Chronic Rheumatic and Autoimmune Valve Disease

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Introduction

Postrheumatic or postinflammatory valve disease refers to scarring of the valve that occurs secondary to an autoimmune reaction following infection with group A streptococci. Acute valve disease occurs with the pancarditis of acute rheumatic fever and is associated with small sterile vegetations on the lines of closure of the mitral valve (see Chapter 147). The risks of the long-term development of chronic valve disease, which involves primarily the mitral and aortic valves, are discussed in Chapter 147.

Autoimmune valve disease also includes Libman-Sacks endocarditis with thrombotic vegetations associated with lupus erythematosus, as well as thrombotic endocarditis associated with antiphospholipid syndrome (Chapter 177). Chronic autoimmune valvulitis in autoimmune syndromes occurs most often in ankylosing spondylitis.

Chronic Rheumatic Mitral Valve Disease

Mitral Stenosis

There is a 20- to 40-year typical latent period between infection and initiation of symptoms, which are indolent for 10 years and then accelerate (see Chapter 147). The mean age at valve replacement has become later in developed countries. Most patients, who are more likely women than men, are over 60 at the time of valve repair or replacement.1

Medical treatment of postinflammatory mitral stenosis involves treatment of atrial fibrillation, endocarditis prophylaxis, and anticoagulation. Surgical treatment includes balloon valvuloplasty, if echocardiography demonstrates an absence of thrombus and significant regurgitation and shows favorable morphology. If there is marked distortion due to fibrosis and calcification, then open valve replacement is performed. The echocardiographic evaluation includes a score grading mobility, valve thickness, subvalvular thickening, and calcification; the score affects the decision between closed transcutaneous balloon procedure and open commissurotomy with possible valve replacement.

Mitral Insufficiency

Approximately one-fifth of patients with postinflammatory mitral valve disease have pure insufficiency; in all, 46% of patients have stenosis with insufficiency, and 34% pure stenosis.1 Mitral insufficiency is more likely caused by floppy mitral valve, and ischemia and endocarditis are other important causes (see Chapter 176).2

Gross Pathologic Findings

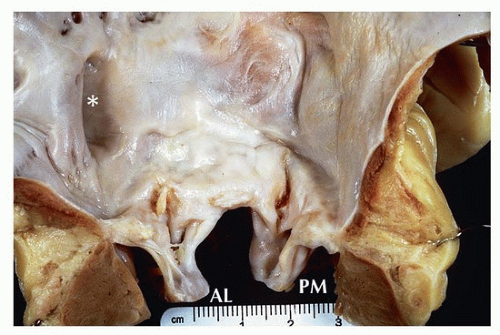

At autopsy, findings involve the valve itself and secondary effects of mitral stenosis or insufficiency on the atria and ventricles. The valve is usually white and scarred, with fibrosis at the two commissures, leaflets, as well as chordae (Figs. 174.1 and 174.2). The chords are thickened and fused. The chordae are normal in a minority of patients, but generally showing fusion and thickening.3 Lastly, the papillary muscles can also show scarring. Functionally, leaflet thickening and calcification, commissural fusion, chordal fusion, and the funnel-shaped orifice narrow the valve orifice. The valve ostium has a “fish-mouth” appearance when viewed from the atrial aspect, because of the thickened chordae and stenotic valve orifice (Fig. 174.2).

Secondary cardiac changes result in atrial dilatation, which may be massive and may be associated with mural thrombi. A characteristic, but nonspecific finding in the atrium is an area of endocardial fibrosis secondary to regurgitant jet stream called the “MacCallum plaque.”4 With long-standing disease, pulmonary hypertensive changes result in right ventricular hypertrophy and dilatation with tricuspid regurgitation5 (Figs. 174.3 and 174.4).

The surgical specimen is typically a valve replacement showing an intact valve with two intact leaflets (Fig. 174.5). Valve replacements are the preferred procedure, as most patients are not candidates for percutaneous valvotomy or surgical commissurotomy. The entire valve is excised because marked scarring prevents valve repair. Up to 69% of mitral valve replacements for postinflammatory disease have a

concomitant aortic valve replacement, a common association of valve disease in rheumatic fever.1,6,7

concomitant aortic valve replacement, a common association of valve disease in rheumatic fever.1,6,7

The gross appearance of the excised valve reveals thickened chordae and thickening of the valve leaflets (Fig. 174.5 and 174.6), in contrast to mitral valve prolapse. A fibrotic ridge is usually seen on the atrial surface at the line of closure.5 Calcification is common, usually at the ventricular aspects of the leaflets, giving rise to a rigid conical structure. Fracture and calcified foci with secondary deposits can be observed in some cases.7 Rheumatic valve disease predisposes to infectious endocarditis, which may be the cause for valve replacement (Fig. 174.7).

The morphology of postinflammatory mitral stenosis is distinct from postinflammatory regurgitation in the extent of calcification and fibrosis. In pure regurgitation, the leaflets are thickened, but commissural fusion is rarely seen. The fibrous thickening is less severe, and calcification is not commonly found.6 However, on gross examination, it is difficult to assess preoperative valve function, and it is helpful to refer to operative data and prior echocardiograms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree