Delayed sleep phase type is the most common of the CRSDs

(7). It was first characterized by Weitzman et al. in 1981 Patients with DSPT report a chronic inability to fall asleep and wake up at a desired clock time to meet their work schedules, but do describe undisturbed late sleep on vacations

(8). In addition to delayed sleep, wake times the circadian phase of these patients, as measured by melatonin and core body temperature, is also delayed

(48,

49 and

50). In a study of 66 subjects, dim light melatonin onset occurred 2 hours later and core body temperature nadir 2.5 hours later than controls

(50). Furthermore, circadian phase appears stable in DSPT subjects across multiple measurements despite an ad libitum sleep schedule

(49). The exact pathophysiology of DSPT is unknown. However, several factors may be implicated in the persistent delayed sleep phase relative to the 24-hour environment, including circadian period, light sensitivity, phase angle, and the homeostatic sleep drive.

One proposed explanation is that patients with DSPT have a longer endogenous circadian period or

tau that regulates the sleep-wake cycle

(9). In one patient with DSPT placed in temporal isolation, circadian period measured 25.38 hours as compared to 24.44 hours in aged matched controls subsisting in the same environment

(51). Although the usual human circadian period is slightly longer than 24 hours, this further lengthening may result in difficulty entraining to the 24-hour day. Evidence also suggests that some patients with DSPT may be hypersensitive to evening light, which can serve as a delay signal to the circadian clock

(10). Alternatively, DSPT patients may have decreased sensitivity to morning light such that its phase advancing effects are reduced. However, other studies demonstrate that the advance portion of the phase response curve to light is actually masked due to sleep offset occurring relatively later with respect to the core body temperature nadir than normal controls

(52). Th is alteration of the relationship between sleep timing with respect to phase markers (or

phase angle) is another possible mechanism to explain DSPT, with studies demonstrating a significantly longer interval of time elapsing between the time of highest circadian propensity for sleep and wake time in these patients as compared to controls

(52,

53). Th is finding, in addition to increased slow wave sleep in the latter part of the sleep period, may suggest an abnormality in the dissipation of the homeostatic sleep drive

(51). The accumulation of homeostatic drive is likely altered as well since DSPT patients often demonstrate increased sleep onset latency (despite attempting sleep at the preferred times) and inability to sufficiently recover sleep after sleep deprivation

(51,

53,

54). Therefore, although DSPT is often regarded solely as a disorder of circadian timing, impairment of homeostatic regulation may play a significant role

(8,

11,

12). However, other evidence is not supportive of these findings with a study of 66 DSPT patients demonstrating no difference in sleep onset latency, total sleep duration, or phase angle as compared to controls

(50). Additionally, while evaluating the therapeutic response to a light mask in a group of DSPT subjects, two subgroups were delineated: those with melatonin acrophases prior to 0600 and longer sleep offset phase angles, and those with melatonin acrophases after 0600 and shorter sleep offset phase angles

(55). These findings could indicate the possibility of heterogeneity within DSPT patients. Finally, genetic factors are likely to play a role in the pathogenesis of DSPT. For example, there are familial forms of DSPT, and polymorphisms in circadian

genes such as

Per3, arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, HLA, and Clock have been reported in “evening types” and DSPT

(13,

14,

15 and

16).

Clinical Presentation

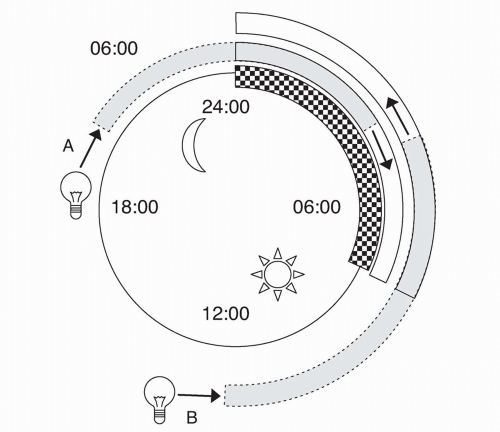

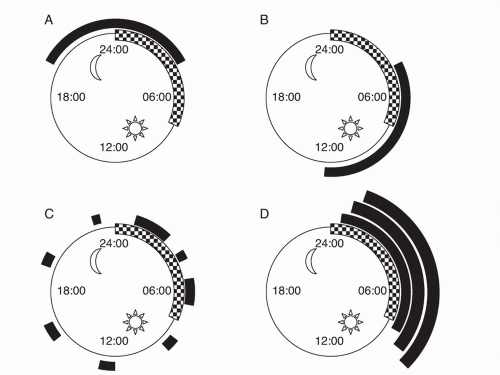

Although DSPT can present at any age, most patients are adolescents or young adults. Individuals with DSPT will present with sleep-onset insomnia and difficulty waking in the morning. Patients usually fall asleep between 2 and 6 AM and wake up between 10 AM and 1 PM

(8) (

Fig. 7.2). Early daytime sleepiness may be present, and these patients will score as “evening” types on self-assessment questionnaires such as the Horne and Ostberg

(17). Like “evening” types, patients with DSPT are most alert and active in the late evening hours; however, enforced conventional wake times will lead to chronic sleep deprivation and a persistent inability to fall asleep at an earlier time. In this sense, patients with DSPT are not able to “adapt” themselves to waking up early by going to sleep earlier, unlike unaff ected individuals. If a college student who is used to a delayed sleep-wake cycle joins the workforce, he or she will complain of morning fatigue. The patient probably does not have DSPT if he or she can adjust to the morning work routine in a few days or weeks.

Failure to attend morning classes or be on time for work will often lead to poor grades at school or disciplinary actions at work. On weekends or vacations, patients with DSPT will usually extend their sleep time significantly beyond that during the

weekdays

(18). Usually, a variety of methods of phase advancement (e.g., earlier bedtime, multiple alarm clocks) have been tried without success. Pharmacologic means of inducing sleep are also frequently tried (e.g., sedatives and alcohol) but may result in drowsiness the next morning or may lead to substance abuse

(19). Concurrent mood disorder may be present as patients with DSPT are more likely to have had treatment for emotional problems, answer yes on depression screening, and have higher scores on depression rating scores than age-matched controls

(56).

Epidemiology

DSPT is estimated to be present in approximately 0.17% of the general population

(20), and most reports show a male:female ratio of 10:1

(11). A survey of adolescents, however, indicated a prevalence of more than 7%

(21). The greater prevalence in adolescence may be a consequence of both physiological and behavioral factors

(59). Hormonal changes may be involved specifically, as delayed sleep phase is associated with the onset of puberty (when controlling for age)

(60). DSPT also accounts for approximately 7% of patients with chronic insomnia presenting to sleep clinics

(8). DSPT may be seen more frequently in populations with other neurological and medical disorders, with delayed circadian rhythms observed in traumatic brain injury, Huntington’s disease, and patients with liver cirrhosis

(57,

58,

69).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of DSPT is usually evident from a detailed history and a sleep diary or actigraphy for at least 7 days, which should include weekends with less strict social and work restrictions to ensure that the patient exhibits a delayed sleep-wake pattern. Actigraphy uses a wrist-worn motion detector (usually designed to look like a wristwatch) to monitor sleep and wake activity for prolonged periods (up to several weeks). In 2007, the AASM published practice parameters regarding the use of actigraphy, suggesting its use as a diagnostic tool in DSPT and as an assessment measurement for treatment outcomes in circadian rhythm sleep disorders as a guideline

(61). Overnight polysomnography is not routinely suggested by the AASM as part of the evaluation of DSPT; however, it may be indicated when complaints of sleep maintenance insomnia and daytime somnolence are present to rule out other sleep disorders such as sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder

(8,

62). If performed during the patient’s desired sleep time, sleep architecture should be normal with the exception of the sleep latency, which may be prolonged

(19). Although circadian phase markers may be helpful in the diagnosis of DSPT, they are not yet routinely used clinical practice

(63).