Study

Number of patients with CPFE/with IIPs

Prevalence (%)

Akira et al. [8]

15/80

18.8

Choi et al. [9]

66/254

26.0

Copley et al. [10]

76/212

35.8

Doherty et al. [11]

9/23

39.1

Jankowich et al. [12]

20/44

45.5

Kurashima et al. [13]

221/660

33.5

Mejía et al. [14]

31/110

28.2

Ryerson et al. [15]

29/365

8.0

Schmidt et al. [16]

86/169

50.9

Sugino et al. [17]

46/108

42.6

Most of cohort studies have demonstrated that CPFE is often observed in males over 65 years of age who are current smokers or ex-smoker of >40 pack-years [6, 7] (Table 13.2). However, despite demonstrating a similar smoking history and pulmonary function profile, CPFE associated with CTDs was observed more female dominantly and younger than “classic CPFE” [20].

Table 13.2

Clinical characteristics of CPFE

Study | No. | Age (y) | Male/female | Ever smokers/total patients | FEV1/FVC | FVC (%) | TLC (%) | DLco (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Akagi et al. [33] | 26 | 65 ± 9 | 23/3 | 24/26 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 86.6 ± 24.0 | 78.2 ± 17.4 | 45.3 ± 15.0 |

Cottin et al. [4] | 61 | 65 ± 10 | 60/1 | 61/61 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 90 ± 18 | 88 ± 17 | 37 ± 16 |

Cottin et al. [20] | 34 | 57 ± 11 | 23/11 | 30/34 | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 85 ± 24 | 82 ± 17 | 46 ± 16 |

Jankowich et al. [12] | 20 | 69 ± 10 | 20/0 | 20/20 | 0.67 ± 0.12 | 77 ± 14 | 76 ± 11 | 29 ± 11 |

Kitaguchi et al. [19] | 47 | 70 ± 1 | 46/1 | 46/47 | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 94.7 ± 3.5 | NA | 39.6 ± 2.5 |

Kurashima et al. [13] | 221 | 71 ± 8 | 209/12 | 221/221 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | 87.1 ± 17.0 | 93.9 ± 17.2 | 65.2 ± 20.9 |

Mejía et al. [14] | 31 | 67 ± 7 | 30/1 | 24/31 | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 62.1 ± 15.6 | NA | NA |

Ryerson et al. [15] | 29 | 70 ± 9 | 20/9 | 29/29 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 79.8 ± 15.7 | 78.9 ± 14.4 | 37.1 ± 14.0 |

Sugino et al. [17] | 46 | 71 ± 7 | 43/3 | 45/46 | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 93.9 ± 22.4 | 90.0 ± 16.4 | 49.8 ± 14.1 |

13.3 Physical Findings

Exertional dyspnoea (functional class III or IV of the New York Heart Association) is the most common symptom despite of relatively normal spirometric values among CPFE patients [4]. Physical examination often reveals bibasilar inspiratory crackles and finger clubbing. Other signs and symptoms reported are cough, sputum production and asthenia among CPFE patients [4].

13.4 Radiological Features

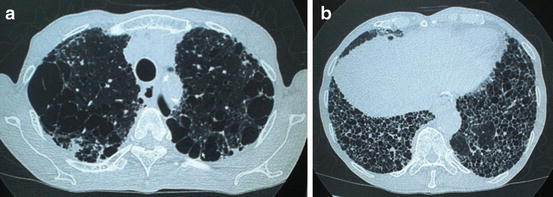

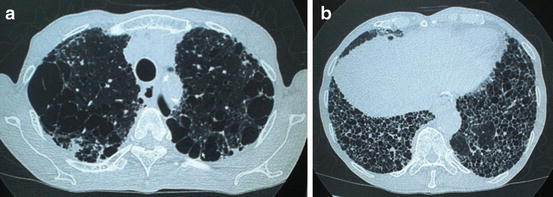

Radiological findings of CPFE are considered to be characterized by emphysema at upper lobes and fibrosis at lower lobes. On chest X-ray findings of CPFE, an interstitial pattern or reticulonodular infiltration is present at basal periphery of bilateral lungs, while a hyperlucency with thinning or reduction in pulmonary vessels is observed at bilateral apices. However, HRCT scanning is the most appropriate tool for the diagnosis of CPFE, because the estimation by chest X-ray alone does not necessarily confirm the diagnosis of this entity (Fig. 13.1).

Fig. 13.1

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of a male smoker aged 77 years with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. (a) Presence of paraseptal emphysema and subpleural bullae in bilateral upper lobes. (b) Images of subpleural honeycombing and traction bronchiectasis in bilateral lower lobes

Cottin et al. described the radiological criteria to determine CPFE as follows: firstly, the presence of emphysema on HRCT, defined as well-demarcated areas of decreased attenuation in comparison with contiguous normal lung and marginated by a very thin (<1 mm) wall or no wall, and/or multiple bullae (>1 cm) with upper zone predominance, and, secondly, the presence of diffuse parenchymal lung disease with significant pulmonary fibrosis on HRCT, defined as reticular opacities with peripheral and basal predominance, honeycombing, architectural distortion and/or traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis; focal ground-glass opacities and/or areas of alveolar condensation may be associated but should not be prominent [4].

UIP is the most common pattern [4, 9, 18, 19], as reporting the most frequent presence of honeycombing in the wide variety of HRCT findings of CPFE. Other patterns reported in pulmonary fibrosis include reticular opacities, ground-glass opacities, traction bronchiectasis and architectural distortion, which are compatible with non-UIP, smoking-related interstitial pneumonia (IP) or unclassifiable interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) (Table 13.3).

Table 13.3

Various HRCT findings in CPFE

CT findings | Study | |

|---|---|---|

Cottin et al. [4] | Kitaguchi et al. [19] | |

Fibrosis | ||

Honeycombing | 95 % | 75.6 % |

Reticular opacities | 87 % | 84.4 % |

Ground-glass opacities | 66 % | 62.2 % |

Traction bronchiectasis | 69 % | 40.0 % |

Architectural distortion | 39 % | 15.6 % |

Consolidation | 15 % | 13.3 % |

Emphysema | ||

Centrilobular | 97 % | |

Centriacinar | 24.4 % | |

Centriacinar + panacinar | 15.6 % | |

Paraseptal | 93 % | 33.3 % |

Paraseptal + centriacinar | 26.7 % | |

Bullae | 54 % | |

The various findings of emphysema also are present at upper lobes, including centrilobular, paraseptal and bullous change [4, 12, 17, 19, 20]. Centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema appear to be typical features of CPFE (Table 13.3). In the various findings of emphysema, Sugino et al. indicated a paraseptal emphysema as a predictor of poor prognosis among 46 CPFE patients [17].

13.5 Pathological Features

As the wide variety of radiological findings correlate closely with histopathological data, UIP is the most common pattern of pathological findings in accordance with the most frequent presence of honeycombing in HRCT findings of CPFE [4, 9]. Other patterns reported in pathological findings include nonspecific IP, desquamative IP, respiratory bronchiolitis-related ILD and unclassifiable ILD [4, 9, 18, 19]. Because of the pathological heterogeneity, a pathological criterion for diagnosis of CPFE is not mapped out [12].

13.6 Pulmonary Function and Gas Exchange

Pulmonary function tests show normal or subnormal findings of respiratory volume and flow, despite of severe dyspnoea on exertion and extensive radiographic findings among CPFE patients [4]. The coexistence of emphysema and fibrosis leads to an influence of pulmonary function that profiles each other in CPFE. Forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and total lung capacity (TLC) are usually within normal or subnormal range (Table 13.2). The unexpected subnormal spirometric findings in CPFE may be explained by counterbalancing effects of the restrictive disorder in pulmonary fibrosis and the propensity to hyperinflation in emphysema [5, 6]. The hyperinflation and increased pulmonary compliance in emphysema probably compensate for the loss of volume in fibrosis, resulting in the preservation of spirometric findings.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree