Adult basic life support

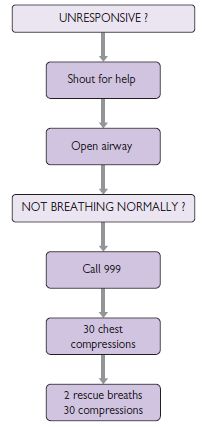

Basic life support (BLS) is the backbone of effective resuscitation following a cardiorespiratory arrest. The aim is to maintain adequate ventilation and circulation until the underlying cause for the arrest can be reversed. 3–4 minutes without adequate perfusion (less if the patient is hypoxic) will lead to irreversible cerebral damage. The usual scenario is an unresponsive patient found by staff, who alert the cardiac arrest team. The initial assessment described below should have already been performed by the person finding the patient. The same person should have also started cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Occasionally you will be the first to discover the patient, and it is important to rapidly assess the patient and begin CPR. The various stages in basic life support are described here and summarized in Fig. 17.1.

1. Assessment of the patient

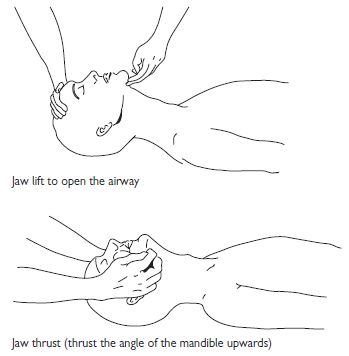

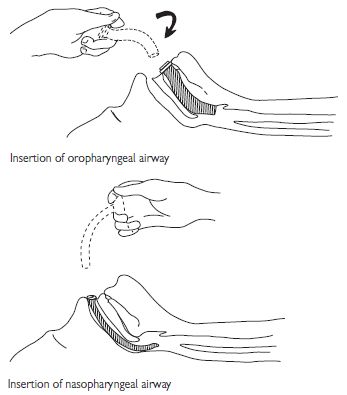

2. Airway assessment

3. Assessment of circulation

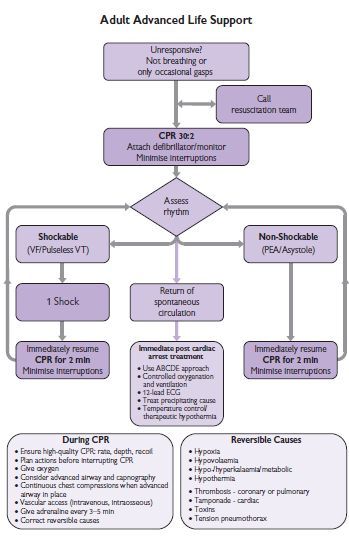

Adult advanced life support

Post-resuscitation care

K+)); arterial blood gases (ABG) (mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis is common and usually responds to adequate oxygenation and ventilation once the circulation is restored; if severe, consider bicarbonate); chest X-ray (CXR; check position of ET tube, look for pneumothorax); urea and electrolytes (U&Es), and glucose.

K+)); arterial blood gases (ABG) (mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis is common and usually responds to adequate oxygenation and ventilation once the circulation is restored; if severe, consider bicarbonate); chest X-ray (CXR; check position of ET tube, look for pneumothorax); urea and electrolytes (U&Es), and glucose.Universal treatment algorithm

Fig. 17.4 The advanced life support 2010 universal algorithm for the management of cardiac arrest in adults. For further information see The Resuscitation Council (UK) website  http://www.resus.org.uk/.

http://www.resus.org.uk/.

VF/VT

Non-VF/VT rhythms

Asystole

PEA

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (see p. 268)

Indication for primary PCI

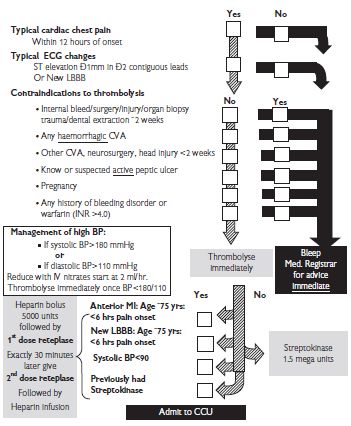

Acute MI: thrombolysis protocol

See Fig. 17.5.

Fig. 17.5 Acute MI: thrombolysis protocol. BP = blood pressure; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; INR = international normalized ratio.

Acute myocardial infarction

| ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) | p. 256 |

| STEMI: diagnosis | p. 258 |

| STEMI: general measures | p. 262 |

| STEMI: reperfusion therapy (thrombolysis) | p. 264 |

| STEMI: reperfusion by primary PCI | p. 268 |

| Rescue PCI | p. 269 |

| STEMI: additional measures | p. 270 |

| Right ventricular (RV) infarction | p. 272 |

| STEMI: predischarge risk stratification | p. 274 |

| STEMI: complications | p. 276 |

| Ventricular septal defect post-MI | p. 278 |

| Acute mitral regurgitation post-MI | p. 280 |

| Pseudoaneurysm and free-wall rupture | p. 281 |

| Cocaine-induced MI | p. 282 |

| Ventricular tachyarrhythmias post-MI | p. 284 |

| Atrial tachyarrhythmia post-MI | p. 284 |

| Bradyarrhythmias and indications for pacing | p. 285 |

| Bradyarrhythmias post-MI | p. 285 |

| Hypotension and shock post-MI | p. 286 |

| Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)/unstable angina (UA) | p. 290 |

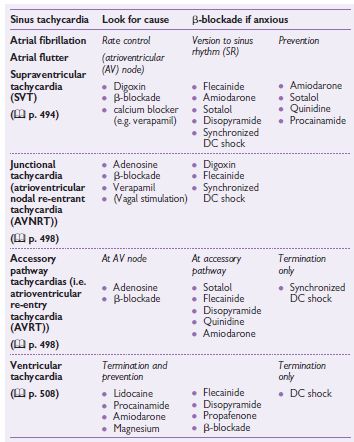

Treatment options in tachyarrhythmias

Ventricular tachycardia: drugs

See Table 17.1.

Table 17.1 Dosages of selected antiarrhythmics for the acute treatment of VT

| Drug | Dosage |

| Magnesium sulphate | Loading dose 8 mmol (2g) IV over 2–15 min (repeat once if necessary) Maintenance dose 60 mmol/48 mL saline at 2–3 mL/h |

| Lidocaine | Loading dose 100 mg IV over 2 min (repeat once if necessary) Maintenance dose 4 mg/min for 30 min 2 mg/min for 2 h 1–2 mg/min for 12–24 h |

| Procainamide | Loading dose 100 mg IV over 2 min Repeat every 5 min to max 1 g Maintenance dose 2–4 mg/min IV infusion 250 mg q6h PO |

| Amiodarone | Loading dose 300 mg IV over 60 min via central line followed by 900 mg IV over 23 h or 200 mg PO tds x 1 week then 200 mg PO bd x 1 week Maintenance dose 200–400 mg od IV or PO |

| Disopyramide | Loading dose 50 mg IV over 5 min repeated every 5 min up to maximum 150 mg IV 200 mg PO Maintenance dose 2–5 mg/min IV infusion 100–200 mg q6h PO |

| Flecainide | Loading dose 2 mg/kg IV over 10 min (max 150 mg) Maintenance dose 1.5 mg/kg IV over 1 hour then 100–250 mcg/kg/h IV for 24 h or 100–200 mg PO bd |

Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias

See Table 17.2.

Table 17.2 Dosages of selected antiarrhythmics for SVT

| Drug | Dosage |

| Digoxin | Loading dose: IV 0.75–1 mg in 50 mL saline over 1–2 h PO 0.5 mg q12h for 2 doses then 0.25 mg q12h for 2 days Maintenance dose: 0.0625–0.25 mg daily (IV or PO) |

| Propranolol | IV 1 mg over 1 min, repeated every 2 min up to maximum 10 mg PO 10–40 mg 3–4 times a day |

| Atenolol | IV 5–10 mg by slow injection PO 25–100 mg daily |

| Sotalol | IV 20–60 mg by slow injection PO 80–160 mg bd |

| Verapamil | IV 5 mg over 2 min; repeated every 5 min up to maximum 20 mg PO 40–120 mg tds |

| Procainamide | IV 100 mg over 2 min; repeated every 5 min up to maximum 1 g PO 250 mg q6h |

| Amiodarone | Loading dose: IV 300 mg over 60 min via central line followed by 900 mg IV over 23 h or PO 200 mg tds x 1 week then 200 mg PO bd x 1 week Maintenance dose: 200–400 mg od IV or PO |

| Disopyramide | IV 50 mg over 5 min; repeated every 5 min up to maximum 150 mg IV 100–200 mg q6h PO |

| Flecainide | 2 mg/kg IV over 10 min (max 150 mg) or 100–200 mg PO bd |

Acute pulmonary oedema: assessment

Presentation

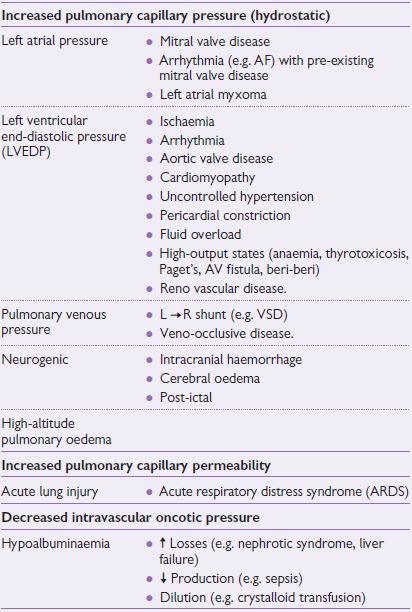

Causes

A diagnosis of pulmonary ooedema or ‘heart failure’ is not adequate. An underlying cause must be sought in order to direct treatment appropriately. Causes may be divided into:

Often there is a combination of factors involved (e.g. pneumonia, hypoxia, cardiac ischaemia); see Drugs for hypertensive emergencies, p. 760.

The main differential diagnosis is acute (infective) exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (previous history, quiet breath sounds ± wheeze, fewer crackles). It may be difficult to differentiate the two clinically.

Principles of management

Initial rapid assessment

Urgent investigations for all patients

| • ECG | • Sinus tachycardia most common |

| • ? any cardiac arrhythmia (atrial fibrillarion (AF), SVT, VT) | |

| • ? evidence of acute ST change (STEMI, NSTEMI, unstable angina (UA)) | |

| • ? evidence of underlying heart disease (left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), p mitrale) | |

| • CXR | • To confirm the diagnosis, looking for interstitial shadowing, enlarged hila, prominent upper lobe vessels, pleural effusion, and Kerley B lines. Cardiomegaly may or may not be present. Also exclude pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus (oligaemic lung fields), and consolidation |

| • ABG | • Typically ↓PaO2. PaCO2 levels may be ↓ (hyperventilation) or  depending on the severity of pulmonary oedema. Pulse oximetry may be inaccurate if peripherally shut down depending on the severity of pulmonary oedema. Pulse oximetry may be inaccurate if peripherally shut down |

| • U&Es | • ? pre-existing renal impairment. Regular K+ measurements (once on IV diuretics) |

| • Full blood count (FBC) | • ? anaemia or leucocytosis, indicating the precipitant |

| • Echocardiography (ECHO) | • As soon as practical to assess LV function, valve abnormalities, ventricular septal defect (VSD), or pericardial effusion |

PaCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood; PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood.

Investigations for patients with pulmonary oedema

All patients should have:

Where appropriate, consider:

Pulmonary oedema: causes

Look for an underlying cause for pulmonary oedema.

Pulmonary oedema: management

Stabilize the patient

If the patient responds arrange appropriate investigations as listed on Acute pulmonary oedema: assessment, p. 724 to help with further management. However, if there is further deterioration, specific measures should be taken to address problems.

Further management

The subsequent management of the patient is aimed at ensuring adequate ventilation/gas exchange and haemodynamic stability and correcting any reversible precipitins of acute pulmonary oedema.

If the patient remains unstable and/or deteriorates, assess their respiratory function.

Assessment of respiratory function

Assess the patient’s haemodynamic status

It is important to distinguish between cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, as further treatment is different between the two groups. This may be difficult clinically. A PA (Swan–Ganz) catheter must be inserted if the patient’s condition will allow.

Management

The general approach involves combination of diuretics, vasodilators ± inotropes. Patients may be divided into two groups:

Patients with systolic BP<100 mmHg

The choice of inotropic agent depends on the clinical condition of the patient and, to some extent, the underlying diagnosis:

Patients with systolic BP ≥100 mmHg

Long-term management

Pulmonary oedema: specific conditions

Diastolic LV dysfunction

Fluid overload

Known (or unknown) renal failure

Anaemia

Hypoproteinaemia

Acute aortic regurgitation

Presentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree