Chest discomfort is a common symptom and specific factors will increase or decrease the likelihood of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Noncardiac chest discomfort is usually described as stabbing, pleuritic, positional, reproducible with palpation, or occurring after exertion (rather than during activity). If the pain is depicted as radiating to one or both shoulders or brought on by exertion or mental stress, a cardiac origin consistent with angina must be highly suspected. Clinicians must be aware that, in some patients, chest discomfort due to angina may resolve with further activity due to recruitment of collaterals. So-called “anginal equivalents” include indigestion, belching, and dyspnea. Pain that is immediately relieved by sublingual nitroglycerin may be due to cardiac ischemia or esophageal spasm.

Patients with heart failure should be assigned to a New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Class based on their reported symptoms. Patients can also be classified based on the stage of disease progression using the AHA/ACC Heart Failure Stages (Table 1.2).

1.2 PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Many cardiovascular diseases have commonly associated physical exam findings (Table 1.3). An adequate physical examination can streamline the use of additional diagnostic testing, such as laboratory studies and advanced imaging, and improve patient outcomes.

Table 1.3 Physical Exam Findings and Associated Cardiovascular Disease Pathology. Note that this is not an exhaustive differential diagnosis of each finding.

| Physical exam Findings | Associated conditions |

| Carotid bruit | Carotid artery stenosis or transmitted heart murmur (e.g. aortic stenosis) |

| Femoral bruit | Arteriovenous fistula, peripheral arterial disease |

| Abdominal bruit | Celiac artery stenosis, transmitted heart murmur, renal artery stenosis, transplanted kidney |

| Cyanosis | Pulmonary hypertension |

| Cyanosis that affects the lower extremities | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| Large protruding tongue with parotid enlargement | Amyloid |

| Edema | Heart failure, medications, low albumin |

| Medial ulcers, hyperpigmentation, varicosities | Chronic venous insufficiency |

| Muscular atrophy, absent hair in extremity | Chronic arterial insufficiency |

| Anterior cutaneous venous collaterals | Superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction (or subclavian vein) |

| Kyphosis, lumbar/hip/knee flexion | Ankylosing spondylitis (look for aortic regurgitation) |

| Enlarged tender liver | Heart failure (right-sided) |

| Systolic hepatic pulsations | Severe tricuspid regurgitation |

| Ascites | Right heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, hepatic cirrhosis |

| Palpable abdominal mass | Possible abdominal aortic aneurysm |

1.2.1 Blood Pressure

Proper blood pressure measurement is critical for patient care. A major source of error is using an incorrectly sized cuff, i.e. a cuff that is too small will read an artificially elevated blood pressure, and vice versa. Patients should be at rest for 5–10 minutes prior to measurement, seated with their arms at heart level. If a patient is supine, the arm should be raised on a pillow to the level of the mid-right atrium. The first Korotkoff sound is the systolic pressure and the final sound (when the Korotkoff sounds disappear) is the diastolic pressure.

If there is an auscultatory gap (the Korotkoff sounds disappear soon after the first sound), this first sound still denotes the systolic blood pressure. This is more common in hypertensive, elderly patients, with poor arterial flow in the upper extremities.

Pulsus paradoxus is an accentuated decrease (greater than 10 mm Hg) in systolic pressure with inspiration. The peripheral pulse may also disappear. This finding may indicate pericardial tamponade, severe airway obstruction, COPD, or superior vena cava obstruction. To test for pulsus paradoxus, the blood pressure cuff is inflated above systolic pressure. The cuff is deflated slowly (approximately 2–3 mm Hg per second). The pressure at which the first Korotkoff sound occurs should be noted. Initially, the sounds will be irregular as they vary with respiration (i.e. disappear with inspiration). The pressure at which the sounds become regular should be subtracted from the pressure of the first sound, and if the difference is >10 mm Hg, a pulsus paradoxus is present.

Intra-arterial measurement is generally higher than auscultatory measurement. Blood pressure taken distally at the wrist measures higher systolic pressure and lower diastolic pressure, but there is little change to the mean pressure.

Blood pressure should be measured in both arms; a difference of greater than 10 mm Hg is abnormal (Table 1.4). Blood pressure measured in the legs that is greater than 20 mm Hg higher than arm pressures may indicate peripheral arterial disease (PAD) or severe aortic regurgitation (Hill sign).

Table 1.4 Difference of more than 10 mm Hg of Pressure between the Arms.

| Differential diagnosis if blood pressure between arms is greater than 10mm Hg |

| Normal variant (20% of normal subjects) |

| Subclavian artery disease (atherosclerosis or inflammation) |

| Supravalvular aortic stenosis |

| Aortic coarctation |

| Aortic dissection |

1.2.2 Jugular Venous Pressure

Volume status can be assessed by evaluation of the jugular venous pressure (JVP). The internal jugular vein is preferred because there are no valves and it is directly in line with the superior vena cava and right atrium, but the external jugular vein may be easier to visualize when distended. Generally, the venous pulsations are best appreciated with the patient reclined to 30 degrees. To visualize venous pulsations in a patient who is believed to be volume-overloaded, ask the patient to sit with his/her feet dangling over the side of the bed so that venous blood will pool in the lower extremities. If a patient is hypotensive, the supine position may make it easier to visualize the veins. The venous pulsations can be distinguished from the carotid artery by the waveform (a and v waves, and x and y descents) and biphasic pulsation (Table 1.5). The vein also falls with inspiration and obliterates with gentle pressure.

Table 1.5 Jugular venous waveforms associated with cardiovascular diseases.

| Diagnosis | Waveform | Description |

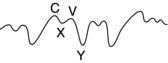

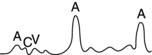

| Normal |  | Positive deflections are a and v waves; c wave is not always seen; refer to text |

| Atrial fibrillation |  | Absent a waves (no regualr atrial contraction) |

| Complete AV block |  | Cannon a waves (atria contracting against closed tricuspid valve) |

| Constrictive pericarditis |  | Accentuated x descent Sharp deep y descent with rapid ascent |

| Tricuspid regurgitation (severe) |  | Prominent v waves (may have single large positive systolic waves with obliteration of the x descent) Rapid deep y descent |

| Tricuspid stenosis |  | Large a wave (increased atrial contraction pressure) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree