Case 23

QUESTIONS

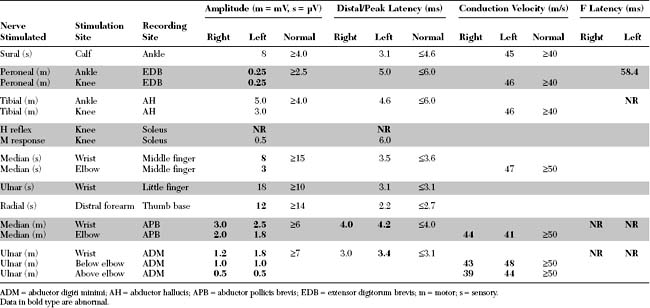

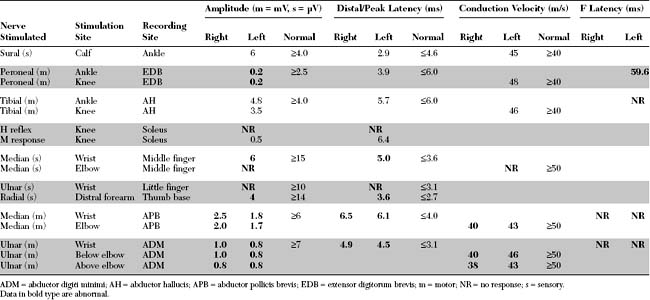

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

DISCUSSION

Rapidly Progressive Quadriparesis: Differential Diagnosis

Quadriparesis progressing over days to weeks is a relatively common neurological presentation. Usually, the history is one of an ascending paresis beginning in the lower limbs and progressing cephalad to trunk and upper limb muscles, and often weakening the respiratory, bulbar, and ocular muscles. Descending weakness, progressing in the opposite direction, may occur but is less common. Causes of nontraumatic rapidly progressive quadriparesis are best discussed using the neuraxis as an anatomical guideline. Since many of the disorders manifesting this presentation are due to lower motor neuron dysfunction, it is useful to use the different elements of the motor unit as a tool in setting a complete differential diagnosis (Table C23-1).

Table C23-1 Causes of Rapidly Progressive Quadriparesis

Adapted from Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC et al., eds. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002.

Certain clinical features and diagnostic studies are useful in establishing the correct diagnosis:

Clinical Features

Typically, GBS develops over the course of a few days. Limb weakness appears simultaneously with a slight tingling and impairment of sensation in the hands and feet. The sensory symptoms are rarely painful while myalgia and back pain are common. Weakness usually ascends from the lower limbs to the upper limbs and, sometimes, to the cranial nerves. Less commonly, the weakness in GBS is descending. Facial weakness occurs in approximately one half of patients, and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation occurs in one-third. Typically, progression lasts up to 4 weeks, while progression exceeding 4 weeks suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). Cerebrospinal fluid protein usually rises during the second week of illness, without pleocytosis (albuminocytologic dissociation). The presence of CSF pleocytosis is not incompatible with GBS, but if it is significant (>50 cells), other diagnoses, particularly infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), should be suspected. The frequency of various GBS manifestations is shown in Table C23-2.

Table C23-2 Frequency of Features and Clinical Variants of Acute Guillain-Barré Syndrome

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Condition | Initially | In Fully Developed Illness |

| Features of Syndrome | ||

| Paresthesias | 70 | 85 |

| Weakness | ||

| Arms | 20 | 90 |

| Legs | 60 | 95 |

| Face | 35 | 60 |

| Oropharynx | 25 | 50 |

| Ophthalmoparesis | 5 | 15 |

| Sphincter dysfunction | 15 | 5 |

| Ataxia | 10 | 15 |

| Areflexia | 75 | 90 |

| Pain | 25 | 30 |

| Sensory loss | 40 | 75 |

| Respiratory failure | 10 | 30 |

| CSF protein >0.55 g/L | 50 | 90 |

| Abnormal electrophysiologic findings | 95 | 99 |

| Clinical variants* | ||

| Fisher syndrome | 5 | |

| Weakness without paresthesias or sensory loss | 3 | |

| Pharyngeal-cervical-brachial weakness | 3 | |

| Paraparesis | 2 | |

| Facial paresis with paresthesias | 1 | |

| Pure ataxia | 1 | |

* Variants are associated with diminished reflexes, demyelinating features as detected on electrophysiologic studies, and elevated cerebrospinal concentrations of fluid protein. Frequencies shown are those found in fully developed illness.

From Ropper AH. The Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1130–1136, with permission.

Because of its similarity to its animal analogue, experimental allergic neuritis, GBS was considered to be a single disorder characterized by an acute immune attack on myelin, hence the term acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP). As the name implies, AIDP is characterized by prominent demyelination and inflammatory infiltrates in the spinal roots and nerves. Criteria for the diagnosis of GBS are based on the AIDP prototype and include both clinical and laboratory findings (Table C23-3). Until recently, AIDP had been used interchangeably with GBS. However, it is now well recognized that axonal forms of GBS exist. Several studies during the last two decades have documented that, although most cases of GBS are characterized by segmental demyelination, many patients with typical GBS have evidence of primary axonal degeneration (“axonal” GBS). GBS may be due to a pure motor axonopathy, named acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), or a mixed sensorimotor axonopathies, named acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) (Table C23-4). In addition to their electrophysiologic characteristics, the subtypes of GBS have characteristic pathological findings, with evidence of vesicular demyelination in AIDP and axonal phagocytosis in AMAN and AMSAN. Also, there is a strong association between GBS, particularly the AMAN form, with a preceding Campylobacter jejuni infection and the presence of serum antibodies directed toward ganglioside M1 (anti-GM1).

Table C23-3 Diagnostic Criteria for Guillain-Barré Syndrome (Mainly Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|