The American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) were developed to guide use of myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (MPS), stress echocardiography, and cardiac computed tomographic angiography (CCTA). To date, cardiologist application of AUC from a patient-based multiprocedure perspective has not been evaluated. A Web-based survey of 15 clinical vignettes spanning a wide spectrum of indications for MPS, STE, and CCTA in coronary artery disease was administered to cardiologists who rated the ordered test as appropriate, inappropriate, or uncertain by AUC application and suggested a preferred alternative imaging procedure, if any. In total 129 cardiologists responded to the survey (mean age 49.5 years, board certification for MPS 65%, echocardiography 39%, CCTA 32%). Cardiologists agreed with published AUC ratings 65% of the time, with differences in all categories (appropriate, 50% vs 53%; inappropriate, 42% vs 20%; uncertain, 9% vs 27%, p <0.0001 for all comparisons). Physician age, practice type, or board certification in MPS or echocardiography had no effect on concordance with AUC ratings, with slightly higher agreement for those board certified in CCTA (68% vs 64%, p = 0.04). Cardiologist procedure preference was positively associated with active clinical interpretation of MPS and CCTA (p = 0.03 for the 2 comparisons) but not for ownership of the respective imaging equipment. In conclusion, cardiologist agreement with published AUC ratings is generally high, although physicians classify more uncertain indications as inappropriate. Active clinical interpretation of a procedure contributes most to increased procedure preference.

Cardiovascular imaging is an important decision-making tool for patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD), but it consumes significant health care resources. To help providers and reimbursement agencies determine a rational approach to use of diagnostic testing, the American College of Cardiology has developed Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) for noninvasive imaging procedures including myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (MPS), stress echocardiography (STE), and cardiac computed tomographic angiography (CCTA). The application of AUC for MPS, STE, and CCTA has been studied in a variety of single-procedure settings and has been found to be reliable, reproducible, and feasible. However, previous investigations have been generally limited to single procedures. We thus performed a Web-based survey using clinical vignettes for MPS, STE, and CCTA to determine the physician performance of AUC application across procedures and physician preference between procedures for noninvasive CAD evaluation.

Methods

All physicians who participated in an e-mail membership list for attendance to a single large cardiac imaging continuing medical education course were invited by e-mail to take part in a Web-based survey from January to February 2011 (30 days), with the raffle of an iPad electronic tablet (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, California) as inducement for survey completion. The survey presented clinical vignettes as exemplars of different major indications for CAD workup common to MPS, STE, and CCTA. Categories of indications and appropriateness ratings for vignettes using MPS, STE, and CCTA were obtained from the 2009, 2008, and 2010 AUCs for each procedure, respectively. Because the new AUC for STE and echocardiography was released in March 2011, enrollment was closed at the end of February to avoid reclassification of vignettes over time.

Only CAD-related indications were chosen for clinical vignettes using MPS, STE, and CCTA and the most commonly applied AUC indications. Vignettes for hypothetical exemplar patients were modeled after clinical patient notes and presentations, with care to include age, gender, CAD risk factors, and symptoms (online Appendix ). We also included pertinent CAD medications, physical examination findings (including blood pressure and heart rate), lipid panels, baseline electrocardiographic findings, ability to exercise, and imaging test ordered. The distribution of indications, procedures, and appropriateness is presented in Table 1 . Physicians were asked to rate each vignette by applying current AUC to a 3-category choice of “appropriate,” “uncertain,” and “inappropriate.” Each vignette was also followed by a choice of what alternative test they would have ordered: MPS, STE, CCTA, no testing, or other (including exercise treadmill testing, cardiac magnetic resonance, positron emission tomographic imaging, and invasive coronary angiography).

| Description of Indication | AUC Rating | Physician Rating (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 129) | ||||

| I | U | A | ||

| Myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomographic representative vignettes | 43.0 | 8.8 | 48.3 | |

| Asymptomatic, intermediate coronary heart disease risk (Adult Treatment Panel III risk criteria), electrocardiogram interpretable | I ⁎ | 51 ⁎ | 10 | 39 |

| Evaluation of ischemic equivalent (nonacute): low pretest probability of coronary artery disease, electrocardiogram interpretable, and able to exercise | I ⁎ | 58 ⁎ | 12 | 30 |

| Risk assessment after revascularization, asymptomatic, and ≥2 years after percutaneous coronary intervention | U ⁎ | 43 | 10 ⁎ | 47 |

| Risk assessment after revascularization, evaluation of ischemic equivalent | A ⁎ | 10 | 2 | 88 ⁎ |

| Risk assessment after revascularization, asymptomatic, <5 years after coronary artery bypass grafting | U ⁎ | 82 | 9 ⁎ | 9 |

| Asymptomatic, high coronary heart disease risk (Adult Treatment Panel III risk criteria) | A ⁎ | 23 | 11 | 67 ⁎ |

| Risk assessment after revascularization, incomplete revascularization with additional revascularization possible | A ⁎ | 33 | 8 | 59 ⁎ |

| Stress echocardiographic representative vignettes | 23 | 7 | 70 | |

| Asymptomatic with high coronary heart disease risk (Framingham) | U ⁎ | 19 | 9 ⁎ | 72 |

| Evaluation of chest pain syndrome or angina equivalent; high pretest probability of coronary artery disease regardless of electrocardiographic interpretability and ability to exercise | A ⁎ | 26 | 5 | 69 ⁎ |

| Risk assessment after revascularization, symptomatic, not in early postprocedure period | A ⁎ | 27 | 8 | 65 ⁎ |

| Evaluation of chest pain syndrome or angina equivalent; high pretest probability of coronary artery disease regardless of electrocardiographic interpretability and ability to exercise | A ⁎ | 19 | 6 | 74 ⁎ |

| Cardiac computed tomographic angiographic representative vignettes | 57 | 11 | 32 | |

| Asymptomatic patients without known coronary artery disease; low coronary heart disease risk | I ⁎ | 81 ⁎ | 9 | 9 |

| Nonacute symptoms possibly representing an ischemic equivalent, electrocardiogram interpretable, and able to exercise, intermediate probability of coronary artery disease | A ⁎ | 32 | 10 | 58 |

| Asymptomatic, previous coronary artery bypass grafting ≥5 years | U ⁎ | 69 | 16 ⁎ | 15 |

| Symptomatic (ischemic equivalent), evaluation of graft patency after coronary artery bypass grafting | A ⁎ | 47 | 9 | 43 ⁎ |

| Overall | 41 | 9 | 50 | |

In total 1,349 physicians were invited, of whom 129 (9.6%) responded to the survey. Physician replies were anonymous, although they could provide an e-mail address of their choice for the raffle. Characteristics of practices were collected by physician self-report and included academic/private practice, urban/suburban/rural, physician ownership of facilities using MPS, STE, and CCTA, state and country, number of patients seen per week, and income. Physician characteristics included age, years in practice, and level of board certification for MPS, STE, CCTA, and interventional cardiology. At the end of the survey, 1 physician was chosen with a random number generator to receive the iPad.

Three board-certified cardiology physician investigators, each of whom has certification at level II and/or III in echocardiography, nuclear cardiology, and CCTA (J.K.M., F.Y.L., and R.J.K.), independently reviewed the vignettes and chose the applicable AUC indication category for each vignette, with consensus achieved by agreement of ≥2 of 3 on the indication category. Overall kappa between raters was 0.82. Investigators did not rate appropriateness of the indication or the vignette. Subsequently, the appropriateness rating of each chosen indication was applied to the vignette from published AUC statements, regardless of physician investigator agreement with the published appropriateness rating.

Concordance between physicians and AUC rating was measured by assigning scores of 100% for complete agreement, 50% for disagreement by 1 category (e.g., inappropriate vs uncertain, appropriate vs uncertain), and 0% for disagreement by 2 categories (e.g., inappropriate vs appropriate). To compare procedure preference between types of tests of choice normalized for the number of vignettes for each type, we calculated a summary measurement as follows: percent studies by MPS that the physician changed to an alternative procedure that was not MPS was subtracted from percent studies not by MPS that the physician changed to MPS. For example, a physician who changed all studies by MPS to alternative procedures or no testing (100%) but did not modify vignettes not using MPS (0%) would have a procedure preference for MPS of −100%.

The impact of physician and practice characteristics on physician concordance and procedure preference was evaluated using Student’s t test for binary, analysis of variance for categorical, and linear regression for continuous variables. To examine the impact of AUC indication characteristics on physician concordance with AUC ratings, random effects modeling was used to account for correlation among indications within the same physician. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We estimated that 108 physicians would be required to observe a difference between physicians with and without board certification of 10% in concordance with 80% power and alpha 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, http://www.sas.com ).

Results

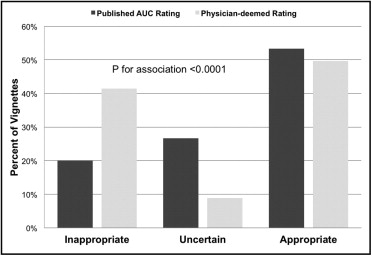

In total 129 cardiologists participated, with board certifications in 65%, 39%, and 32% for MPS, echocardiography, and CCTA, respectively ( Table 2 ). Overall, surveyed cardiologists were concordant with published AUC ratings 65% of the time. Cardiologists’ ratings significantly differed from published AUC ratings for all categories (appropriate, 50% vs 53%; inappropriate, 42% vs 20%; uncertain, 9% vs 27%, p <0.0001 for all comparisons; Figure 1 ) . When categorized as inappropriate and noninappropriate (with appropriate and uncertain combined into a single category), agreement among cardiologists was 64%.

| Physician Characteristics | Mean ± SD (n = 129) | Concordance (n = 129) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All physicians | 65% | N/A | |

| Age (years) | 49.5 ± 9.6 | −0.8% per decade | 0.43 ⁎ |

| Men | 89% | 65% | 0.78 † |

| Years since residency | 17.9 ± 9.7 | 1.1% per decade | 0.32 ⁎ |

| Yearly income | 0.94 ‡ | ||

| 100,000–300,000 | 34% | 63% | |

| 300,000–500,000 | 37% | 64% | |

| >500,000 | 28% | 64% | |

| Board certification | |||

| Interventional | 39% | 65% | 0.77 † |

| Myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomographic board certification | 66% | 66% | 0.81 † |

| Echocardiographic board certification | 39% | 64% | 0.25 † |

| Cardiac computed tomographic angiographic board certification | 65% | 68% | 0.04 † |

| Number of board certifications | .2 ± 1.0 | 0.5% per procedure | 0.60 ⁎ |

⁎ Pearson correlation coefficient.

Cardiologists board certified in CCTA demonstrated higher concordance with published AUC ratings (68% vs 64%, p = 0.04), with no significant differences observed for board certification, academic practice, ownership, or interpretation of procedures using MPS or echocardiography ( Table 3 ). Cardiologist concordance for indications deemed appropriate or inappropriate by AUC was higher than for indications deemed uncertain by AUC (69% vs 69% vs 55% respectively, p <0.0001; Table 4 ). Concordance was lowest for men, >65 years old, and previous revascularization. In patients with no known CAD, concordance was lower for intermediate-risk compared to high- and low-risk patients (56% vs 69% vs 71%, respectively, p = 0.0002). There was no difference in concordance in vignettes using MPS, STE, and CCTA.

| Practice characteristics | Mean ± SD (n = 129) | Concordance (n = 129) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practice type | |||

| Academic | 26% | 63% | 0.28 ⁎ |

| Private practice | 74% | 66% | |

| Number of patients seen per week | 64.3 ± 32.2 | −0.02% per patient | 0.58 † |

| Practice location | 0.25 ‡ | ||

| Urban | 44% | 64% | |

| Suburban | 49% | 66% | |

| Rural | 7% | 69% | |

| Geographic area | 0.21 ‡ | ||

| Midwest | 25% | 64% | |

| Northeast | 29% | 64% | |

| South | 26% | 68% | |

| West | 19% | 67% | |

| Outside United States | 1% | 47% | |

| Ownership of | |||

| Catheterization laboratory | 12% | 69% | 0.42 ⁎ |

| Myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography | 87% | 66% | 0.76 ⁎ |

| Echocardiograph | 92% | 66% | 0.88 ⁎ |

| Cardiac computed tomographic angiography | 31% | 64% | 0.21 ⁎ |

| Number of procedures owned by practice | 2.2 ± 0.8 | −0.7% per procedure | 0.63 † |

| Actively interpreting | |||

| Myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomogram | 77% | 66% | 0.43 ⁎ |

| Echocardiogram | 93% | 66% | 0.52 ⁎ |

| Cardiac computed tomographic angiogram | 60% | 65% | 0.87 ⁎ |

| Number of procedures interpreted by physician | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.8% per procedure | 0.57 † |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree