Case 19

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

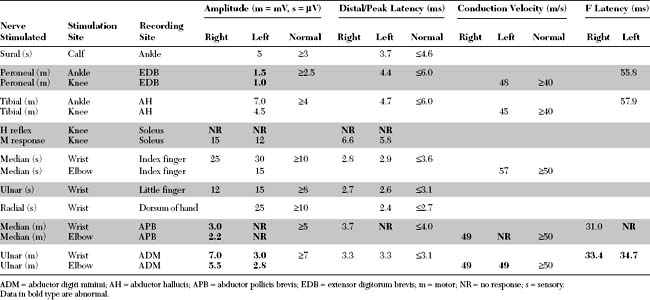

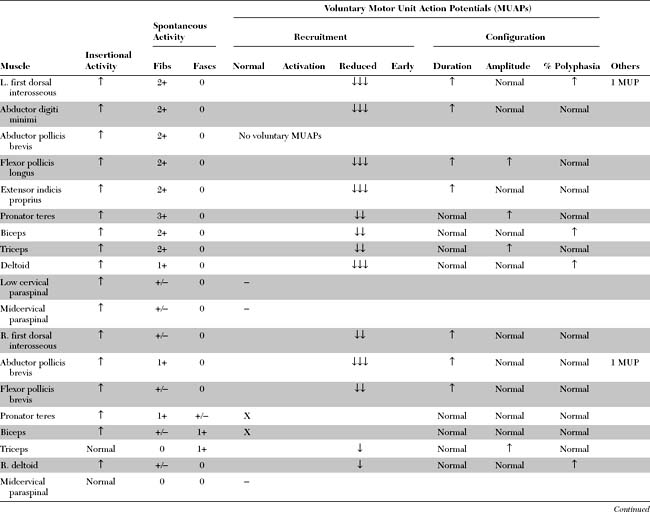

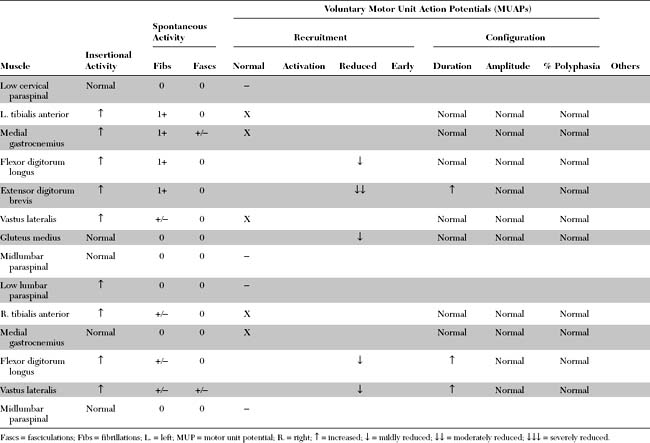

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Pertinent EDX findings in this patient include:

DISCUSSION

Pathology and Etiology

The pathology of sporadic ALS is represented by the selective loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord and brain stem, and cortical motor neurons (Betz cells). Classic findings on spinal cord sections include the loss of anterior horns, with degeneration of the pyramidal tracts (crossed and uncrossed) and dramatic preservation of the dorsal columns and spinocerebellar tracts. Although all motor neurons ultimately degenerate, there is relative sparing of the oculomotor nuclei in the brain stem and Onuff nucleus in the lumbosacral cord. Microscopically, there is, in addition to the loss of anterior horn motor neurons, frequent accumulation of neurofilaments in surviving neurons and dilatation of axons (“spheroids”). The pathologic findings in familial ALS are identical to those in the sporadic form, except that Lewy-like bodies frequently are identified in surviving motor neurons.

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of ALS is based on the presence of a progressive disorder with the characteristic combination of upper and lower motor neuron involvement. Many criteria have been proposed but most are inadequate, particularly those pertaining to early diagnosis and the definition of upper motor neuron involvement. Among them, the revised El Escorial diagnostic criteria currently are the most widely accepted for the diagnosis of ALS (Table C19-1).

Table C19-1 Revised El-Escorial Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|