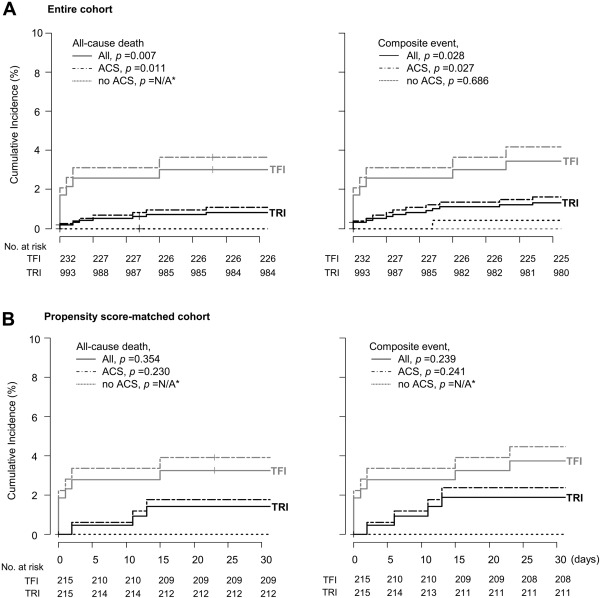

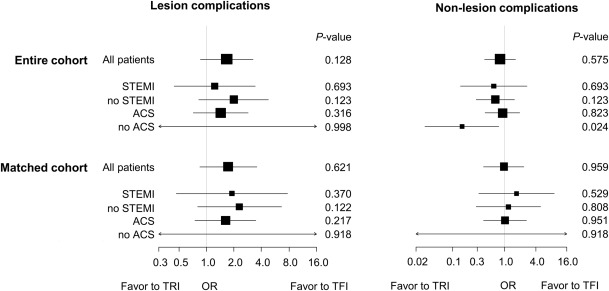

Kaplan–Meier analyses showed that in the entire cohort, the cumulative incidences of all-cause death and composite events within 30 days after PCI were higher in the TFI group than in the TRI group, whereas there were no differences in these measures between the 2 groups in the matched cohort. Although patients with ACS experienced all-cause death and composite events more frequently than patients without ACS, the event rates were not significantly different between the 2 groups in the matched cohort ( Figure 2 ). In the entire cohort, procedure failures, nonlesion complications, and major bleeding events were more frequent in the TFI group, whereas the overall frequency of complications and the frequencies of lesion complications, access site complications, and minor bleeding events were not different between the groups. In contrast, in the matched cohort, there were no differences in procedure failures, overall complications, lesion and nonlesion complications, access site complications, or major and minor bleeding events between the groups ( Table 2 ). Multiple logistic regression analyses also showed that TRI was not associated with a risk of lesion and nonlesion complications, in both the entire cohort and matched cohort after adjustments for confounders. There were no differences in the risks of complications for all subgroups except for the non-ACS group of the entire cohort, in which TRI was associated with a lower risk of nonlesion complication ( Figure 3 ).

| Outcomes | Entire Cohort | Propensity Score-Matched Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFI (N = 232) | TRI (N = 993) | OR (95% CI) | P for Inequality ∗ | TFI (N = 215) | TRI (N = 215) | OR (95% CI) | P for Inequality ∗ | |

| Procedure failure | 9 (3.9%) | 15 (1.5%) | 2.63 (1.00 – 6.51) | 0.031 | 9 (4.2%) | 5 (2.3%) | 0.54 (0.14 – 1.85) | 0.416 |

| Any complication | 29 (12.5%) | 115 (11.6%) | 0.92 (0.59 – 1.47) | 0.734 | 27 (12.6%) | 33 (15.3%) | 1.26 (0.70 – 2.28) | 0.487 |

| Lesion complication | 19 (6.9%) | 92 (9.3%) | 1.38 (0.78 – 2.56) | 0.303 | 16 (7.4%) | 26 (12.1%) | 1.71 (0.85 – 3.52) | 0.143 |

| Non-lesion complication | 17 (7.3%) | 30 (3.0%) | 0.39 (0.21 – 0.78) | 0.004 | 15 (7.0%) | 12 (5.6%) | 0.79 (0.33 – 1.86) | 0.692 |

| Access site complication | 8 (3.6%) | 20 (2.0%) | 0.58 (0.24 – 1.53) | 0.219 | 7 (3.3%) | 8 (3.7%) | 1.15 (0.37 – 3.79) | 1.000 |

| Bleeding complication | 11 (4.7%) | 13 (1.3%) | 0.27 (0.11 – 0.67) | 0.002 | 9 (4.3%) | 6 (2.9%) | 0.80 (0.24 – 2.37) | 0.601 |

| Major bleeding | 6 (2.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0.08 (0.01 – 0.43) | 0.001 | 4 (1.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0.50 (0.00 – 3.50) | 0.685 |

| Minor bleeding | 5 (2.2%) | 11 (1.1%) | 0.51 (0.16 – 1.89) | 0.204 | 5 (2.3%) | 4(1.9%) | 1.51 (0.35 – 7.40) | 1.000 |

∗ The p value was produced using the Fisher’s exact tests with the TFI group as the control.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree