Etiology

Presentation

Risk factors

Arterial embolism

Acute catastrophe

Arrhythmia

MI/cardiomyopathy

Ventricular aneurysm

Rheumatic valve disease

Thoracic aortic thrombus

Arterial thrombosis

Acute/insidious, progressive

Atherosclerosis

Prolonged hypotension

Hypovolemia

Hypercoagulable state

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia

Acute/subacute

Hypovolemia/hypotension

Low cardiac output state

Alpha-adrenergic agonists, digoxin

Mesenteric venous thrombosis

Subacute

Hypercoagulable state

Malignancy

Inflammatory bowel disease

H/O DVT

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark of clinical presentation of a patient with AMI is abrupt onset, severe, nonlocalized abdominal pain out of proportion to physical signs; however, a more subacute/chronic presentation may be seen in patients with atherosclerotic disease of the mesenteric vessels. In some patients, there may be a total lack of physical findings in the early stages. Identifying risk factors and important clues in the clinical history is extremely important and can help make a timely diagnosis. Postprandial pain, unintentional weight loss, and food fear are all symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia which can progress to acute on chronic mesenteric ischemia. Patients may also present with a recent history of gastrointestinal issues including treatment of a small bowel obstruction or persistent abdominal discomfort after undergoing a cholecystectomy within the past year. Other associated complications that should be considered include ileus, peritonitis, pancreatitis, and GI bleeding that may mask the underlying AMI. A delay in diagnosis and treatment will invariably lead to bowel ischemia which can then develop into irreversible bowel necrosis, multisystem organ failure, and death.

Diagnostic Considerations and Imaging Studies

Once the diagnosis of AMI is suspected, it is often only confirmed with radiographic or intraoperative findings. Laboratory findings are nonspecific in the early stages of AMI and are for the most part noncontributory in making the diagnosis. By the time a patient is found to have leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis, elevated amylase levels, elevated liver function tests, or elevated lactate levels, the patient will have already developed bowel ischemia with frank peritonitis manifested as rebound tenderness and abdominal guarding on exam. In an experimental rat model, it has been suggested that the D-dimer level obtained two hours after an insult may correlate with the presence of AMI [14]. Further, plasma and urine levels of intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) have also been linked to bowel infarction in humans and have been suggested as tools in the early diagnosis of AMI [15–18].

Historically, plain X-rays of the abdomen were used to rule out other causes of acute abdomen, but in contemporary practice, these are of little use in making decisions regarding the definitive management of AMI. Computerized tomographic angiography (CTA) with intravenous contrast is now widely available and has replaced mesenteric arteriography as the definitive diagnostic tool in contemporary practice [19, 20]. It is a fast, effective, and noninvasive way to rule out more common causes of acute abdomen, confirm the diagnosis of AMI, and potentially identify the etiology [21]. In a patient that is stable, computerized tomographic angiography (CTA) has become the standard of care in diagnosing and guiding the treatment of AMI.

Mesenteric angiography was previously considered the “gold standard” due to the possibility of being both diagnostic and therapeutic. Its role has diminished as less invasive tests such as duplex ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and CTA have continued to improve in quality and availability. Over the past decade, the use of mesenteric angiography in the management of acute mesenteric ischemia in our experience decreased from 97 to 53 % of cases. Concomitantly, there was a rise in the use of CTA and MRA from 55 to 88 % and 12 to 33 %, respectively [22]. A major disadvantage of mesenteric angiography is that it can cause a delay in heparinization and definitive treatment of a patient presenting with severe AMI. Angiography is now indicated mostly in the treatment of in situ mesenteric arterial thrombosis with angioplasty with or without stenting, injection of intra-arterial vasodilators, thrombolysis, and aspiration thrombectomy. As a diagnostic modality, it may still be useful in select patients with extensive calcification, small vessels, or prior stents in place resulting in suboptimal imaging quality with noninvasive tests.

Duplex ultrasonography is an effective screening test for patients presenting with symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia. For example, if a patient presenting with subacute postprandial abdominal pain has a good quality duplex study with negative findings, the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia can be ruled out. One study showed that duplex ultrasonography can be relatively reliable in identifying a greater than 50 % stenosis in the mesenteric vessels with a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 93, 100, and 95 %, respectively, for the celiac trunk and 90, 91, and 91 %, respectively, for the SMA [23]. In order to obtain the most optimal images with duplex ultrasonography, patients are asked to undergo a 6–8-h fast prior to the test. Thus, in an acute setting, duplex is not often useful because abdominal tenderness and gaseous bowel distension impede the ultrasound technologist’s ability to visualize the mesenteric vessels. In addition to being heavily operator dependent, the patient’s body habitus can greatly affect the quality of the images obtained.

Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRA) is another option for imaging of the mesenteric vessels as well as the surrounding viscera. It was previously the preferred mode of imaging for patients with chronic kidney disease; however, more recent reports of gadolinium-related systemic fibrosis have curtailed its use in these patients. Nevertheless, it is a reliable imaging modality for identifying stenosis in the visceral vessels with a sensitivity of 92 %, specificity of 84 %, PPV of 65 %, NPV of 97 %, and accuracy of 86 % [24]. When compared with CTA, the main advantage of MRA is that the patient is not exposed to ionizing radiation. The drawbacks of MRA include lower spatial resolution and potential artifacts from previously placed stents which can limit its ability to identify clinically relevant mesenteric vessel stenosis [25]. Furthermore, longer acquisition times and limited availability make MRA a less practical option for patients presenting acutely with mesenteric ischemia.

Computerized tomography angiography (CTA) with intravenous iodinated contrast has many of the same advantages of the other noninvasive studies discussed but is a more effective test for ruling out other common causes of acute abdomen, confirming the diagnosis, and potentially identifying the etiology of AMI [26]. CTA has become more widely available and is now the standard of care as the definitive diagnostic tool in contemporary practice [27, 28]. In one study comparing duplex ultrasonography, CTA, and MRA to conventional angiography, CTA was found to have the highest mean image quality and concordance rate with findings on digital subtraction angiography. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy for identifying a relevant stenosis in the celiac trunk (defined as greater than 50 % in this study) were highest for CTA with 100, 95, 86, 100, and 96 %, respectively [24]. In addition, CTA may also assist in identifying the etiology of mesenteric ischemia and in planning an appropriate intervention. With this in mind, a biphasic scan with arterial and venous phase would be the optimal study for discerning between mesenteric arterial occlusion and venous thrombosis. While the arterial phase may reveal arterial flow disruption secondary to thrombosis, embolus, dissection, or an aneurysm, the venous phase would be needed to show venous thrombosis. Regardless of findings, all patients diagnosed with AMI on CTA should receive appropriate resuscitation with intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics simultaneously. Further course of treatment is guided by the etiology identified and the acuity of presentation.

Overview of Management by Etiology

Critical patients with suspicion of acutely ischemic bowel or signs of peritonitis should be taken to the operating room directly for exploratory laparotomy regardless of the underlying etiology. Bowel viability is assessed at exploration, nonviable bowel is resected, equivocally viable bowel is preserved, and the causative pathology of AMI is addressed. This is performed simultaneously with resuscitation with IV fluids and antibiotics.

Noncritical patients with slower symptom progression and no peritoneal signs should be treated with initial mesenteric revascularization by endovascular means, surgical intervention, or systemic anticoagulation based on the etiology of AMI identified. Subsequently the ischemic bowel can be addressed with close observation, laparoscopy, or laparotomy depending on outcome and progression.

Arterial Embolism

Arterial embolism is the most common etiology of AMI and accounts for 40–50 % of patients with AMI. The thrombus usually originates in the heart of a patient with atrial fibrillation, recent myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, left ventricular aneurysm, or valvular heart disease and lodges in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) a few centimeters distal to the orifice near the origin of the middle colic artery. On CTA the proximal SMA is often patent and without calcification with a filling defect seen at the site of the embolus (Fig. 15.1). Thus, the affected area of bowel is often limited to the distribution of the occluded vessel with clear demarcation that will often spare the proximal jejunum. Bowel wall findings on CTA may include increased thickening, dilatation, and attenuation. Pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous air, mesenteric edema, and ascites are other CTA findings associated with bowel ischemia. At exploratory laparotomy, the entire bowel is inspected carefully. Visual inspection of normal color and peristalsis alone is sometimes misleading and other modalities to assess bowel viability include palpable pulses in the mesentery, dopplerable arterial signals on the antimesenteric border of the bowel, bleeding from the cut ends, inspection for perfusion under a Wood’s lamp after fluoroscein injection, surface oximetry, and laser tissue flowmetry [29]. Balloon catheter thromboembolectomy is performed with removal of the thrombus from the SMA, and flow is restored to the bowel. Segments of obviously necrotic bowel are resected, and bowel continuity is restored only after revascularization is completed and vascularity of the ends has been determined to be satisfactory. In most instances, it is prudent to preserve all equivocal segments of bowel for reassessment at a second look laparotomy in 24–48 h.

Fig. 15.1

Three-dimensional reconstruction of a CT angiogram demonstrating an occlusive acute arterial embolus in the SMA

Acute Arterial Thrombosis

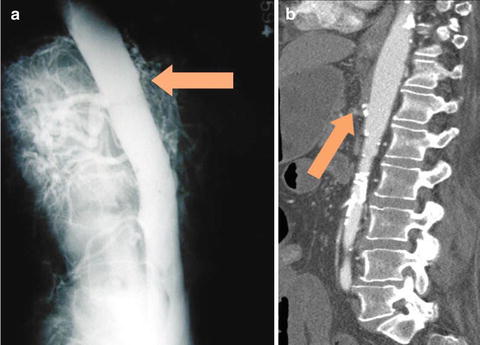

Acute arterial thrombosis superimposed on preexisting severe atherosclerotic disease and preexisting mesenteric arterial stenoses is the second most common cause of AMI, accounting for 25–30 % of cases [30]. Prior symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia can be elicited in 25–50 % of patients. Patients frequently present with a slower progression of symptoms, and the acuity and severity of the situation depend on the extent of preexisting arterial stenoses and degree of collateralization. Bowel infarction is more insidious in onset because extensive collaterals are able to maintain viability until there is final closure of a critically stenotic vessel or collateral. In fact, the natural history of mesenteric artery stenosis in the general population is benign, as described by Wilson et al. [31]. Asymptomatic mesenteric artery stenosis is not associated with either death or adverse cardiovascular events unless there is a history of prior bowel resection, which could result in loss of collaterals. As with arterial embolism, severely symptomatic patients with an acute abdomen should be taken directly to the operating room with the same strategy outlined above. Patients stable enough to undergo a CTA should have the study done; in acute mesenteric arterial thrombosis this will usually reveal ostial SMA occlusion in a calcified artery. In this setting, there is no sparing of the proximal jejunum, because the thrombosis extends to the origin of the SMA and across the proximal jejunal branches (Fig. 15.2). In the patients presenting with subacute symptoms and well-developed collateral vessels on CTA, mesenteric arteriography with stenting of the SMA is a viable option with potentially lower morbidity and mortality [4]. This approach is less optimal in severely symptomatic AMI patients due to the unavoidable delay in assessment of the bowel for possible necrosis. Intraoperative mesenteric bypass or retrograde stenting of the SMA during laparotomy are viable options in this situation, the latter being easier and superior especially when bowel resection is necessary [32, 33].