Cardiovascular disease in less-developed countries

Burden of cardiovascular disease in less-developed countries

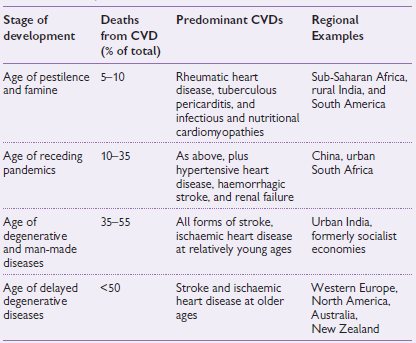

Approximately 80% of the world’s people reside outside Western Europe and Canada/USA. Although cardiovascular diseases (CVD) occur throughout the world, their form and the burden change as a country undergoes economic development. Less-developed countries begin with a disease burden dominated by infectious, perinatal, and nutritional diseases and, in the process of development, make the transition to one dominated by non-communicable disease (NCD), particularly CVD. The four stages of transition are shown in Table 14.1.

Table 14.1 Deaths caused by cardiovascular disease at different stages of development1

1 Howson CP, Reddy KS, Ryan TJ, Bale JR (1998). Control of Cardiovascular Diseases in Less Developed Countries: research, development, and institutional strengthening. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press.

Many less-developed countries have a triple burden of disease, encompassing disorders that characterize the first three phases of the epidemiologic transition.

NCDs rank first in most less-developed countries, in developed countries, and worldwide as a cause of death. CVD accounts for about half of all NCD deaths. In 1990, CVDs were the leading cause of death for all major geographic regions of the developing world except India and sub-Saharan Africa.

There is an early age of CVD deaths in less-developed countries compared to developed countries. In 1990, the proportion of CVD deaths occurring below the age of 70 years was 26.5% in developed countries, compared to 46.7% in less-developed countries. Therefore, the contribution of the less-developed countries to the global burden of CVD, in terms of DALYs lost, was nearly three times higher than that of developed countries.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is the most common cause of CVD in children and young adults in less-developed countries. At least 15.6 million persons are estimated to be to be affected with RHD globally. More than 2 million require repeated hospitalization and 1 million will need heart surgery over the next 20 years. Annually, 233 000 deaths occur as a result of RHD. Many poor persons, who are preferentially affected, are disabled because of lack of access to the expensive medical and surgical care demanded by the disease. The prevalence of RHD in less-developed countries ranges from 20 to 40 per 1000 (by echocardiographic screening of schoolchildren). The incidence of rheumatic fever ranges from 13 to 374 per 100 000, and the rate of recurrence is high.

Managing with limited resources

The management of CVD is often technology intensive and expensive. Procedures for diagnosis or therapy, drugs, hospitalization, and frequent consultations with healthcare providers all contribute to the high cost. The high expenditure on tertiary care in most less-developed countries probably has a large contribution from CVD. This may divert scarce resources from developmental needs and from the unfinished agenda of infectious and nutritional disorders. Thus there is an urgent need for cost-effective preventive strategies and case-management approaches that are based on the best available evidence, and generalized to the context of each developing country.

Infectious disease and the heart

Numerous infectious diseases may involve the endocardium (see Infective endocarditis, Chapter 4, pp. 187–209), myocardium (see Heart muscle diseases, Chapter 8, pp. 417–457), and the pericardium (see Pericardial diseases, Chapter 9, pp. 459–476). This section deals with a miscellaneous group of infectious diseases that are of particular relevance to cardiology practice outside Western Europe, e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, Chagas’ disease, diphtheria, syphilis, and tetanus. Although occasional examples have been reported, myocardial involvement is so rare as to be of little clinical significance in tuberculosis (apart from pericarditis), typhoid fever, scrub typhus, poliomyelitis, infective hepatitis, virus pneumonias, and other respiratory tract infections.

Diphtheria

Cardiac damage in diphtheria is due to a circulating exotoxin that inhibits protein synthesis in target tissues, with a high degree of affinity for the conduction system. Myocarditis occurs in up to 25% of cases of diphtheria and carries a mortality of approximately 60%.

Pathological examination shows a flabby dilated heart with a ‘streaky’ appearance of the myocardium. Microscopy reveals characteristic fatty infiltration of the myocytes, and other features of myocarditis.

Sinus tachycardia, gallop rhythm, cardiomegaly, and hypotension typically appear in the second week of illness.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities are useful in diagnosis and fall under two headings:

The ECG eventually returns to normal but conduction abnormalities may persist for years.

Treatment

Treatment consists of supportive measures for heart failure, antibiotics (procaine penicillin G 600 000 U IM 12 hourly for 10 days or erythromycin 250–500 mg PO 6 hourly for 7 days) to prevent secondary infection and eliminate the diphtheria organisms in the throat, and temporary pacing in cases of AV heart block. Antitoxic serum should not be given at this stage because the exotoxin is already fixed and because of the risk of fatal serum reactions. Intubation and ventilation may be required for those patients with evidence of respiratory failure.

HIV and the cardiovascular system

The clinical effects of HIV on the heart are relatively uncommon, relative to the impact of HIV infection on the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and skin. There are similarities in the pattern of CVD involvement in people living in developed and less-developed countries, but differences in the causative organisms implicated. The main presentations are (1) pericardial effusion; (2) cardiomyopathy; (3) pulmonary hypertension; (4) large vessel aneurysms; and (5) metabolic complications associated with anti-retroviral drug use.

Pericardial effusion

Pericardial effusion is one of the early presenting features of HIV infection in patients living in sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas in western countries, a large effusion is usually idiopathic in 80% of patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), the disease is caused by tuberculosis in over 80% of Africans living with HIV. Purulent pericarditis is not uncommon, while involvement with Kaposi’s sarcoma and B-cell lymphoma is rare. Treatment of tuberculous pericarditis is with a standard anti-tuberculous regime similar to that used in HIV-negative patients, and the short-term outcome is similar. The role of adjuvant steroids is uncertain.

Cardiomyopathy

Cardiomyopathy is found in 50% of acutely ill hospitalized patients, and in 15% of ambulatory asymptomatic patients living with HIV. Myocarditis is present in a proportion of the cases. In western series, the myocarditis is associated with cardiotropic virus, whereas in Africa, preliminary data suggest that it may be associated with non-viral opportunistic infections such as toxoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection. HIV-positive patients with cardiomyopathy should be considered for endomyocardial biopsy to exclude a treatable cause of myocarditis. Otherwise, treat as for heart failure. Prognosis is poor, with a median survival of 100 days without anti-retroviral drugs.

Pulmonary hypertension

HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension is estimated to be 1/200, much higher than the 1/200 000 found in the general population. Primary pulmonary hypertension is found in 0.5% of hospitalized AIDS patients and is a cause of cor pulmonale and death. The pathogenesis is poorly understood.

Arterial aneurysm

Metabolic abnormalities

The use of protease inhibitors and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors is associated with the following metabolic abnormalities: fat redistribution (lipodystrophy), increased total cholesterol and triglycerides, decrease in high-density lipoprotein (HDL), impaired glucose tolerance, and increased intra-abdominal fat. These changes translate into a small increase in the risk of myocardial infarction (MI) with the long-term use of anti-retroviral drugs. It is prudent to modify cardiovascular risk factors and treat the metabolic complications when they arise, according to standard guidelines in affected patients.

Chagas’ disease and the heart

Chagas’ disease is a myocarditis of parasitic origin that is caused by the protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi. The disease is a major public health problem in South and Central America; 15–18 million people are infected with the parasite, and 65 million people are at risk. Chagas’ disease is transmitted by contamination of the bite wound of the ‘assassin’ or ‘kissing’ reduviid bugs with the infected faeces of the insect.

Natural history

The natural history of Chagas’ disease is characterized by three phases: acute, latent, and chronic. Acute Chagas’ disease occurs predominantly in children in less than 10% of infected cases; it is fatal in 10% of cases. It is characterized by fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and facial oedema. Acute myocarditis is common and may be fatal. Rarely, meningoencephalitis or convulsive seizures may occur, sometimes causing permanent mental or physical defects or death. Recovery is usual, however, and the disease is quiescent for the next 10 to 15 years (latent Chagas’ disease). Chronic Chagas’ disease may be asymptomatic, mild, or accompanied by cardiomyopathy, megaoesophagus, and megacolon, with a fatal outcome. The late manifestations probably result from lymphocyte-mediated destruction of muscle tissue and nerve ganglions during the acute stage of the disease. Trypanosoma cruzi may be found in degenerated muscle cells, especially in the right atrium.

