70 Cardiovascular Epidemiology

Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Categories of Risk Factors

CHD is a multifactorial disease with multilayered and overlapping “causes” (Box 70-1). More than 300 factors are described as “associated” with CHD. A National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute workshop on cardiovascular risk assessment classified factors implicated in the pathogenesis of a major coronary event into several levels: major atherogenic, plaque burden, conditional, underlying, susceptibility, undetermined, and protective. The multilayered, overlapping paradigm has a variety of mechanisms of action and interactions between levels.

Box 70-1 Categories of Risk Factors for CHD

With permission from Smith Jr SC, Greenland P, Grundy SM. AHA Conference Proceedings. Prevention conference V: Beyond secondary prevention: identifying the high-risk patient for primary prevention: executive summary. American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;101:111–116.

Cardiovascular Risk Prediction: Approaches to Global Risk Assessment

Clinical Importance of Global Estimates for CHD Risk

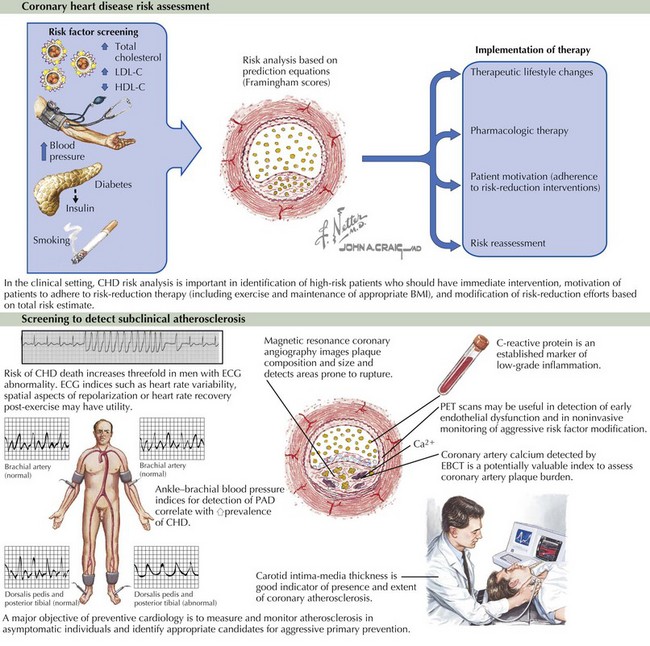

Assessment of global cardiovascular risk based on major cardiovascular risk factors has three purposes of clinical interest: identification of high-risk patients who should have immediate attention and undergo immediate intervention, motivation of patients to adhere to risk-reduction therapies, and modification of the intensity of risk-reduction efforts on the basis of the total risk estimate (Fig. 70-1). Therapeutic decisions based on quantifiable measurements improve clinical decision making, increase motivation and compliance of patients, and can be evaluated for economic planning. Guidelines for management of individual risk factors recommend matching the intensity of preventive therapy to the absolute global cardiovascular risk. Cardiovascular epidemiologic research strives to quantify this global risk via predictive models.

Methods of Risk Assessment

Cardiovascular risk assessment uses two major approaches: simple counting and mathematical models.

Estimating Risk Using the Framingham Risk Scores

Framingham Risk Scores provide two ways to estimate cardiovascular risk.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree