Described herein are clinical and necropsy findings in a 61-year-old woman with fatal left ventricular diastolic failure secondary to massive calcific deposits primarily within the left ventricular cavity. At age 3, an isthmic aortic coarctation was resected, and at age 44, a stenotic congenitally bicuspid aortic valve was replaced. The cause of the intracavitary calcific deposits remains unclear, but surgical resection of the deposits has been an effective form of therapy.

Calcific deposits are common in the heart particularly in older individuals and especially in atherosclerotic plaques in coronary arteries, in aortic valve cusps, and in the mitral annulus. These deposits may also occur but far less commonly in other areas of the heart. In 1984, Silver et al described clinical and necropsy findings in a 56-year-old woman with numerous calcific deposits in the left ventricular cavity causing severe impairment to left ventricular filling. This report describes clinical and necropsy findings in a similar patient and reviews other reported cases of large, mainly intracavitary, left ventricular calcific deposits.

Case Report

This 61-year-old white woman had resection of an aortic isthmic coarctation at age 3. At age 44, she underwent an aortic valve replacement with a bileaflet mechanical prosthesis for a stenotic congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. At age 54 (2006), she experienced her first episode of acute pulmonary edema requiring mechanical ventilator. Coronary angiography showed significant narrowing of the left circumflex coronary artery and a stent was inserted. A year later (age 55), another acute episode of heart failure occurred. Repeat angiography disclosed that the lumen of the stent in the left circumflex coronary artery was partially thrombosed, the clot was extracted, and angioplasty was performed. Echocardiogram disclosed a left ventricular ejection fraction of about 30%, but the prosthesis in the aortic valve position was functioning well. She had another episode of acute pulmonary edema 1 year later.

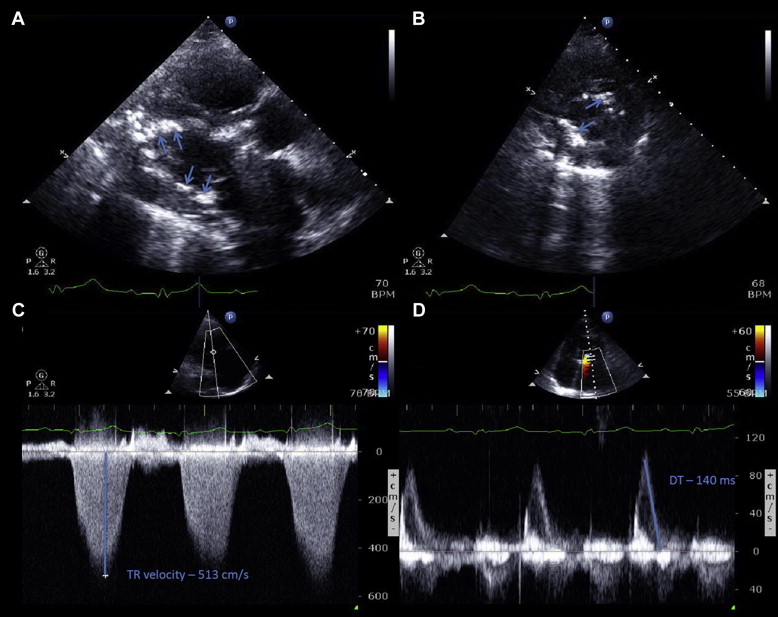

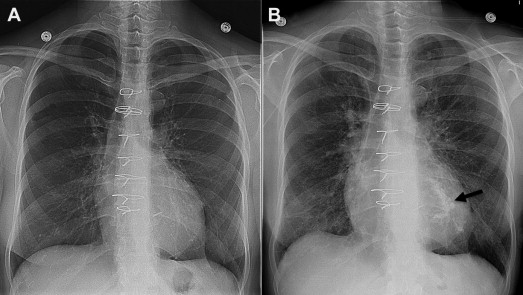

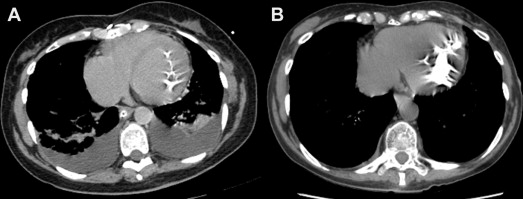

Because of increasing fatigue and periodic evidence of worsening heart failure, she was admitted to the Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, for the first time at age 59 (February 2011). An echocardiogram, at that time, disclosed severe left ventricular endocardial thickening with numerous intracavitary calcific deposits, a restrictive left ventricular filling pattern without respiratory variation, normal-sized right and left ventricular cavities, and a normally functioning aortic valve prosthesis. The cavitary calcific deposits were also seen by chest radiographs and by chest computed tomography. Right-sided cardiac catheterization showed the following pressures in mm Hg: pulmonary arterial wedge mean 20, a wave 26, v-wave 40, pulmonary artery 72/24, and right ventricle 78/15. The cardiac index was 2.25 L/min/m 2 .

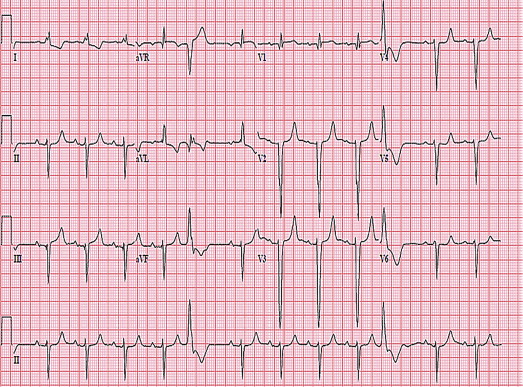

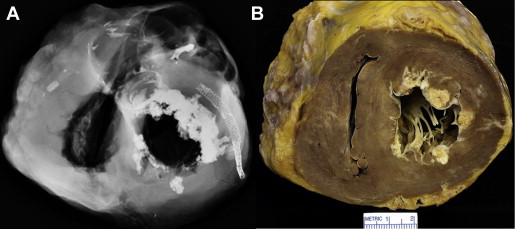

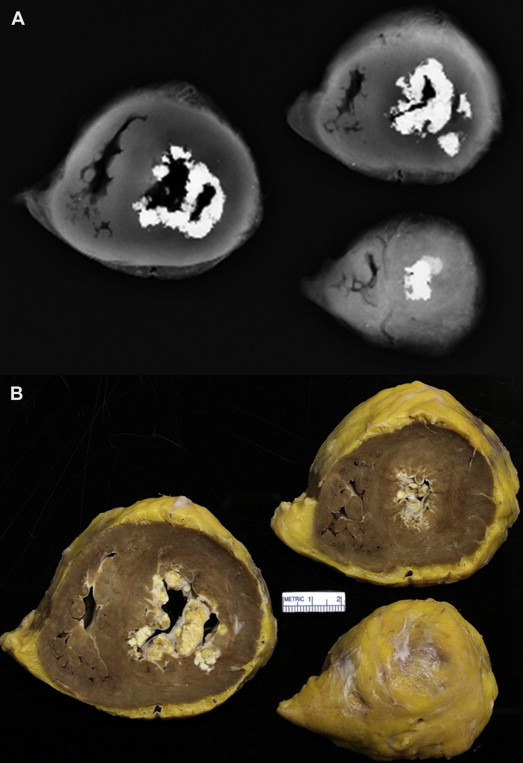

Over the next 2 years, the heart failure gradually worsened. Her body mass index was 17 kg/m 2 . The pulmonary arterial pressure rose to 99/29, the right ventricular pressure to 99/0, and the pulmonary arterial wedge pressure to mean 30, a wave 38, and v wave 33 mm Hg. Echocardiogram ( Figure 1 ) revealed findings similar to the one performed 2 years earlier. Repeat chest radiograph showed more left ventricular intracavitary calcific deposits ( Figure 2 ) than had been seen 5 years earlier. Computed tomography ( Figure 3 ) showed the calcific deposits filling the left ventricular cavity. An electrocardiogram a month before death is shown in Figure 4 . Cardiopulmonary transplantation was deemed inappropriate and she died of heart failure in August 2013 at age 61.

Numerous serum calcium levels were available between June 2007 and August 2013 and ranged from 8.1 to 9.5 mg/dl. Several serum phosphorous levels in February 2008 ranged from 2.4 to 3.6 mg/dl.

At necropsy, the heart weighed 440 g. Huge calcific deposits were present in the left ventricular cavity from apex to base ( Figures 5 and 6 ). The right ventricular and left ventricular walls and the ventricular septum were of similar thicknesses and free of grossly visible myocardial lesions, and neither ventricular cavity was dilated. Histologically, sections of the myocardium were normal except for enlargement of the myofibers. The discs of the mechanical prosthesis (St. Jude Medical) in the aortic valve position appeared to move properly without interference. Metallic stents were present in the left circumflex coronary artery ( Figure 3 ). The right and left anterior descending coronary arteries were virtually free of atherosclerotic plaques. The right atrium was larger than the left atrium. A saccular aneurysm with a very thin wall was present at the aortic anastomotic site where the isthmic aortic coarctation had been resected.

The right pleural space contained 750 ml and the left 950 ml of serous fluid. Sections of the lungs stained by the Movat method showed that the media of the pulmonary arteries were thickened, and many had mild thickening of the intima, but no plexiform lesions were present. The intrapulmonary pulmonary veins were dilated, the interlobular septa were thickened (Kerley B lines), and extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present in some alveolar spaces. Although most were of normal thickness, some alveolar septa were thickened by fibrous tissue.

Discussion

The patient described herein is virtually identical to the one described in 1984 by Silver et al with huge intracavitary left ventricular calcific deposits leading to extreme difficulty in filling the left ventricular cavity with resulting severe secondary pulmonary hypertension.

In recent years, a number of reports have appeared describing calcific deposits in 1 or more cardiac chambers. Reynolds et al in 1997 coined the phrase “calcified amorphous tumor of the heart” to characterize the cardiac calcific deposits because the individual calcific deposits are held together by an “amorphous material,” mainly fibrous tissue. In our patient, the intracavitary calcific deposits were essentially “glued” together and to the mural endocardium by the “amorphous” material that prevented the left ventricular cavity from expanding much during ventricular diastole. Similar huge calcific deposits within the left ventricular and ventricular septal walls unassociated with similar intracavitary calcific deposits can result in similar restriction of left ventricular diastolic filling. A list of reported cases of left ventricular wall and/or intracavitary huge calcific deposits is listed in Table 1 . The calcific deposits in each of these patients were clearly visible by echocardiographic and/or computed tomographic studies. Cases in which the calcific deposits involved cardiac valves were excluded from the list.