The disease is characterized clinically by anginal chest pain, symptomatic conduction system disease; severe, protracted, congestive cardiac failure, often predominantly right sided, is the rule in advanced cases. Bifascicular block is present in more than 80% of cases and death from asystole and arrhythmia is common. Autonomic dysfunction is common. Apical aneurysms and left ventricular dilatation increase the risk of thromboembolism and arrhythmias.

Diagnosis

Chagas’ disease is identified by demonstration of trypanosomes in the peripheral blood or leishmanial forms in a lymph node biopsy, or by animal inoculation or culture, xenodiagnosis (i.e. the patient is bitten by reduviid bugs bred in the laboratory; the subsequent identification of parasites in the intestine of the insect is proof of infection in the human host), or serologic tests (e.g. Machado–Guerreiro complement fixation test). The chest X-ray (CXR) demonstrates cardiomegaly. The ECG is abnormal as a rule in the late course of the disease. The echocardiographic features in advanced cases are those of dilated cardiomyopathy; a left ventricular posterior wall hypokinesis and relatively preserved interventricular septum motion, associated with an apical aneurysm is distinctive. Radionuclide ventriculography may show ventricular wall motion abnormality in the absence of overall depression of global ventricular function. Perfusion scanning with thallium-201 may show fixed defects (corresponding to areas of fibrosis) as well as evidence of reversible ischaemia. Gadolinium-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify patients with more active myocardial disease.

Treatment

There is no specific therapy for Chagas’ disease. Prolonged administration of nifurtimox, a nitrofurazone derivative, may effect parasitologic cure, but chronic organ damage is irreversible. Heart failure, arrhythmias, and thromboembolism are treated with the usual measures.

Prevention

Reduviid bugs, the vectors for Chagas’ disease, inhabit poorly constructed houses and outbuildings. Spraying with 5% γ-benzene hexachloride is most effective in controlling the vector. Patching wall cracks and cementing over dirt floors also helps to eliminate the vectors.

Cardiovascular syphilis

Cardiovascular syphilis produces thoracic aneurysm, narrowing of the coronary ostia, or aortic valvular insufficiency that usually appears 10 to 25 years after the initial infection. Involvement of the myocardium is rare. The introduction of penicillin has made the disease less common, but it remains an important cause of CVD in poor populations.

Coronary disease

Angina pectoris, rarely MI, cardiac aneurysm, or sudden death may result from involvement of the coronary ostia. Aortic insufficiency is nearly always present. The condition should be suspected when angina pectoris is encountered in young men, and when severe angina is associated with disproportionately mild aortic insufficiency. Glyceryl trinitrate is often less effective in relieving symptoms. Attacks of angina decubitus are not infrequent. The diagnosis is established by positive syphilis serology and coronary angiography. Successful surgical treatment may be achieved by endarterectomy of the coronary ostia or by bypass grafting.

Aortic insufficiency

The presenting symptoms may be those of coronary insufficiency or of left heart failure. The physical signs are the same as those of rheumatic aortic insufficiency. Pure insufficiency without any stenosis is the rule. Because of the unfolding and dilatation of the aorta, the murmurs are frequently better heard to the right of the sternum. Occasionally, a musical (‘cooing-dove’) diastolic murmur is produced by eversion or detachment of an aortic cusp.

Syphilitic aortic aneurysm

This involves the ascending aorta and the arch with equal frequency. Less commonly, the descending aorta is involved, and least commonly the abdominal aorta. It is not unusual for the aorta to be involved at more than one site in the same patient. Syphilitic aneurysms are usually saccular (vs. fusiform aneurysms of atherosclerosis). Syphilitic aneurysms can rupture, but never dissect. The clinical presentation is dependent on compression of adjacent structures and therefore varies with the portion of the aorta involved.

Ascending aorta aneurysms have been termed the ‘aneurysms of signs’:

Related

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree