Another reason for Scheele’s somewhat nebulous reputation is that he was rather self-effacing and worked in comparative obscurity as a pharmacist in Sweden. Added to this, his only book was not as accessible as the accounts of Priestley and Lavoisier. Having said this, Scheele had an extraordinarily productive research career with not only oxygen but many other chemical discoveries to his credit.

Consistent with the comments above, Scheele has not attracted anything like the attention that writers have given to Priestley and Lavoisier. However in 1892, A.E. Nordenskiöld published (in German) a comprehensive selection of the letters and notes of Scheele. This was a pioneering work because little attention had been given to Scheele’s work since his death in 1786. Dobbin [16] published an English translation of collected papers of Scheele including his major book “Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer” (Chemical treatise on air and fire) and a modern reprint is available as indicated in the list of references. Boklund [2] wrote a book on “Carl Wilhelm Scheele: His work and life” which contains a lengthy commentary on some of Scheele’s papers including those in the so-called Brown Book which are almost undecipherable and were omitted by Nordenskiöld. An attractive profusely illustrated volume titled “The Apothecary Chemist: Carl Wilhelm Scheele” was written by Urdang [18] who was director of the American Institute of the History of Pharmacy. This contains a very readable introduction to Scheele’s life and work. Other good accounts are Frängsmyr [7] and Boklund [3]. An English translation of Scheele’s book “Chemical treatise on air and fire” including front matter not available in Dobbin [16], was made by J.R. Forster in 1780 and is available on the Internet at http://tinyurl.com/mnqp2v9 [14]. Partington [10] is authoritative on Scheele’s chemistry discoveries.

10.2 Brief Biography

Scheele was born in Stralsund, a city in western Pomerania, now part of Germany. However at the time this area was under Swedish jurisdiction. The city is on the Baltic coast about 140 km due south of Malmö. Scheele’s father was a rather unsuccessful brewer and corn-chandler. When Carl was 14 he moved to Gothenburg, Sweden to be an apprentice pharmacist. There he developed an interest in chemistry and apparently carried out experiments late in the night using the chemicals available in the pharmacy. He also read widely including the work of Georg Ernst Stahl (1659–1734) who was one of the main proponents of the phlogiston theory. Later Scheele moved to Malmö where he worked with C.M. Kjellström who had scientific interests. There Scheele also made contact with Anders Retzius who was a prominent chemist at Lund University.

A little later Scheele went to Stockholm to work in another pharmacy, but after two years he moved again, this time to Uppsala which was a celebrated academic center. Here he was the director of the laboratory of a large pharmaceutical company, and he became acquainted with Torbern Bergman(1735–1784) (Fig. 10.2) who was a professor of chemistry at the eminent university there. He was well known for his work on chemical affinities, that is the properties that allow dissimilar chemical species to form compounds. He also contributed to the theory of crystal structure and worked on the crystal structure of some minerals. The uranium crystal, torbernite, is named after him. Bergman asked Scheele to help with a problem involving potassium nitrate and acetic acid and later this study led to the discovery of oxygen (see below). Bergman remained a strong advocate of Scheele and wrote a long introduction to Scheele’s book “Chemical treatise on air and fire”. Bergman later called Scheele his greatest discovery.

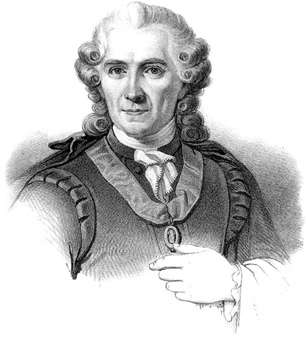

Fig. 10.2

Torbern Bergman (1735–1784). He was an eminent professor of chemistry at Uppsala University and a strong supporter of Scheele all his life. Lithograph by Otto Henrik Wallgren. From (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Torbern_Bergman-1849.jpg)

After five years in Uppsala, Scheele moved to Köping, a small town to the west of Stockholm, where he set up his own business as a pharmacist (Fig. 10.3). Much of his extensive research was done in this somewhat isolated setting. In fact, although the building shown in Fig. 10.3 looks modest, most of Scheele’s chemical research was actually done in a wooden barn in the courtyard behind the house. However his abilities were recognized and he was elected as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Scheele died at the comparatively early age of 43 and it is thought that his habit of tasting various dangerous chemicals may have been a factor in his demise (see below).

Fig. 10.3

Building of the pharmacy in Köping where Scheele did much of his later research. His laboratory was a wooden barn in the courtyard behind the house. From [18]

10.3 The Discovery of Oxygen

As indicated above, Scheele’s studies that eventually resulted in the discovery of oxygen began when he was at Uppsala and he was asked by Torbern Bergman to clarify a problem that occurred when saltpeter (potassium nitrate) was heated with acetic acid and then produced a red vapor which was nitrogen dioxide. Apparently Bergman asked Scheele’s advice because he was concerned about the purity of the saltpeter. When we start to track the events that led up to the discovery of oxygen at this time, a serious problem is that the information about Scheele’s actual experiments comes only from notes and letters. These were subsequently published in German by Nordenskiöld [15] and an English translation of some of this material is available [16]. The fact that Scheele’s work was only described in notes at this stage, some of which are difficult to decipher, makes the identification of the timeline for the discovery of oxygen challenging.

According to Partington [10], Nordenskiöld concluded from his study of the manuscripts that most of the work was completed in 1773, but some of the experiments, including the preparation of oxygen by heating potassium nitrate go back to 1770. Other authors claim that in the earliest experiments, oxygen was produced by heating manganese dioxide with sulfuric acid [4]. “Vitriol air” is an early term that was used by Scheele for oxygen, and this occurs in a manuscript referred to as number 52 from the Uppsala period with dates of 1770–1771.

Scheele produced oxygen by heating a variety of substances including mercuric oxide as did Priestley. Scheele also obtained the gas by heating potassium nitrate, silver carbonate, manganese nitrate and manganese oxide. He reported that the resulting gas was odorless, tasteless, and supported the combustion of a candle more than air. Figure 10.4 reproduces his account from his book (see below) which is here given in an English translation [14]. In a summary of Scheele’s experiments written by Bergman in 1775, he stated that the gas formed by heating oxides of mercury, silver and gold supported both combustion and respiration better than common air [10]. Scheele’s later name for oxygen, “Feuerluft” (fire-air) was first used in 1775.

Fig. 10.4

Extract from the English translation of “Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer”. Note that when Scheele put a burning candle into his fire air it burnt with a flame so vivid that it dazzled the eyes. From [14]

It is therefore clear that Scheele’s first experiments occurred two or three years before Priestley first produced oxygen because his date is well established [5]. His famous account reads “On 1st of August, 1774, I endeavored to extract air from mercurius calcinatus per se [mercuric oxide], and I presently found that… air was expelled from it very readily… but what surprized me more than I can well express, was, that a candle burned in this air with a remarkably vigorous flame… I was utterly at a loss how to account for it” [12]. Priestley first published his discovery in 1775 [11].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree