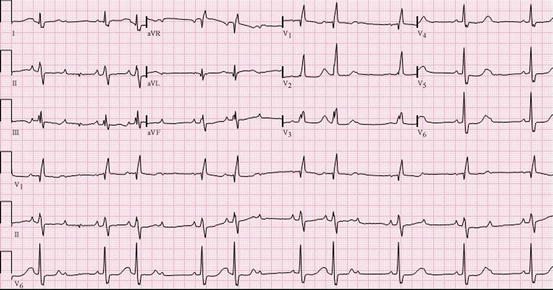

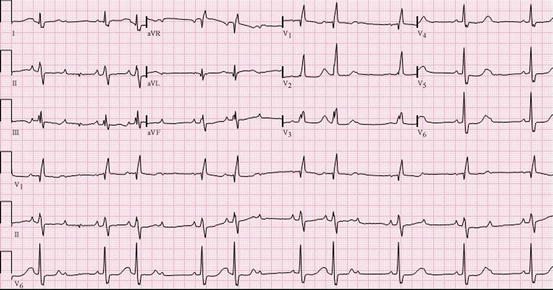

Fig. 14.1

Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrating complete heart block

After the endomyocardial biopsy results returned indicating myocardial sarcoidosis, he was started on prednisone 60 mg daily which was tapered down to 40 mg daily over 2 months, and he was referred to National Jewish Health for evaluation and management of his sarcoidosis. Evaluation at that time included a signal averaged ECG which was abnormal, and an echocardiogram showing LV enlargement with LVEF of 38 %, stage II LV diastolic dysfunction, biatrial enlargement and pacemaker wire in the right ventricle. Appropriate heart failure beta blocker and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapies had previously been initiated, and were up-titrated. It was recommended that the patient have his pacemaker upgraded to an ICD, which was done by his local cardiologist’s office.

Cardiac Sarcoidosis Clinical Vignette #2

A 40-year old woman with a history of progressive shortness of breath and palpitations for 3 months presented with syncope. She was found to have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 40–45 % with inferoseptal hypokinesis and mild right ventricular enlargement. ECG demonstrated an incomplete right bundle branch block. Coronary angiography demonstrated no significant coronary artery disease, and chest radiograph demonstrated small left-sided pleural effusion and mild pulmonary vascular congestion.

Holter monitoring demonstrated runs of non-sustained left bundle branch morphology ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 14.2). The diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy was considered. She underwent a cardiac MRI and was found with delayed gadolinium enhancement of the inferoseptal wall and normal right ventricular size and function. Chest CT demonstrated no hilar lymphadenopathy. Endomyocardial biopsy was then performed, with attempts to obtain samples in the region of delayed gadolinium enhancement and guided by electroanatomic mapping (Fig. 14.3). Pathology demonstrated non-caseating granulomas, and a diagnosis of sarcoidosis was confirmed.

Fig. 14.2

Rhythm strip demonstrating a run of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

Fig. 14.3

(a) and (b) Representative examples of gross granulomatous myocardial scarring and microscopic noncaseating granuloma infiltrating myocardium (c) Low-amplitude intracardiac electrogram at an involved site (d) Electroanatomic map demonstrating reduced voltage corresponding to areas of myocardial scar caused by sarcoid granuloma

She was started on high dose corticosteroids. The patient had a recurrent syncopal episode, and ECG at that time demonstrated Mobitz type 2 second-degree AV block (Fig. 14.4). An ICD/pacemaker was implanted as a result. Three months later, repeat echocardiogram showed improvement in ejection fraction to 55–60 %, and as she had no recurrent arrhythmia or heart block on repeat cardiac monitoring, a slow taper in steroid dose was started.

Fig. 14.4

ECG at that time demonstrated Mobitz type 2 second-degree AV block

Cardiac Sarcoidosis Clinical Vignette #3

The patient is a 60-year-old white man with a history of biopsy-proven pulmonary sarcoidosis from 5 years ago, which initially manifested with shortness of breath and pleurisy that resulted in chest imaging leading to biopsy. He had a history of pericardial effusion with his bout of pleurisy that was self-limited and resolved on its own. He had a past medical history significant for dyslipidemia, nephrolithiasis, and borderline enlarged aorta, and incidental coronary calcification seen on chest computed tomography (CT). He was being treated by a colleague in pulmonary medicine with hydroxychloroquine and prednisone intermittently with some success.

His family history was significant for extensive for coronary disease. His mother died at age 47 from lymphoma/cancer. A maternal grandfather died at age 58 from a myocardial infarction, two maternal uncles were affected by heart disease; one died at age 70 from a myocardial infarction and one is alive at age 83 with his first myocardial infarction in his 60s. His father was deceased, dying at age 69 from a myocardial infarction, and the patient’s older brother was a questionable blue baby with “congenital heart disease”, likely a significant atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect per the description – the patient wasn’t entirely sure.

The patient’s major complaint was shortness of breath resulting in limitations in some of the things he enjoyed doing, in addition to chest tightness he occasionally noticed when going to the gym to exercise. It would come on with activity and resolve with rest usually within 4–5 min. These symptoms persisted despite prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

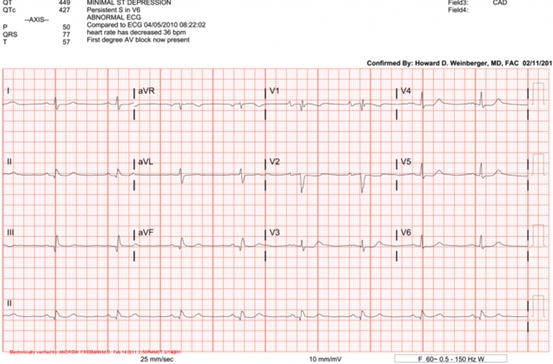

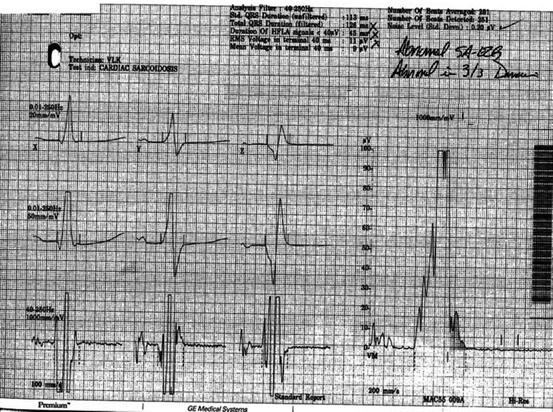

His ECG in the office showed first-degree atrio-ventricular (AV) block and non-specific ST-T wave abnormalities (Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

ECG demonstrating first degree AV block

His cardiac exam, much to his physicians’ surprise, was largely unremarkable.

As a result of his symptoms, a stress test was arranged which demonstrated transient ST elevations in the inferior leads. In addition, in recovery he had ST depressions, which persisted for several minutes and then resolved with slower heart rates. These findings resulted in the patient being sent, by ambulance, to the nearest hospital where a coronary angiogram and catheterization were performed.

The catheterization showed a 50–70 % left anterior descending (LAD) artery stenosis, his second obtuse marginal (OM2) artery with a 70 % occlusion, his first obtuse marginal (OM1) artery with an 80 % occlusion, the left circumflex (LCx) artery distal total occlusion and a chronic total occlusion of his right coronary artery (RCA), receiving collaterals from the LCx.

Interestingly, his echocardiogram remained normal with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, no pericardial effusion, and normal right ventricular function with normal estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressures.

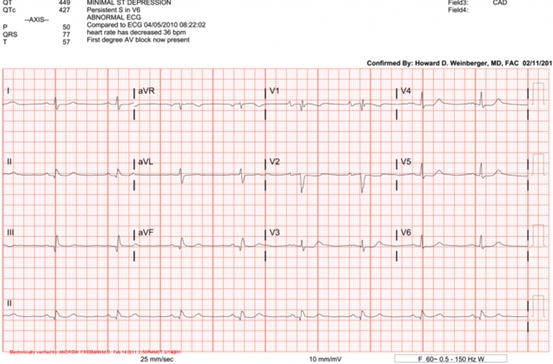

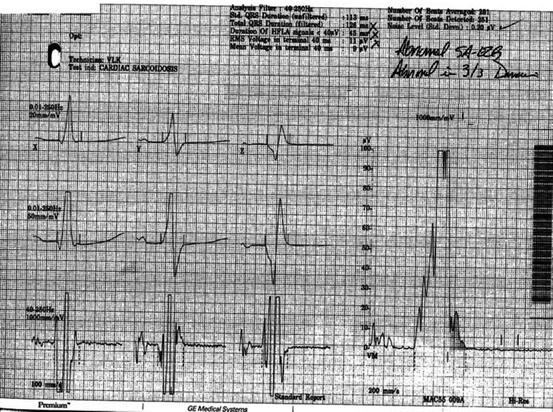

His signal averaged ECG, however, remained abnormal in three out of three domains throughout his therapy (Fig. 14.6).

Fig. 14.6

Signal averaged ECG demonstrating three out of three abnormal domains

Advanced imaging with cardiac MRI was surprisingly without areas of delayed contrast hyperenhancement, though 18-FDG myocardial PET did show some patchiness suggesting areas of inflammation (Fig. 14.7, 14.8, and 14.9).

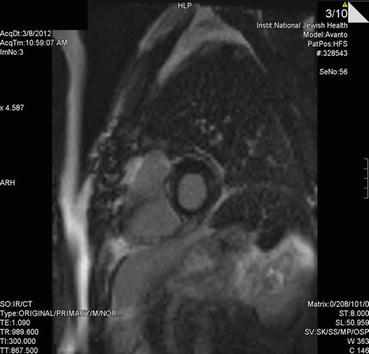

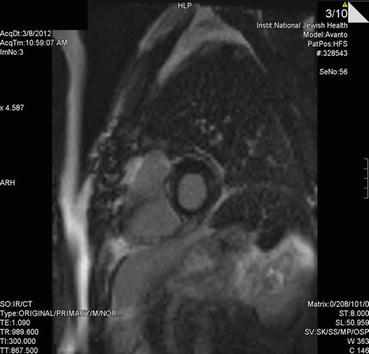

Fig. 14.7

Cardiac MRI delayed contrast enhancement image (vertical long axis) demonstrating no clear focal enhancement

Fig. 14.8

Cardiac MRI delayed contrast enhancement image (short axis) demonstrating no clear focal enhancement

Fig. 14.9

18-FDG myocardial PET demonstrating patchy on diffuse hypermetabolic activity suggesting active inflammation. Note myocardial and likely pericardial involvement

At this point, the decision was made to perform coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), but because of a densely adherent pericardium, only a left internal mammary artery (LIMA) to left anterior descending (LAD) artery bypass could be performed. Subsequently, he received a stent to his left circumflex (LCx) artery which completed the revascularization as best as was possible.

These interventions resulted in him feeling better, but shortly after surgery he developed volume overload and required intensive diuresis.

Just when things appeared to be settling down for this patient, he had an episode of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with heart rates >160 bpm resulting in another emergency room visit with a diagnosis of atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT). He underwent an ablation (and a concurrent right ventricular voltage map and programmed electrical stimulation study which was negative for inducible ventricular tachycardia).

Once all of the above issues were settled, the patient went on vacation to Florida (USA) and played golf for an extended period of time in the heat of the Florida summer. As he was also on a statin with his intensive coronary disease, his urine turned red in color prompting another emergency room visit for mild rhabdomyolysis that resolved with hydration and discontinuation of the statin.

Eventually, the patient’s condition returned to normal and he has been successful at improving his lifestyle, diet, and exercise and has tolerated low dose statins without much trouble.

Interesting Points

1.

Cardiac sarcoidosis can present with normal heart function, but still have pericardial involvement with rhythm disturbances, including first degree AV block.

2.

Cardiac MRI did not show evidence for scarring with delayed contrast hyperenhancement, but, 18-FDG myocardial PET did show patchy inflammation on top of overall inflammation.

3.

While an echocardiogram did not show any abnormalities, an abnormal signal-averaged ECG raised a strong possibility for cardiac sarcoidosis early on in the case.

4.

Pericardial involvement is uncommon even in the presence of extensive myocardial infiltration. It is observed in fewer than 10 % of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, and these patients usually remain asymptomatic [1].

5.

Small pericardial effusions detected by echocardiography were found in 19 % of patients with sarcoidosis [2].

Cardiac Sarcoidosis Clinical Vignette #4

A 75 year old Japanese woman diagnosed with sarcoidosis 21 years previously with skin and eye involvement treated with local and topical steroids. Two years after her diagnosis of sarcoidosis, she suffered a sudden cardiac arrest event but was successfully resuscitated by emergency medical services. An automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) was implanted and she has been well since then.

Two years previously, she began to complain of a vibrating and fluttering sensation in her chest and interrogation of her AICD revealed several appropriate anti-tachycardia pacing interventions by her AICD for ventricular tachycardia in the past 2–3 months. She was subsequently referred to our granuloma clinic for further assessment and management of potential active sarcoidosis myocarditis. Her cardiac medications at the time of presentation included sotaolol, losartan and aspirin. Her initial physical exam revealed stable vital signs and overall unremarkable physical exam.

Initial workup included the following:

Twelve lead ECG: Sinus rhythm, rate of 67, normal axis, interventricular conduction delay with nonspecific ST and T-wave changes.

Echocardiogram: Normal left ventricular size and wall thickness with mildly reduced overall systolic function, estimated left ventricular ejection fraction 40–50 %. Basal infero-septal and posterior wall thinning with akinesis.

She was subsequently started on prednisone at 20 mg daily for 2 months followed by a slow tapering schedule over the next 4 months, and concomitant oral methotrexate starting at 7.5 mg weekly up-titrated gradually to a maintenance dose of 15 mg weekly with folic acid supplementation on a daily basis. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging could not be performed due to the AICD.

On follow up and since starting her immunosuppressive regimens, she has had one to two arrhythmic events that did not require any intervention by her AICD. Her echocardiogram remained stable without change in her LV function, LVEF or wall motion abnormalities. She is currently maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly, has not required any interventions from her AICD and has not required any ablation procedures. Her cardiac medications remained stable throughout her course.

Interesting Points

This case highlights the potential causes of new or worsening arrhythmias in patients with known cardiac sarcoidosis. New or worsening arrhythmias can develop either due to active granulomatous myocarditis or due to scar formation (new or pre-existing). Arrhythmias due to active myocarditis are usually responsive to immunosuppressive therapy and the preferred agent is corticosteroids due to its rapid onset. The ideal dose is not exactly known but based on available literature [3] and expert consensus [4] a dose of 30–40 mg of prednisone daily (or equivalent) is usually recommended. Our case demonstrated a rapid improvement and resolution of her arrhythmias with immunosuppressive therapy and she did not require ablative therapy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree