History (angina or anginal equivalent)

Acute ischemic electrocardiogram (ECG) changes

Typical rise and fall of cardiac markers

Absence of another identifiable etiology

Occurring at rest or with minimal exertion and usually lasting >20 minutes (if not interrupted by nitroglycerin)

Severe pain of new onset (i.e., <1 month)

Occurring with a crescendo pattern (i.e., more severe, prolonged, or frequent than previously)

No evidence of myocardial infarction by biomarkers

Ischemic symptoms

Development of pathologic Q waves on the ECG

ST elevation, depression or evolutionary EKG changes consistent with ischemia

Post PCI (CK-MB 3× upper limit of normal)

Normal male pattern: Often with 1-3 mm of concave sinus tachycardia (ST) elevation greatest lead V2

Early repolarization: Often with 1-3 mm of concave ST elevation, often with notching at the J point in V4

Variant ST elevation with T wave inversion: Seen often in young black men, convex ST elevation, T wave inversion, thought to represent persistent juvenile T wave inversion + early repol, may look like STEMI

Left bundle branch block (LBBB): Typical pattern of LBBB present with anterior ST elevation

Pericarditis: Diffuse ST elevation and PR depression, PR elevation in AVR, the ratio of ST elevation: T wave height (> 0.25 measured using PR segment as the baseline in this case) in V6 is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of pericarditis

Left ventricular hypertrophy with strain

Hyperkalemia: Downsloping ST elevation associated with wide QRS, peaked T waves

Pulmonary embolism: Sinus tachycardia, often anterior T wave inversions

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (apical ballooning syndrome)

Brugada syndrome: Right bundle, downsloping ST elevation >2mm isolated to V1 and V2

TABLE 3-1 Immediately life-threatening causes (must consider these every time) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 3-2 Urgent causes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 3-3 Other causes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (apical ballooning syndrome)

Coronary vasospasm (Prinzmetal angina)

Coronary dissection

Severity: The 1-10 scale is useful, functional limitations should be sought

Onset: Be specific, can affect decisions about thrombolysis and PCI

Character: Pressure versus sharp, pleuritic, tearing (aortic dissection)

Radiation: Shoulder, jaw, arm, back

Associated symptoms: shortness of breath (SOB), nausea/vomiting (N/V), palpitations, syncope

Tempering factors: Rest, particular position (pericarditis—relief sitting forward)

Exacerbating factors: Exertion, emotional state versus particular position

Self assessment: Knowing the patient’s fears is important for many reasons

Also look for history of CAD, details of prior angiography, CABG or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), recent stress tests or echoes, other risk factors (DM, smoking, HTN, hyperlipidemia, cocaine use)

Hypotension/hypertension

Arrhythmias

Tachypnea or hypoxia

Fever

Bilateral SBP difference >15 mm Hg (think of aortic dissection)

Asymmetric pulses and/or a focal neurologic exam (aortic dissection)

Signs of heart failure (elevated JVP, S3, crackles, hemoptysis)

New MR murmur (? papillary muscle ischemia)

A new S4 in a patient with active CP is highly suggestive of ischemia

Murmur of aortic stenosis, pulsus parvus et tardus

Abdominal tenderness (biliary tract/pancreatic disease)

Rectal exam—evaluate for melena or guaiac positive stool (? how aggressive to anticoagulate)

Rash on the chest (Zoster), make sure to examine the chest on hospital day 2, the pain often precedes the skin findings!

Troponin I or T may be detectable as early as 2 hours after injury and CK-MB become detectable around 6 hours and are most sensitive at 10 hours

Myoglobin may rise somewhat sooner but is nonspecific

Must obtain serial tests q4-6 h for at least 10 hours after the start of CP to definitively r/o MI

False positive in heart failure, significant hypertension, PE

Look for typical rise and fall of enzymes in the context of CP and the ECG to make a diagnosis of NSTEMI

Heart failure can be responsible for persistent low-grade elevation of troponin thought to be from elevated LVEDP leading to subendocardial necrosis often with normal CKs

WBC: Likely mildly elevated in AMI but may also establish infectious etiology for current state

Hemoglobin: Anemia contributes to patients presenting with shortness of breath or angina

Platelets: Severely depressed <50k levels may be a contraindication to PCI

Electrolytes: Monitor for potassium and calcium abnormalities which may alter the ECG, Evaluate for infectious etiologies, electrolyte abnormalities

contributing to arrhythmias, biliary tract disease, or pancreatitis, if indicated

Creatinine: Usually elevated in patients with longstanding HTN and DM. Elevated creatinine is a relative contraindication to angiography because of the risk of renal failure secondary to contrast nephropathy

LFTs: Elevated in cases of hypotension due to shock or passive congestion due to elevated right-sided filling pressures. Also serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase/aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT/AST) can be elevated from an acute coronary syndrome as it is released from myocardial necrosis

Urine toxicology: Should be obtained for all young or at-risk patients with concerning chest pain (cocaine-induced MI can result from thrombosis in addition to vasospasm and therefore reperfusion may be indicated)

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP): May be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF) (see chapter on complications of AMI)

Should be obtained within 5 minutes of arrival within the emergency department

Make sure to label each ECG with the degree of pain

Comparison to an old ECG can be helpful

Repeat every 15 minutes ×2 if nondiagnostic, this has been shown to increase sensitivity

Dynamic T wave and ST changes should greatly increase your suspicion for ACS

Reoccurrence of CP should be re-evaluated with additional ECG recordings prior to giving NTG

Obtain right-sided leads in those with inferior distribution injury to evaluate for RV injury or infarct

Obtain posterior leads in patients with only anterior ST depression to r/o posterior wall STEMI

Assess for a widened mediastinum and always consider aortic dissection

Examine lung fields for evidence of a pneumonic process, pulmonary congestion, or pneumothorax

Assess ribs and soft tissues for evidence of trauma

Hypoxia/tachypnea with a clear CXR? Consider PE

Useful test for evaluating systolic function, regional WMAs, effusion, valvular lesions, and to assess for complications of MI

May be helpful in a high risk patient with ongoing CP and a nondiagnostic ECG or when the diagnosis of STEMI is in doubt

Used to assess for proximal PE and aortic dissection and to assess for other noncardiac etiologies of CP such as pneumonia or pulmonary mass

Sensitivity and specificity are institutional and reader dependent

Consider MRI if patient has CRI or is high risk for contrast nephropathy

Different phase of contrast often needed for optimal evaluation of PE and aortic dissection

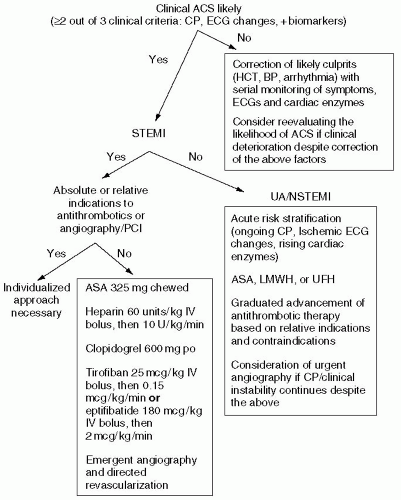

TABLE 3-4 TIMI risk score (TRS) for UA/NSTEMI11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 3-5 UA/NSTEMI ACS risk stratification | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 3-6 Immediate NSTEMI ACS treatment strategies checklist | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree