Predominantly in children

Predominantly in adults

Rhabdomyoma

Myxoma

Fibroma

Papillary fibroelastoma

Purkinje cell tumour

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum. Lipoma

Teratoma

Hemangioma- Angiosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Lymphomas

Myxoma

Paraganglioma

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour

Undifferentiated and synovial sarcomas

Pericardial mesothelioma

Cardiac masses, either tumoural or thrombotic, may cause a variety of clinical presentations. In asymptomatic patients, diagnosis is usually incidental as a result of an imaging test obtained for an unrelated reason. In patients with symptoms, clinical presentation depends on the size of the mass, anatomic location, and friability or ability to embolise. With regards to size and location, these lesions occupy the intracardiac space, and as a consequence the filling of the cardiac chamber where they locate may be compromised. Masses in the left atrium and ventricle may generate clinical signs of pulmonary congestion (dyspnoea, intolerance to supine decubitus), whereas masses in the right heart chambers largely promote signs of venous congestion (oedema or jugular ingurgitation). Malignant tumours that invade the pericardium can provoke episodes of cardiac tamponade.

Independent of their dimensions, if lesions invade the myocardium in depth, clinical presentation will result from different types of arrhythmias: bradycardia due to cardiac blocks, if the lesion alters the integrity of the cardiac conduction system (AV node, His bundle), or atrial or ventricular tachycardias if the lesion damages or irritates the myocardium. In a study by Cina et al. (1996), on a series of 120 cases, the authours reported that AV node tumours, fibromas and atrial myxomas were among the type of tumours in which the first manifestation was mainly sudden death. Finally, depending on the morphological features, the mobility and the disintegration risk, cardiac masses can embolise and provoke symptomatology due to the resultant ischaemia produced in the target organ, which is commonly the brain, although peripheral territories or even coronary arteries can also be involved.

A definite diagnosis can only be completed after histological examination of samples taken at autopsy or biopsy. In clinical practice, biopsies can be obtained by catheterisation in situations where the mass is located in the right chambers, since a possible embolism secondary to the procedure would have less clinical consequences than if the mass was located in the left chambers. Accessibility and mobility also determine whether or not a biopsy is recommended. In those instances where a biopsy is not a safe choice, a surgical intervention should be performed.

Patient prognosis depends on the type of primary tumour, invasiveness in the heart and other organs, and on the possibility of surgical resection. Regarding the latter, imaging techniques such as echocardiography, CT and CMR are of special value. Recent advances in imaging have allowed a better prediction of the different possible diagnoses that, as mentioned previously, can only be certain after histopathological examination.

Echocardiography is the most available imaging technique and the one most commonly used to establish the presence of a myocardial mass. However, it does not accurately differentiate between a thrombus and a benign or malignant tumour. Clinical features help in the diagnosis; for example, atrial fibrillation in the presence of a mass in the atrial appendage, or masses located on a post infarction ventricular aneurysm, are indicative of a thrombus. MRI offers a high spatial resolution and is the best modality for characterising tumour tissue and vascularity. When MRI is not indicated, for example in patients with claustrophobia or carrying a pacemaker or defibrillator, then computed tomography (CT) is an alternative. CT can be used to locate and identify calcifications and to visualise the mass in relation to the coronary arteries. It is generally assumed that the following features suggest malignancy: location in the right chambers, ill-defined borders, wide implantation base, size greater than 5 cm, involvement of several chambers, mediastinum or great vessels, and associated pericardial effusion.

Diagnostic approaches and differential diagnosis of the distinct cardiac masses, based on the characteristics identified in each of the imaging modalities, are summarised in Table 12.2.

Remarks |

Primary cardiac tumours: |

75 % of them are benign |

Their incidence is increasing |

Have been described in all ages, from foetuses to the elderly |

Can manifest with obstruction, embolisation and cardiac arrhythmias |

Can cause or debut as sudden death |

Definite diagnosis is done by histopathology |

Table 12.2

Characteristics of cardiac tumours based on imaging techniques

Mass | Echocardiogram | Magnetic resonance | Tomography |

|---|---|---|---|

Thrombus | Commonly located on ventricular aneurysms, atrial appendage or mechanical prosthesis. Use of contrast agents does not produce an enhancement | Appearance of the lesion may vary in T1–T2, without first-pass or delayed contrast enhancement | Low attenuation with possible attenuation foci |

Myxoma | Heterogeneous appearance. Often pediculated. Main differential diagnosis with thrombus. Most common location is in the left atrium, typically in the atrial septum in the region of the fossa ovalis. Unlike thrombus myxoma appears enhanced after contrast administration | T1-weighted sequences show isointense or hypointense signals in relation to the myocardium, whereas lesions are hyperenhanced in T2. Contrast enhancement. Occasional heterogeneous appearance may be due to necrotising and haemorrhagic areas | 14 % show calcifications |

Fibroelastoma | Small and mobile. Generally located in valves or in subvalvular apparatus. Signal intensity is equal to or denser than the myocardium | Difficult to characterise given the small size and mobility. Well-circumscribed. Intermediate signal, similar to endocardium, in T1 and T2. Homogeneous delayed enhancement due to fibroelastic tissue | Low attenuation focal lesion |

Lipoma | Homogeneous appearance. Frequently located in septum or intramyocardial | Well-circumscribed. Can be diagnosed due to fatty suppression in the T1 and T2 sequences. Bright T1 sequence with the “black blood” technique. Low intensity signal on T2 | Circumscribed lesion with fatty attenuation |

Haemangioma | Very variable appearance and location, intramural or cavitaries | Isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense T2 sequences relative to the myocardium. Signal intensity intermediate between blood and myocardium, in the “white blood technique”. Heterogeneous, but intense and prolonged delayed enhancement | Calcification foci and significant contrast enhancement |

In general, heterogeneous and hyperechogenic lesions. Cavern images, sometimes multiloculated, with trabeculae and free spaces. It can also appear as globally hypodense | |||

Fibroma | Usually intramyocardial and causes a thickening which is hard to distinguish from LV hypertrophy. Hyperechogenic with no contractility. Alterations in strain rate parameters | Well circumscribed and of low intensity. Ring that surrounds and compresses the myocardium. Isointense on T1- and hypointense on T2- weighted images, relative to the myocardium. Absence of gadolinium contrast enhancement due to low vascularisation, although sometimes lesions offer delayed homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement | Calcification foci are present in 50 % of the cases |

Rhabdomyoma | Young patients, often associated with tuberous sclerosis in up to 50 % of cases. Intramyocardial location, often in the septum. They are typically multiple, between 0.1 and 9 cm in size, hyperechoic and not calcified | Iso- to hyperintense signals on T1 weighted images and hyperintense on T2 sequences (in contrast to fibroma). Uniform and intense delayed enhancement | |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | Arises from the myocardium towards any of the chambers. Often affects or invades the valvular apparatus | Heterogeneous signals on T1 and T2- weighted images. Solid peripheral component hyperintense with contrast enhancement | Low attenuation signal |

Angiosarcoma | 75 % of these are found in the right atrium and involve the pericardium, tricuspid valve and right ventricle. Blood flow inside the lesion. Pericardial effusion is common | Isointense and hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, respectively. Marked enhancement, blood flow within the neoplasm | Mass of heterogeneous enhancement. Highly attenuated pericardial effusion |

Sarcoma with osteo-, myo or fibroblastic differentiation | Predominantly in the left atrial wall that can spread and invade adjacent areas. Young adults | Heterogeneous, infiltrating | Osteosarcoma shows calcification |

Lymphoma | Preferentially in the right chambers. Cardial wall thickening. Ventricular dysfunction. Pericardial effusion | Hypointense as seen on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2 sequences. Heterogeneous contrast enhancement | Hypodense or isodense relative to the myocardium. Heterogeneous contrast enhancement. Mediastinum involvement |

12.2 Cardiac Myxomas

Myxomas are tumours of uncertain histogenesis that appear exclusively in the heart. Cardiac myxomas represent the most common primary cardiac tumour, especially in persons between the ages of 30 and 60 years (mean age at presentation is 50 years), with two thirds of the cases involving women. Around 80–90 % of myxomas are located in the left atrium, arising from the fossa ovalis, and around 15 % appear in the right atrium. The majority of myxomas are pedunculated and have a stalk that inserts into the region of the fossa ovalis (Fig. 12.1a); this can elongate, and allow the protrusion of the mass through the valvular orifice. Myxomas are heterogeneous in size, and in general range from 1.5 to 7 cm, although in some cases they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. In 90 % of the cases, there is a single tumour. The morphological characteristics of cardiac myxomas are summarised in Table 12.3.

Fig. 12.1

Myxoma in the left atrium. A 43-year-old woman with a history of anxiety and depression was feeling unwell and died while being taken to hospital. Heart weight was 314 g. Coronary arteries were permeable. (a) A tumour of 1.7 cm, polyploid, with a jelly-like consistency, irregular surface, and friable, was present in the left atrium at the level of the fossa ovalis. (b) Section shows the tumour implanted on the endocardium, without infiltrating the atrial wall. (c) Several whitish and softened areas can be observed in the myocardium; the largest area in the posterior zone of the ventricular septum. (d) Microscopically, the tumour consists of a proliferation of cells that are arranged forming cords embedded in an abundant myxomatous stroma, where isolated stellate cells can be observed. (e) In samples taken from the softened areas of the myocardium, infarcted areas and the presence of several intramural arteries that contain emboli from the myxoma can be observed. Infarcts show different degrees of evolution, with some areas at the level of the septum with recent myocyte necrosis, suggestive of repeated embolisation episodes

Table 12.3

Pathology of cardiac myxomas

Macroscopic features: |

35 % of them have a papillary, gelatinous and friable surface (tends to embolise) (Fig. 12.1a) |

65 % of them are solid, with a smooth surface (clinically they cause heart failure) (Fig. 12.2a) |

Usually present haemorrhagic areas that confer a heterogeneous colour, and are surrounded by fibrin (Fig. 12.2b) |

The tumour may become calcified, more common in myxomas located in the right atrium (Fig. 12.2b) |

Microscopic features: |

Tumoral cells are stellate, round or fusiform, dispersed on loose stroma rich in acid mucopolysaccharides |

Myxoma cells may be arranged in cords or around the vessels |

The stroma contains infiltrates of lymphocytes or plasma cells, haemorrhagic areas with siderophages, collagenised zones and ossification (Fig. 12.3b) |

The surface is delineated by grooves of endothelial cells and fibrin deposits, which can embolise with the tumour |

The majority of myxomas are diagnosed through H&E staining |

Immunohistochemistry: myxoma cells are positive for calretinin (Fig. 12.4) and endothelial markers e.g. CD34 and CD31 |

Clinical presentation is very variable. They can manifest with congestive symptoms due to the obstruction of blood resulting from the presence of a mass within the cardiac chambers. Left atrial myxomas cause pulmonary congestion whereas right atrial myxomas provoke generalised oedemas. In more than one third of myxomas, symptomatology results from embolisation occurring in any systemic tissue, or in the pulmonary territories, dependent upon tumour location. This is especially frequent in myxomas with a papillary and friable surface.

Approximately 20 % of patients present a constitutional syndrome secondary to IL-6 production by tumour cells, with fever, arthralgia, weight loss, anorexia and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Myxomas smaller than 4 cm are usually asymptomatic and may be discovered incidentally. Myxomas can debut as sudden death. In children, there are reports of sudden death due to myxomas located in the right atrium or tricuspid valve, as a consequence of pulmonary thromboembolism. Although infection of a myxoma is rare, when present, the initial manifestations mimic those of infective endocarditis or vasculitis.

Fig. 12.2

Myxoma in the right atrium. An 84-year-old woman examined at the Cardiology Department due to dyspnoea. She was diagnosed with a tumour in the right atrium. She died suddenly at home. Heart weight was 422 g, with permeable coronary arteries. (a, b) The right atrial chamber was occupied by a firm nodule, round in shape, of a maximum diameter of 5.3 cm, with a greyish and smooth external surface with yellowish or brown areas. (c) Histology revealed extensive fibrosis and haemorrhagia, and areas myxomatous in appearance, with the tumour cells arranged around the vessels, and abundant siderophages in the stroma

Fig. 12.3

Myxoma in the left atrium. A 68-year-old woman who died suddenly at home. Heart weighted 434 g and coronary arteries were permeable. (a) The sole autopsy finding was a tumoural node, round in shape, 3 cm in diameter, with a part of its surface smooth and the other lobulated. The tumour had a stalk of 1 cm in length arising from the fossa ovalis. Sectioning showed a firm tumour, with calcified areas and zones ochre in colour. (b) Histology showed extensive fibrosis, abundant siderophages and a focus of bone metaplasia around myxoma debris, with the typical perivascular arrangement

Fig. 12.4

Myxoma. Strong positivity for calretinin (Courtesy of Sara Chaves. FJD-Capio)

Around 5 % of all cardiac myxomas are associated with Carney complex, which should be suspected in patients with spotty skin pigmentation, atypical location, or multiple or recurrent myxomas. Familial myxomas affect younger people compared with sporadic myxomas, and usually recur in 10 % of the cases. Carney complex is most commonly caused by mutations in the PRKAR1A gene, which is a tumour suppressor. In these cases, a familial study is recommended.

Echocardiography, which is the method of choice for diagnosis, reveals the presence of pediculated and mobile masses. Differential diagnosis with atrial thrombus, fibroelastoma or atrial septal aneurysm (described below) should be carried out. However, a definitive diagnosis cannot be established until pathological examination is completed. This is performed by biopsy or after tumour resection, indicated if diagnosis of thrombus is inconclusive.

12.3 Tumours of Cardiac Muscle

Rhabdomyomas and rhabdomyosarcomas occur in the paediatric age group. There is also an extremely rare type of tumour that is formed by mature myocytes, termed hamartoma.

12.3.1 Rhabdomyomas

Cardiac rhabdomyomas represent the most common cardiac tumour in paediatric patients. As occurs with other tumours of the heart, clinical presentation depends on the location, size and number. Tumours may manifest as arrhythmias, blood flow obstruction, heart failure, pericardial effusion and sudden death. Echocardiography is the most effective imaging technique to provide adequate information for diagnosis of rhabdomyomas. Furthermore, given that these types of tumours constitute an important cause of foetal hydrops and intrauterine deaths, echocardiography is also especially important during the gestational period. Tumours appear as intramural or intracavitary masses, well circumscribed and echogenic, which can occur in any location in the heart but are more common in the ventricles.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas can be divided in three groups: sporadic, those that appear in tuberous sclerosis, and those associated with cardiac malformations such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of great vessels, etc. Most children with rhabdomyoma have tuberous sclerosis. Two altered genes have been confirmed for tuberous sclerosis: TSC–1 on chromosome 9q34 that encodes hamartin, and TSC–2 on chromosome 16p13 that encodes tuberin. Both genes are tumour suppressors.

Rhabdomyomas have a natural history of spontaneous regression and hence, regular monitoring by echography is sufficient. Surgical resection is limited to cases of blood flow obstruction, or arrhythmias that do not respond to pharmacological treatment. Morphology is summarised in Table 12.4.

Table 12.4

Pathology of cardiac rhabdomyomas

Macroscopic features: |

They most often occur in the ventricles (Fig. 12.5a) |

Well-demarcated nodules, generally single, that can become quite large, especially in sporadic cases |

Whitish and firm nodules, in contrast to the surrounding myocardium |

In patients with tuberous sclerosis, nodules are multiple and can be numerous |

Microscopic features: |

They are formed by enlarged cells with a monomorphic central nucleus and a clear and vacuolated cytoplasm (Fig. 12.5c) |

Some cells adopt a morphology that resembles a spider (“spider cells”), due to a radial distribution of the myofilaments around the nucleus |

Cytoplasm is PAS (+) due to abundant intracellular glycogen content |

Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate cells positive for myoglobin, desmin, actin and vimentin |

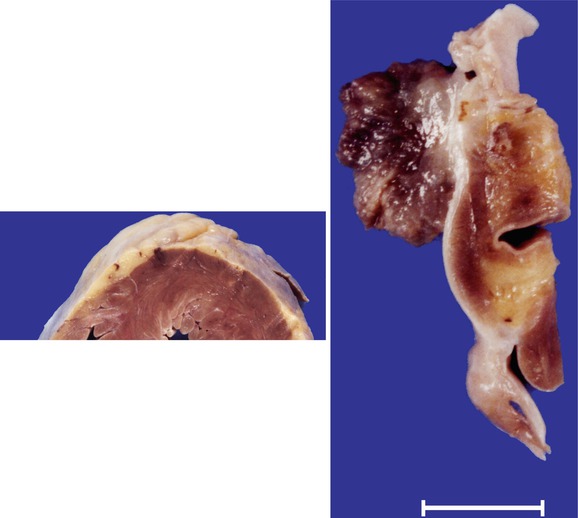

Fig. 12.5

Rhabdomyoma. A 15-year-old girl, with a slight developmental delay. She did not show any symptomatology before suffering syncope and cardiac arrest. Heart weight, 310 g. (a) Cross-section of the ventricles showed well-circumscribed pale areas mainly in the ventricular septum. (b) Microscopic low-power view showing pale appearance of the tumour in contrast to the surrounding myocardium (Masson´s trichrome). (c) High magnification of the tumour shows cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, in contrast to the normal myocardium that appears at the top of the picture

12.3.2 Rhabdomyosarcomas

Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignant tumours with a morphology that resembles skeletal muscle. Primary cardiac rhabdomyosarcomas are very rare and are observed primarily in children and young adults, although some cases have also been reported in the elderly. They occur in the atria or the ventricles, but can also arise from the mitral valve (Fig. 12.6a). Due to their large dimensions, they can provoke an obstruction in the blood flow of the heart.

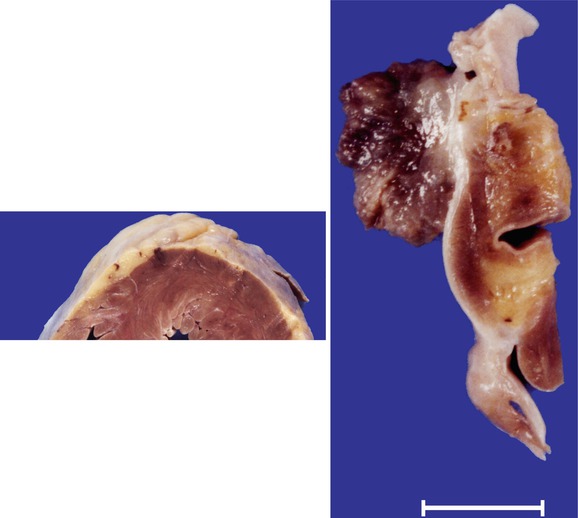

Fig. 12.6

Rhabdomyosarcoma. A 36-year-old patient. (a) Autopsy reveals an exophytic mass in the posterior wall of the left atrium. (b) Photomicrography showing a lesion formed by pleomorphic cells, some of them with the typical tadpole shape and cytoplasm striations (Courtesy of Dr. Gaetano Thiene and Dr. Cristina Basso. Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Sciences. Padua University. Italy)

Histologically, cardiac rhabdomyosarcomas are embryonal, and rhabdomyoblasts can be identified by the presence of cytoplasm cross striations or a typical tadpole shape (Fig. 12.6b). These cells are positive for desmin.

12.4 Fibromas

Cardiac fibromas are mesenchymal tumours composed of fibroblasts and collagen. They are discovered in children, often before 1 year of age, teenagers and young adults. There is no sex predominance. Although tumours are well circumscribed macroscopically, histological examination shows undefined borders due to infiltration in the surrounding myocardium. Symptomatology is caused by obstruction in blood flow or interference with valvular function, and can manifest as arrhythmias, syncope, or even sudden death. Total or partial resection is indicated when the tumour grows uncontrollably and/or if the patient is clinically compromised, usually with congestive signs. Heart transplantation is an option when the tumour proves unresectable. Morphology is summarised in Table 12.5.

Table 12.5

Pathology of cardiac fibromas

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree