Heart failure (HF) and depression are debilitating diseases with significant effects on functional status and real and perceived quality of life. Despite many advances in therapy for HF mortality remains high. Depression and HF have been recognized to coexist but this does not imply a causative relation. Depressed patients develop more symptoms, have worse compliance with medication regimens, are slower to return to work and social activities, and seem to have a poorer quality of life. In patients with known cardiac disease depression also predicts future events independent of disease severity and other risk factors such as smoking or diabetes mellitus. In conclusion, this review attempts to address the cause/effect relation, if any, between HF and depression and the role of treatment of depression in the setting of HF.

Heart failure (HF) and depression have profound effects on functional status and quality of life. Considering the high coprevalence of HF and depression this review addresses factors that are common to the 2 conditions and outlines reasons that a cause/effect relation may be too simplistic. Indeed, HF and depression may create a vicious cycle in which they worsen each other, leading to their combination being more severe than the additive effects of each considered in isolation. HF affects approximately 5 million Americans with 550,000 new cases diagnosed each year. Mortality of HF remains high with approximately 20% dying within 1 year of their diagnosis and a 5-year mortality of 59% in men and 45% in women despite advances in therapy. Depression has been predicted to increase in incidence and occurs in 1 of 6 residents in the United States. It is a global burden and appears to increase the incidence of other co-morbidities such as diabetes and coronary artery disease in addition to increased mortality from suicides.

Coexistence of Depression and HF

Depressed patients develop more symptoms, have worse compliance with medication regimens, are slower to return to work and social activities, and seem to have a poorer quality of life. In patients with known cardiac disease depression also predicts future events independent of disease severity and other risk factors such as smoking or diabetes. Data specifically identifying depression as a cause for development of HF are lacking but it is likely that an association exists between the 2 conditions. Women have a greater risk of developing HF (hazard ratio 1.96) even after adjustment for co-morbidities. Clinically significant depression has been reported in 21.5% of patients with HF in general with estimates of the prevalence of patients with HF and depression varying from 11% to 35% in the outpatient setting and 35% to 70% in the inpatient population. Occurrence of depression in HF also varies depending on whether questionnaires (19%) or diagnostic interviews (33%) are used to detect depression and by New York Heart Association classification HF severity (11% in class I vs 42% in class IV). Clarke et al showed that psychosocial factors including several related to depression predicted functional status after 1 year in patients with left ventricular dysfunction and Jiang et al showed that major depression in patients with HF was associated with a twofold increase in mortality and a threefold increase in hospitalization independent of any other identified risk factors. Patients who have concurrent HF and depression also have increased medical costs of 25% to 40%. A history of depression in patients with HF at hospitalization is a predictor of increased length of stay and increased 60- to 90-day mortality.

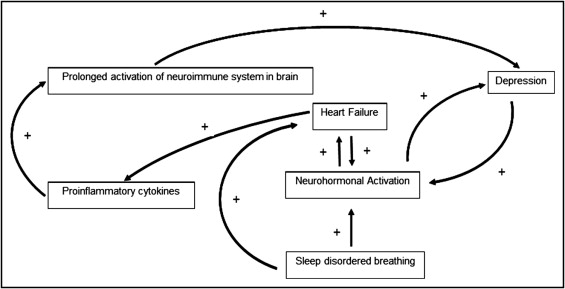

Evaluation of depression and HF across ethnic groups is limited. Non-Hispanic blacks with chronic HF had higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to Hispanics. Higher levels of depression were noted in women than in men (37% vs 33%) and nonwhites than in whites (77% and 67%, respectively) despite generally high levels of support with a lack of support associated with an increase in cardiac events. Despite extensive research ( Table 1 ) the interaction between HF and depression is incompletely understood. However, many common pathways and feedback loops may link HF and depression ( Figure 1 ) . These interactions can worsen HF and depression contributing to further decompensation in the 2 conditions.

| Study | Study Type | LVEF | Subjects | Duration (months) | Conclusion of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gottlieb et al (2004) | Prospective | <40% | 155 | 12 | Age, gender, and race similar to general population; treatment may improve QOL |

| Faller et al (2007) | Prospective | 231 | 33 | Depression produced poorer outcomes in patients with HF; prevalence 13% and associated with high mortality | |

| Bekelman et al (2007) | Cross sectional | 60 | Depression was associated with decrease in QOL; treatment of depression may improve QOL | ||

| Bekelman et al (2007) | Cross sectional | 60 | Spiritual well-being may improve QOL and decrease HF | ||

| Fonarow et al (2008) | Prospective | 4,861 | 2–3 | No difference in mortality by day of admission or discharge for HF hospitalizations | |

| Sherwood et al (2007) | Prospective | <40% | 204 | 36 | Depression was associated with adverse prognosis in HF; worse outcomes with antidepressant therapy |

| Lesman-Leegte et al (2009) | Prospective | 958 | 18 | Depression was associated with poor outcomes in patients with HF | |

| Angermann et al (2007) | Double-blind placebo-controlled RCT | <40% | 700 | 12–24 | Effects of escitalopram on mortality, depression, anxiety, cognitive function, QOL, expenditures; result pending |

| Gottlieb et al (2007) | Double-blind placebo-controlled RCT | 28 | 3 | Paroxetine CR decreased depression significantly in patients with HF | |

| O’Connor e al (2010) | Double-blind placebo-controlled RCT | <45% | 469 | 3 | Sertraline did not improve depression in patients with HF |

| Yeh et al (2011) | Single-blind parallel-group RCT | <40% | 100 | 12 weeks | Tai chi exercise may improve QOL, mood, and exercise self-efficacy in patients with HF |

Molecular pathways and mechanisms can be grouped into 4 categories: neurohormonal activation, inflammatory mediators, arrhythmias, and hypercoagulability.

Neurohormonal activation

A compensatory mechanism in response to physiologic stress over time, neurohormonal activation and autonomic hyperactivity become pathologic and contribute to worsening left ventricular function rather than compensation. Autonomic arousal and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis hyperactivity causes vasoconstriction and volume expansion. Initially this maintains perfusion during low-output states but eventually increases blood pressure. As this develops the heart’s ability to respond appropriately is overwhelmed by excessive afterload and volume expansion, leading to worsening cardiac function. This causes further increases in sympathetic tone, activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, and development or worsening of HF. These pathways have also been linked to the development of depression. This creates a feedback loop in which these diseases upregulate and worsen the same processes that initially caused them. When HF and depression coexist in patients, disease management programs for HF may not be effective.

Inflammatory mediators

Patients with HF have increased proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1, interleukin-2, interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and tumor necrosis factor, which may contribute to development of HF. Initially the inflammatory cascade is protective because it allows the heart to respond appropriately to physiologic stress through cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and protection from apoptosis. However, as HF progresses these cytokines become maladaptive and play an important role in ventricular remodeling, uncoupling of β-adrenergic receptors, apoptosis, and contractile dysfunction resulting in pathogenesis of HF. Inflammatory pathways also activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis, which can be pathologic and feed into the negative loop described in the previous section. Levels of proinflammatory cytokines correlate with disease severity and markers of inflammation such as high-sensitivity-C reactive protein and D-dimer may be used to monitor therapy of acute HF exacerbations. Depression has also been identified as a cause of inflammation and markers such as high-sensitivity-C reactive protein, fibrinogen, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-6 are increased in depressed patients with no cardiac disease.

Arrhythmias

Arrhythmias are a major cause of morbidity in patients with HF with 25% to 50% of deaths in this condition considered arrhythmogenic. Decreased heart rate variability (HRV) occurs in HF and has been associated with arrhythmias and increased morbidity and mortality. Decreased HRV is a marker of decreased parasympathetic tone, which exposes the heart to unopposed stimulation by sympathetic nerves and thus may provoke ventricular arrhythmias. High levels of norepinephrine and interleukin-6 are associated with decreased HRV, implying that autonomic arousal, inflammation, and arrhythmias may be interrelated. Depressed patients have a similar tendency to arrhythmias and decreased HRV even in the absence of HF, which could indicate a similar imbalance between autonomic sympathetic/parasympathetic balance and regulation. Depression also is associated with longer QT intervals, decreased baroreflex cardiac control, and ventricular arrhythmias. Although there is no evidence that these create a tendency toward worsening depression, given the high prevalence of sudden cardiac death in patients with HF this arrhythmogenic tendency of depression may contribute to a synergistic effect. Several antidepressant drug classes, particularly tricyclic antidepressants, are known to decrease HRV and cause prolonged QT intervals, which have implications for treatment decision. There is some early evidence, however, that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have a protective effect, but this needs further study.

Hypercoagulability

Although hypercoagulability has been linked to HF most directly in the setting of ischemic cardiomyopathy, data demonstrating a relation between hypercoagulable states and depression are less clear. It is known that HF contributes to a hypercoagulable state and that anticoagulation lowers mortality but a causal relation has not been established. Patients with HF have higher levels of von Willebrand factor, plasma viscosity, and fibrinogen and platelet activity. Anxiety and psychological stress may precipitate hypercoagulability owing to activation of the coagulability and inhibitory activities of the fibrinolytic system.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree