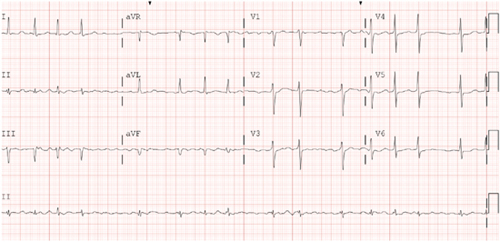

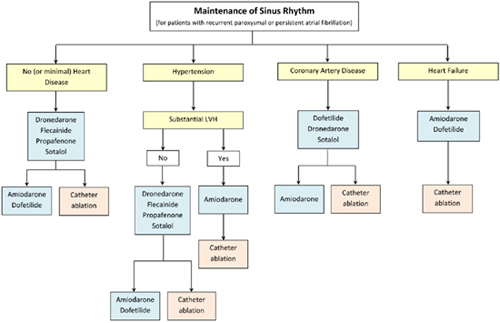

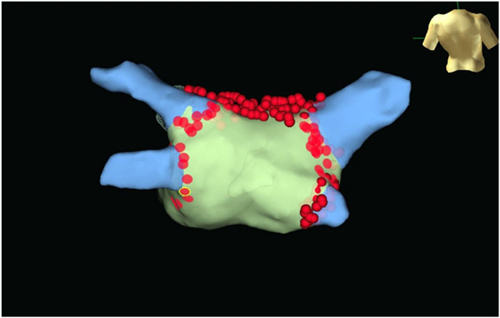

CHAPTER 16 Mustafa M. Dohadwala, MD, and Cynthia Enright, NP Mr. G is a pleasant 57-year-old male with history of hypertension and diabetes whom we saw in the electrophysiology clinic in mid-2013. He presented with palpitations and dyspnea on exertion and was found to be in atrial fibrillation (AF) with ventricular rate of ~100 beats per minute (bpm) for an unknown period of time (Figure 16.1). His past medical history otherwise included hypertension and diabetes for which he was taking amlodipine and metformin. Electrocardiogram upon initial visit demonstrating AF. On examination, he was afebrile with heart rate of 124 bpm, blood pressure of 103/67, and 97% O2 saturation on room air. He was dyspneic after walking from the clinic waiting room to the examination room but did not require accessory muscle use. His right jugular vein was just above the clavicle when at 45° angle. On cardiac auscultation, he was irregularly irregular and tachycardic with normal S1/S2 and no extra heart sounds. His lungs had sparse crackles at the bases. His liver was normal span and he did not have any hepatojugular reflux. His abdomen was nondistended and had normal bowel sounds. His lower extremities were warm to palpation and had 2+ dorsalis pedis pulses. A pharmacologic stress test showed no ischemia or infarct. Echocardiography revealed EF of 35% in the setting of AF with no valvular abnormalities. Given a likely duration greater than 7 days, he was categorized as having persistent AF. As part of the work-up to identify any cause for the AF or coexistent conditions, thyroid testing, electrolytes, renal function, and chest plain films were attained. Laboratory testing was found to be within normal limits and plain films demonstrated mild cardiomegaly. We discussed with him at length the major reasons AF can be problematic, including: (1) risk of stroke; (2) depressed ejection fraction in the setting of prolonged AF with rapid ventricular rates, that is, “tachymyopathy;” and (3) symptoms such as palpitations, dyspnea, chest pain, and so on. We compared his risk of stroke to his risk of bleeding to help guide anticoagulation. His CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc score were both 2, placing him at a low-intermediate risk of stroke. Although his HAS-BLED score of 0 and ATRIA score of 0 suggested low risk of bleeding, he works in construction. After having a balanced discussion with the patient, warfarin for a goal INR 2 to 3 was initiated. Because of his dyspnea in AF with relatively well-controlled rate on ECG, we pursued a rhythm-control strategy. Typically, direct-current cardioversion is chosen rather than pharmacologic cardioversion with medications such as ibutilide owing to lower likelihood of proarrhythmia and higher likelihood of success. Because he was in AF for > 48 hours and had not been anticoagulated, he required transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) just prior to cardioversion. Thus, one week after our clinic visit, he underwent TEE under conscious sedation, which showed no left atrial (LA) or left atrial appendage (LAA) thrombus. Left ventricle (LV) ejection fraction slightly improved to 45%. Subsequently, the anesthesiologist provided deep sedation with propofol. Paddles lined with gauze dampened with saline were positioned along the right parasternal space and apex to encompass the heart. He was cardioverted with 200 J synchronized energy into sinus rhythm (SR). To assist in maintenance of SR, we elected to start antiarrhythmics. There are several antiarrhythmics available to consider (Figure 16.2). Class IC antiarrhythmics such as flecainide and propafenone cannot be used if there is any structural heart disease, heart failure, or coronary artery disease. Class III antiarrhythmics such as dofetilide and sotalol are useful, as they can be used with heart failure, but QTc must be monitored closely due to risk of torsades de pointes. Dofetilide can only be initiated in the hospital setting. Both are renally cleared and dosed depending on creatinine clearance. Amiodarone can be quite effective, but long-term toxicities limit its use, especially in younger patients. Because Mr. G had normal creatinine clearance and did not want to be hospitalized, he was started on sotalol 80 mg twice daily. Antiarrhythmic drug selection for patients with AF. He felt much better in SR on sotalol and followed up in clinic with the electrophysiology attending and electrophysiology nurse practitioner. Unfortunately, several weeks later, he began having frequent, sustained recurrences of AF. Because he was on warfarin with weekly INRs > 2, he was able to be cardioverted without repeat TEE. Sotalol was uptitrated to 160 mg twice daily. Because of the inability to maintain SR despite use of at least one antiarrhythmic, he was taken for an AF ablation. He underwent pulmonary vein isolation to affect the triggers of AF and linear roof line to affect the substrate of AF. The radiofrequency lesions performed in the left atrium are shown in Figure 16.4. Radiofrequency lesions performed in the left atrium are demonstrated with wide area circumferential lesions around both right and left pulmonary veins and a line across the LA roof. Three-dimensional anatomic map with lesion set for pulmonary vein isolation and roof line. Both entrance and exit block were confirmed for pulmonary vein isolation. Bidirectional block was confirmed across roof line. He returned to us in clinic at 4 weeks and 12 weeks, where he reported no symptomatic recurrences. As he works in construction, he asked for his anticoagulation to be discontinued. As providers taking care of patients with AF, we all recognize the risk of stroke, which leads to morbidity and mortality. AF is both a direct cause of stroke and a marker of risk, as a “bystander.” As a direct cause, AF leads to stasis within the LAA where clots form. The risk of thrombus, however, can extend into SR as well.1,2 In some patients, there may be reduced atrial function in SR and an inflammatory state3 that is prothrombotic. Moreover, patients with AF may have coexistent risk factors for stroke due to atherosclerosis of the cerebrovasculature or thoracic aorta that can play a major role. The risk of stroke in AF is not uniform and is informed by various clinical factors. The CHADS2 and, more recently, the CHA2DS2VASc scoring system provide a basis for risk stratification. Those without any risk factors may or may not be treated with aspirin. Those with a score of 1 can receive aspirin or oral anticoagulation. Those with scores ≥ 2 should receive oral anticoagulation. The burden of AF (i.e., “how much”) and not just its sole presence may also play a role in risk assessment. In patients with AF who had pacemakers for bradycardia, risk of stroke increased with episodes greater than one day.4 Another study in 2009 suggested risk of stroke with AF doubled with a burden of AF greater than 5.5 hours per month. With AF less than this amount, the risk of stroke was not higher than those without AF.5 In a study of prospectively evaluated patients greater than age 65 without preexisting AF who were implanted with pacemakers or defibrillators, more than one-third developed atrial tachyarrhythmias within 2.5 years of follow-up. Asymptomatic events were 8× as frequent as symptomatic events. Any amount of AF burden increased risk of stroke compared with those without AF. However, it did appear that more AF versus less AF was related to more events.6 The main therapy for stroke prevention remains anticoagulation, but its use has been long recognized to be dangerous. Fihn et al.7

Case Study: Should All Patients Be Anticoagulated after Ablation for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation?

CASE INTRODUCTION

EARLY MANAGEMENT OF PERSISTENT AF

FAILURE OF ANTIARRHYTHMIC

DOES THE AMOUNT OF AF CHANGE STROKE RISK?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree