58 Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy

Physiologic Adaptations to Pregnancy

Changes during Pregnancy

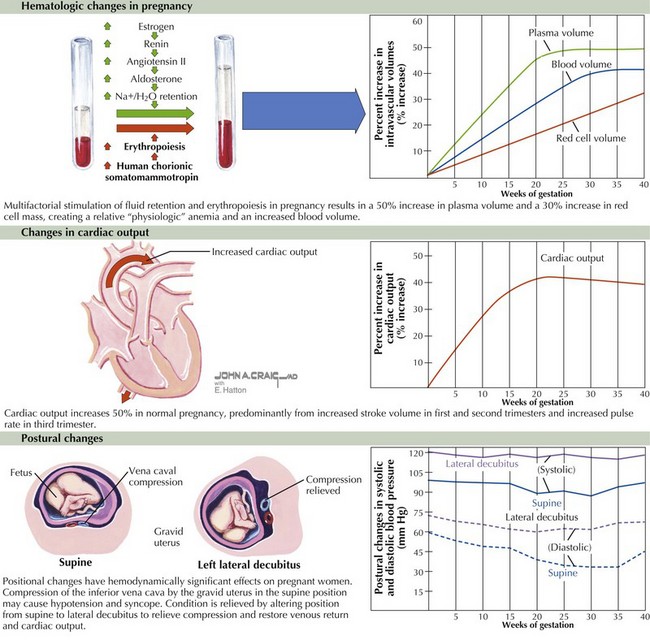

Important hemodynamic changes occur during pregnancy as a result of increases in red blood cell mass and plasma volume. Red blood cell mass typically increases by 20% to 30%, while plasma blood volume can increase even more—generally by about 50%. The etiology of the increase in blood volume is multifactorial and due mainly to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system by estrogen. In addition, other pathways responsible for water retention are stimulated by other pregnancy-related hormones (Fig. 58-1). This relative increase in total blood volume results in a relative anemia, referred to as the physiologic anemia of pregnancy.

Cardiac output increases by approximately 45% during a normal pregnancy, starting as early as 5 weeks after the last menstrual period, predominantly from an increase in stroke volume (during the first and second trimesters) and an increase in heart rate (10–20 bpm during the third trimester). Most of the increase in cardiac output occurs by gestational week 16. This increase is followed by a further, slower increase in cardiac output that peaks at week 24 until week 32. Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) decreases 34% by 20 weeks as a result of decreased aortic compliance and arteriovenous shunting in the uterus. Subsequently, in the final weeks of pregnancy there is a slight decrease in cardiac output that reflects the decrease in stroke volume due to increased SVR (see Fig. 58-1, middle).

Positional changes also have hemodynamically significant effects on the pregnant woman. Of particular importance is the supine hypotension syndrome characterized by symptoms of near-syncope/syncope caused by compression or occlusion of the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus when the pregnant woman lies supine. Symptoms can be relieved by assuming another position, particularly the left lateral decubitus position (see Fig. 58-1, lower). The supine hypotension syndrome is one of the primary reasons to advise pregnant women against exercising in the supine position after the first trimester. This positional effect must also be recognized in the event that a pregnant woman (particularly in the second or third trimester) requires cardiopulmonary resuscitation. If this unfortunate situation arises, the woman should be placed in the left lateral decubitus position.

Clinical Presentation

Cardiac Examination during Normal Pregnancy

The symptoms of normal pregnancy—including fatigue, dyspnea, palpitations, and even near-syncope—in association with the normal signs of pregnancy (including augmentation of the jugular venous pulsations, normal heart sounds or murmurs, and a modest amount of lower extremity edema) may be misinterpreted as those of cardiac disease. Conversely, pathologic signs and symptoms at times may be attributed to normal pregnancy. Thus, knowledge of the normal cardiac examination during pregnancy is crucial (Table 58-1).

Table 58-1 Normal Physical Findings for the Cardiac Examination during Pregnancy

| Examination | Findings |

|---|---|

| Precordial palpation | |

| Heart sounds | |

| Heart murmurs | Diastolic murmurs (rare; soft, medium- to high-pitched), heard best over the pulmonic area and over the left sternal border |

LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular.

Preexisting Disease States and Pregnancy

Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital heart disease is thought to be multifactorial in origin, arising from a genetic predisposition combined with environmental factors. In general, the risk to offspring is modest (~3% to 5%) but much greater than in the general population. It should be noted, however, that reported rates vary between 1% and 18%, depending on the specific type of maternal lesion and the number of affected siblings. Maternal congenital heart disease confers different risks to both the mother and fetus, depending on the type of lesion (Table 58-2).

Table 58-2 Congenital Heart Disease and Maternal and/or Fetal Risk during Pregnancy (Excluding Valvular Disease)

| High Risk | Moderate Risk | Low Risk |

|---|---|---|

• Severe pulmonary hypertension with septal defects (e.g., Eisenmenger’s syndrome) or without septal defects |

LV, left ventricular; NYHA, New York Heart Association; TGA, transposition of the great arteries.