Chapter Six

Closing the Gap: Strategies to Effect Change

We have seen in previous chapters that women are at significant risk for death from cardiovascular disease. Women remain undertreated and underserved. More women than men die of heart disease every year. Women tend to present with more severe disease, more advanced disease and have more negative outcomes when undergoing procedures for revascularization. Even though there are well-established evidence-based therapies for treating acute coronary syndrome (ACS), guidelines and aggressive therapies are more likely to be applied in men. One of the most important factors in predicting survival and limiting myocardial damage in ACS is the time to revascularization. Due to delays in diagnosis and a perceived reluctance to treat women as aggressively, outcomes are often negatively affected.

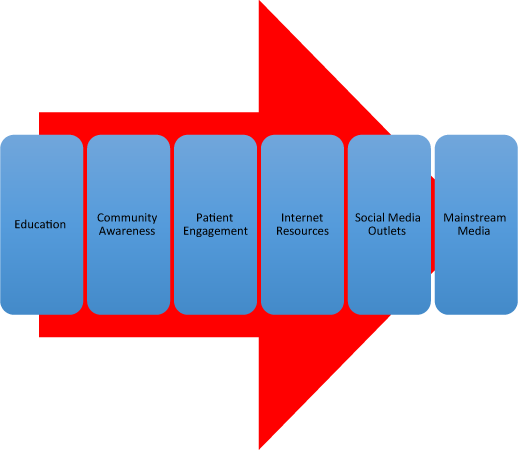

As a society, we must make a concerted effort to close the gender gap in cardiovascular care. As physicians and healthcare providers, we must ensure that we apply the same practice guidelines and evidence-based therapies in both sexes. Women and their friends and families must advocate for their healthcare needs. Women must become more engaged in their own heart health in order to effect change. The best way to effect change is to attack the problem of gender disparities in heart care from multiple fronts.

Figure 6.1 Strategies to close the gender gap in cardiovascular care for women.

1. Education of Physicians and Healthcare Providers

2. Community Awareness Efforts

3. Patient Engagement & Individual Responsibility

4. Internet Resources

5. Social Media Outlets

6. Mainstream Media Efforts

Education of physicians and healthcare providers

Change must begin within the healthcare system. As physicians and healthcare providers we must recognize that the gender gap exists and then begin to educate ourselves on ways in which we can improve care for all women. Physicians are now busier than ever, seeing more patients in less time. Patients are living longer with chronic disease and a primary care visit can become increasingly complex. It can be difficult to tease out subtle symptoms and risk profiles in women that may suggest heart disease and indicate a need for further testing. However, we must begin to proactively screen our female patients on a regular basis.

So much of the successful doctor–patient relationship in medicine is dependent upon effective communication. Even with the added time pressures and the increased patient load, we must ensure that we take the time to actively engage with our female patients. Just as educators must understand the learning style of their students, physicians and healthcare providers we must do a better job understanding how each of their patients are best served during an office visits. Some patients prefer a more interactive and participatory style of encounter while others prefer a more dictatorial form of healthcare interaction. There is a large body of evidence in the literature that has examined the ways in which doctors and patients interact — many of these findings surprisingly indicate gender-specific differences.

Many women may be hesitant to discuss symptoms with their doctor and sometimes it takes several visits to get to know a patient well enough that she will begin to relax and open up during a visit. Data also supports the fact that there are differences in the ways in which female patients interact with male versus female doctors.1 According to a study from the New England Journal of Medicine, female physicians are more likely to focus on preventative medicine and screening when compared with male colleagues.2 More importantly, female physicians were found to be more likely to communicate in a way that involved the patient during the office visit — more of a participatory “two-way street” interaction.3 Other studies have also demonstrated that female physicians are more likely to talk about lifestyle and habit modifications with patients in order to help prevent disease later in life.4,5 Gender-specific patient characteristics also play a role in the doctor–patient interaction. Women tend to want to spend more time in the office visit and prefer to communicate more history and symptom information (once comfortable with their providers).6 Female patients also seem to value more time spent by physicians explaining clinical situations than do male patients.7 There is great power in better understanding how patients best engage. We must spend the time necessary to determine the best style for each patient — through engagement we are more likely to collect more relevant data and identify the at-risk female patient.

Beyond the doctor–patient interaction, much can be accomplished through physician education. By their very nature, healthcare providers are scientists and respond well to data presented to them in order to effect changes in practice.8 However, the way in which physician behavior is changed in response to evidence is not uniform and remains a complex issue. An important first step is to make sure that as a healthcare community, physicians and other providers are better educated about the gender disparities in cardiovascular care. There are many opportunities for continuing medical education at all levels — national meetings, continuing medical education (CME) conferences and local and regional medical society meetings are wonderful platforms for the discussion of women and heart disease. While there are some programs in place to address gender disparities in cardiac care, there is simply a paucity of large-scale emphasis. Even more important is the fact that many of the most common educational interventions that are made in practice today are relatively ineffective. Data from multiple analyses has shown that traditional CME programs with didactic and printed materials are ineffective unless these activities are combined with follow-up, clinical reminders and chart audits.9 Adherence to guidelines significantly improves when traditional CME activities are combined with practice-specific follow-up activities that demonstrate change in physician behavior.

The best answer may be to create specific courses of study on women and heart disease and then help physicians develop chart reminder systems within their own electronic medical record systems. In addition, simple screening questionnaires have been developed by several organizations and these can be placed in the waiting room for female patients to complete while waiting for their appointments. Many of these screening questionnaires are based on a point system and can prompt the clinician to delve deeper into a cardiac-specific discussion during the office encounter. Some institutions such as the Mayo Clinic have developed a gender-specific Women’s Heart Clinic in order to serve the needs of female patients better.

No matter what approach we use, it is essential that all healthcare providers become more aware of the cardiovascular risks and the diagnostic challenges we face when treating women. We must work to assure that we educate ourselves, our colleagues and our patients about heart disease and its risk factors in order to effect change.

Community awareness efforts

Another critical component in closing the gender gap in cardiac care is better community education. We must not only ensure that physicians and other healthcare providers are aware of the disease prevalence in women; we must also make sure that those in our communities are aware of their own risk (and the risk of their family and friends). Campaigns such as the American Heart Association’s Go Red For Women have been widely successful. Each year in February, a particular Friday is set aside as Wear Red Day. This event, and others like it, raise awareness and increase exposure to communities all over the country. Go Red events such as galas, dinners and fashion shows are able to raise funds for promoting women’s health initiatives. The program encourages women of all ages to understand better and manage their risk for cardiovascular disease. These community-based awareness programs appear to be working but there is much more to be done. In a study published in 2012, researchers reported a significant increase in cardiovascular disease awareness among women between 1997 and 2012 — in fact, the rate of awareness nearly doubled from 30% to 56%.10 However, in the same study, there were large gaps in awareness seen between different racial/ethnic groups.

Patient engagement and individual responsibility

As with most things in medicine, patient engagement is critical to success. As healthcare providers we must strive to assist our patients in making changes. However, we cannot do this alone. We must work together with our patients — help them identify their own risk and then assist each person in formulating an individualized plan for change. Patients must also accept individual responsibility for lifestyle modifications to reduce risk such as weight loss, diet, exercise and smoking cessation. A review of the literature demonstrates that the most effective way to effect change is to involve the patient in the treatment decision-making process and develop a partnership.11 Both patient and doctor play a role and are held accountable for particular action items. No intervention will be successful without patient commitment. For example, in smoking cessation, regular follow-up is critical and making regular support mechanisms readily available to patients has been shown to increase both short term and long-term compliance rates.12 Effective communication between physician and patient will create a sense of shared goals and will help to empower each woman to take charge of her own cardiovascular health.

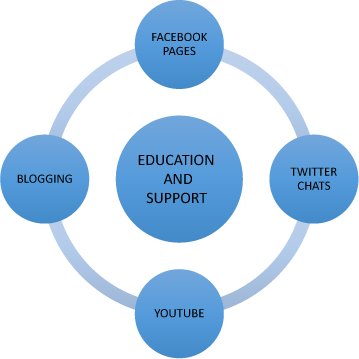

Figure 6.2 Process of patient engagement.

Internet resources

In today’s society nearly 60% of all adults have a smartphone or other mobile device. Most homes have at least one home computer and many are able to connect to the internet on a regular basis. The internet is widely available and offers access to vast amounts of information. Although quality control may be an issue with some websites — there are sites with valuable and reliable information. Many advocacy groups have taken advantage of this reach and have developed comprehensive websites targeted at women and heart disease. WomenHeart.org and GoRedForWomen.org are examples of quality internet resources. Laypeople can easily go to these sites for information and statistics surrounding heart disease in women. Moreover, when a healthcare professional is counseling a patient about heart disease and prevention these can be recommended reading for once the patient has left the office. Education experts have demonstrated that most people learn best and retain information most readily when they are exposed to concepts from multiple sources — in the case of heart disease and women these sources may include verbal doctor–patient interactions within the exam room, printed materials on heart disease and prevention and websites devoted to women’s heart health. Patients who receive reinforcement and multiple points of contact are more likely to be successful in lifestyle and risk factor modifications. The internet is another potential resource for both doctor and patient as they engage in care together.

Figure 6.3 Social media resources.

In battling heart disease in women we must use every tool available to increase awareness and effect change.

Social media outlets

As mentioned previously, we are now a digital society. Many of us are active on social media networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter. These social media outlets can be powerful tools for change. Each of these outlets has their own following but all of them can be utilized effectively in medicine to disseminate information, engage patients, educate the public as well as create support groups. Currently, Facebook is the second most visited website in the world behind Google. Facebook can be a wonderful tool to educate patients and increase awareness about heart disease in women. For instance, a Facebook “Women’s Heart Health Group Page” can be created and used as a platform to disseminate statistics about women and heart disease — ultimately resulting in improved community awareness. Twitter is a unique social media outlet that requires communication in 140 character messages. Twitter is valuable in that it can be used to create a buzz about an event (such as Go Red for Women) or it can draw attention to new developments in heart health that may appear on the news or in the press. Moreover, Twitter is an excellent venue to create virtual support groups. By identifying a particular conversation with a hashtag (#), a twitter chat can occur. Anyone who wants to join the chat simply searches for the tweets with the identified hashtag. For example, women who are working to stop smoking or reduce their risk for heart disease can join a chat that is identified as #womenshearthealth. These chats can be moderated by healthcare professionals and can serve as an effective means for encouraging lifestyle changes.

Mainstream media efforts

While social media and the internet are becoming more commonplace, the mainstream media remains a powerful tool for education and promoting community awareness of heart disease. The television media has improved their coverage of women’s heart health issues in recent years. Most morning news shows feature stories on women and heart disease during the Go Red for Women campaigns. These stories are important to increase community awareness and often can spur conversation among viewers. However, the mainstream media can do much more. As healthcare providers it is essential that we actively interact with media personalities in order to promote women’s heart health through interviews, promotional segments and charity events. Most local media professionals are always looking for stories that can directly impact the health of their viewers — stories on women and heart disease can have large and lasting effects.

1 Beach, M. C. and Roter, D. L. (2000). Interpersonal Expectations in the Patient-physician Relationship. J Gen Intern Med, Volume 15(11), 825–827.

2 Lurie, N., Slater, J., McGovern, P. et al. (1993). Preventive care for women: does the sex of the physician matter? New Eng J Med, Volume 329, 478–482.

3 Cooper-Patrick, L., Gallo, J. J., Gonzales, J. J. et al. (1999). Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA, Volume 282, 583–589.

4 Roter, D., Lipkin, M. and Korsgaard, A. (1991). Sex differences in patients’ and physician’s communication during primary care medical visits. Med Care, Volume 29, 1083–1093.

5 Elderkin-Thompson, V. and Waitzkin, H. (1999). Differences in clinical communication by gender. J Gen Intern Med, Volume 14, 112–121.

6 Wallen, J., Waitzkin, H. and Stoeckle J. (1979). Physician stereotypes about female health and illness: a study of patients’ sex and the informative process during medical interviews. Women Health, Volume 4, 135–146.

7 Hall, J. and Roter, D. (1988). Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care, Volume 26, 651–659.

8 Smith, W. R. (2000). Evidence for the effectiveness of techniques to change physician behavior. Chest, Volume 118, 8S–17S.

9 Bloom, B. S. (2005). Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: A review of systematic reviews. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, Volume 21, 380–385.

10 American Heart Association (2013). Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women. Circulation, 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318287cf2f.

11 Ong, L. M. L., de Haes, J. C. J. M., Hoos, A. M. et al. (1995). Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med, Volume 40, 903–918.

12 Ockene, J. K. (1987). Physician-delivered interventions for smoking cessation. Strategies for increasing effectiveness. Preventive Medicine, Volume 16, 723–737.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree