12 Chronic Coronary Artery Disease

Patients with atherosclerotic CAD can present to health care providers in many different ways. This chapter focuses on chronic stable angina. Other clinical presentations of atherosclerotic CAD (acute coronary syndromes, congestive heart failure, sudden cardiac death, and cardiogenic shock) are described in separate chapters (13, 14, 17, 23, and 30).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

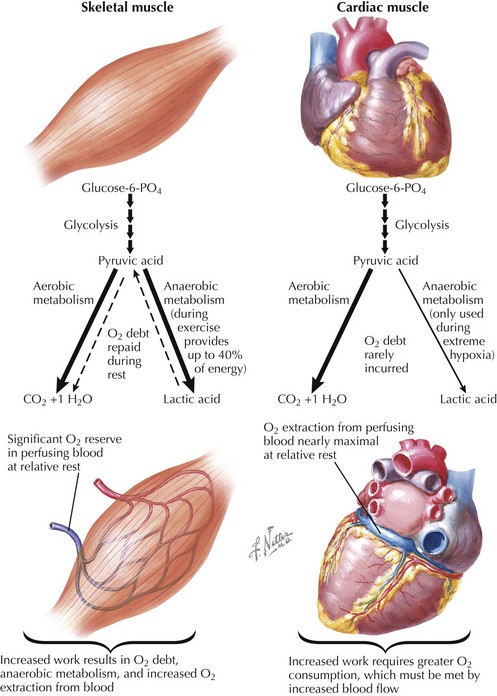

In contrast to oxygen extraction by skeletal muscle, oxygen extraction by cardiac tissue is near maximal, even at rest (Fig. 12-1). The heart responds to the need for increased cardiac output by increasing heart rate and contractility, both of which increase wall stress and myocardial oxygen requirements. This need for increased myocardial oxygen cannot be met by increasing the efficiency of oxygen extraction and thus must be met by increasing coronary blood flow. If a significant underlying coronary epicardial stenosis is present, blood flow at rest is maintained by compensatory dilatation of the coronary bed beyond the stenosis. This diminishes coronary flow reserve and may result in an inability to meet oxygen requirements as myocardial demand increases, creating a supply/demand mismatch. Symptoms of angina reflect myocardial ischemia and arise when the blood supply to a region of the heart cannot increase sufficiently to match myocardial oxygen demand as a result of the presence of a hemodynamically significant stenosis in the coronary artery supplying that region. Ischemia can be elicited by treadmill or bicycle exercise testing (or use of pharmacologic stress) and may be measured as loss of systolic thickening on echocardiography, diminished perfusion on single-photon emission CT, ST-segment depression on surface ECG, and angina.

Increased vasoreactivity (vasospasm on a previously narrowed arterial segment) may also result in decreased myocardial blood flow with or without increased demand. Vasoreactivity seems to be responsible for some of the circadian, seasonal, and emotional components associated with angina. Although it is thought that fixed coronary artery stenoses are the dominant contributor to stable angina, in some individuals there are clearly contributions from increased coronary vasoreactivity (both at sites of stenoses and elsewhere). The other major biologic mechanism that results in myocardial ischemia is rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery, resulting in sudden diminished blood flow and acute coronary syndromes, as discussed in Chapters 13 and 14.

Clinical Presentation

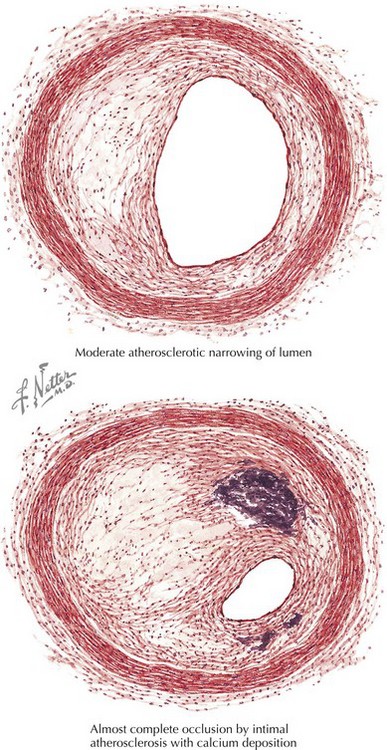

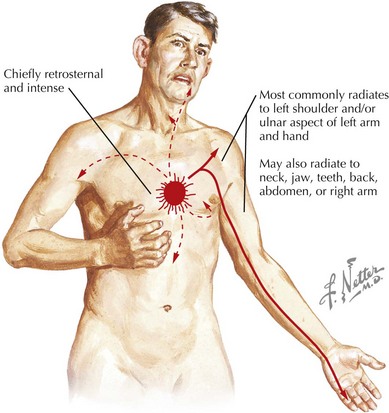

Chronic stable angina is characterized by angina that usually occurs with increased oxygen demand. Symptoms can be provoked by exertion, heavy meals, or emotional distress; they also tend to be reproducible and usually have been present over many months, or longer. As noted above, these symptoms most commonly result from fixed coronary stenoses (Fig. 12-2). Chest discomfort is typically described as a pressure or tightness, or discomfort over the left precordium, although many individuals with myocardial ischemia do not have these classic symptoms. The discomfort may radiate along the ulnar aspect of the left arm and is often accompanied by shortness of breath, nausea, and diaphoresis (Fig. 12-3). Symptoms may also radiate or be isolated to the throat, jaw, interscapular region, and epigastrium. Radiation below the umbilicus and to the occiput is uncharacteristic, as are symptoms that are well localized to a fingertip, provoked by palpation and movement, or relieved by lying down. Typically, stable anginal pain lasts for more than a few minutes and less than 10 minutes, is associated with exertion or other stresses, and is relieved by rest or the use of sublingual nitroglycerin within 1 to 2 minutes. Angina can sometimes be mistaken as indigestion, accounting for a delay in presentation or treatment. It is very important to understand that atypical presentations of angina can occur in any patient but are particularly common in diabetics, women, and the elderly. In these individuals, it is very important to evaluate further any exertion-related symptoms that may reflect an inability to increased myocardial oxygen delivery, including significant dyspnea on exertion, new or worsened fatigue with exertion, or similar symptoms.

Diagnostic Approach

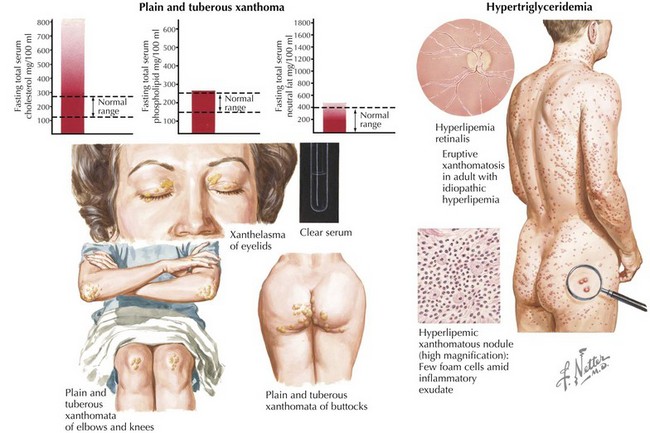

A history suggestive of angina mandates diagnostic and prognostic evaluations. The urgency of treatment is guided by the initial presentation and clinical evaluation. A history of new-onset angina, accelerating angina, angina at a low exertional threshold, and rest angina most often means that the patient is having an acute coronary syndrome and needs immediate evaluation and therapy. In an individual who has previously had stable angina who presents with a picture of acute coronary syndrome, if there is no evidence for myocardial ischemia, it is important to include consideration of whether a noncardiac cause of increased oxygen demand (such as anemia, hyperthyroidism, severe emotional stress, or like causes) has contributed to the worsening angina in that patient. Physical examination during a routine consultation is unlikely to be rewarding, but the clinician should look for clinical evidence of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (resting tachycardia, laterally displaced apical impulse, an LV S3, rales, jugular venous distention, positive hepatojugular reflex, pedal edema). In addition to evaluating the status of traditional cardiac risk factors (hypertension, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, diabetes), it is also important to inquire about a history of claudication, stroke, and transient ischemic attack and carefully screen for manifestations of atherosclerotic disease (audible bruits, asymmetric pulses, palpable aneurysms, ankle-brachial index). The presence of atherosclerosis in any of these areas heightens the likelihood of underlying CAD. The examiner should also look for physical and biochemical signs of the metabolic syndrome (Box 12-1), as well as stigmata of hereditary hyperlipidemic conditions (Fig. 12-4).

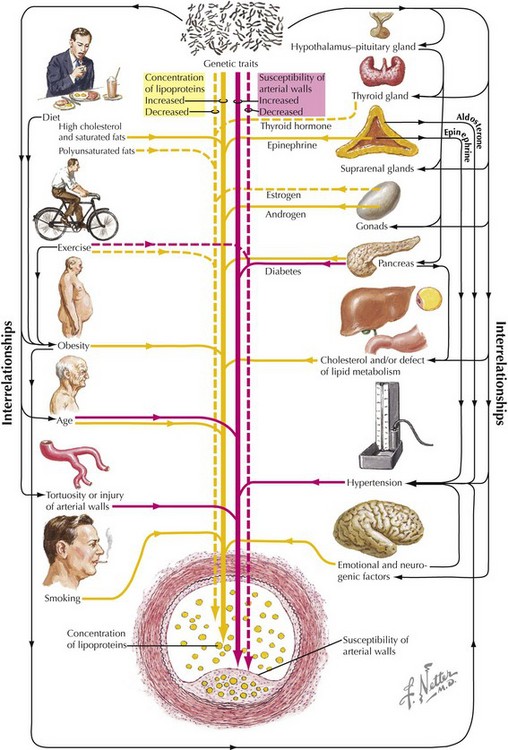

The next steps in the diagnostic approach should be based on the pre-test likelihood of disease. The interplay of traditional risk factors and genetic traits impacts the development of atherosclerosis (Fig. 12-5). Patients with typical angina, multiple risk factors, and/or impaired LV function with a high likelihood of disease should be considered for diagnostic coronary angiography. The few patients with a low pre-test likelihood of disease should be reassured, without further additional testing. In these individuals it is very important to emphasize risk reduction with smoking cessation and lifestyle modification.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree