Cardiac Neoplasms

Primary cardiac tumors are rare occurring with a prevalence ranging from 0.001% to 0.03% in unselected autopsy series. Metastatic involvement of the heart is significantly more common, present at autopsy in roughly 20% of patients dying from extracardiac malignancies. The vast majority of primary cardiac tumors are of mesenchymal origin and accordingly display a variety of histopathologies. Over 75% of primary tumors are benign. Symptoms when present may be related to obstruction, interference with valvular structures resulting in regurgitation, direct invasion of the myocardium with associated impaired contractility, arrhythmia and conduction disorders, pericardial effusion, or embolization.1,2

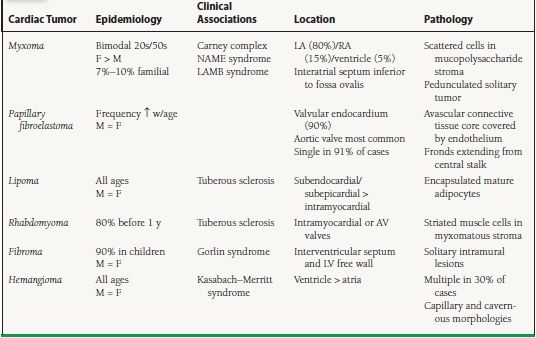

BENIGN TUMORS (TABLE 59.1)

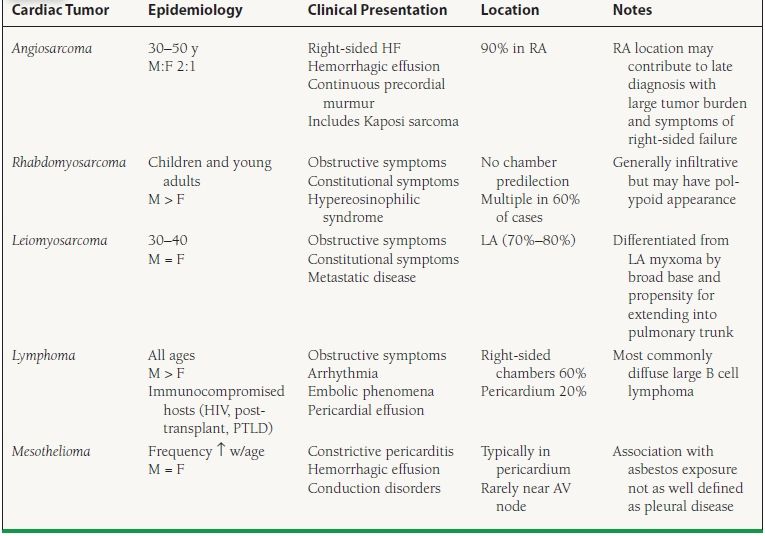

TABLE

59.1 Benign Primary Cardiac Tumors

Myxomas

Myxomas represent the most common primary cardiac tumors in adults, accounting for approximately 25% of all cardiac neoplasms and 75% of all benign primary cardiac tumors. While once thought to represent organized thrombus, gene expression and immunohistochemical studies have firmly concluded that they are neoplasms arising from multipotent mesenchymal cells.3 Myxomas have a bimodal peak onset in the third and sixth decades of life with 65% occurring in women. Seven to ten percent of myxomas are familial in origin.4 The autosomal dominant Carney complex represents the majority of these familial cases and is characterized by cardiac and extracardiac myxomas (breast and skin), lentigines, hyperendocrine states, and nonmyxomatous extracardiac tumors including testicular Sertoli cell tumors, schwannomas, pituitary adenomas, and thyroid tumors. Other familial syndromes associated with myxoma formation include the LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxoma, and blue nevi) and NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibromata, and ephelides) syndromes. In contrast to sporadic cases, familial myxomas have no clear predilection for sex or age, are multicentric, apically located, and more likely to recur following resection (20% of cases in the Carney complex).5

Over 90% of myxomas are solitary with 80% located in the left atrium, most commonly attaching to the interatrial septum at the inferior border of the fossa ovalis. They may however arise from any endocardial surface within the heart with 15% occurring in the right atrium and the remaining 5% arising from the ventricles or atrioventricular (AV) valves.6 Myxomas are pedunculated with surfaces that may be smooth or villous. On gross examination they have a gelatinous consistency with foci of hemorrhage, calcification, ossification, and frequently cystic components. Size at the time of diagnosis is typically 4 to 8 cm in diameter though myxomas as large as 16 cm have been described in the literature.

As with all cardiac tumors, symptoms are highly variable and depend largely on tumor size, location, and mobility. The classic triad of symptoms includes obstructive symptoms (syncope, sudden cardiac death, or symptomatic heart failure [HF]), embolic phenomenon, and constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss, arthralgias, and Raynaud syndrome) thought secondary to release of IL-6. Findings on auscultation include diastolic and systolic murmurs. The characteristic low-pitched “tumor plop ” occurring 80 to 120 ms after S2 (i.e., after an opening snap and prior to a third heart sound) and correlating with tumor movement through the mitral valve and contact with the ventricular wall is heard in only a minority of cases.4

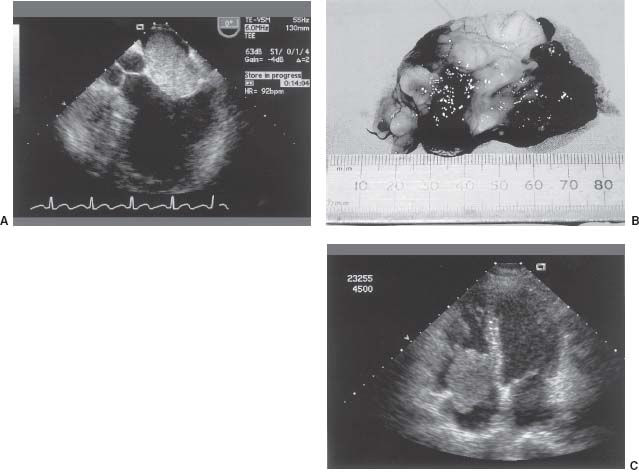

Laboratory abnormalities include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates and C-reactive protein, anemia (often hemolytic), polycythemia, and thrombocytopenia. The diagnosis is made by echocardiography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), or cine gradient-echo cardiac MR (CMR) where myxomas appear as heterogeneous density spherical or ovoid masses (Fig. 59.1). Thrombus is the primary differential diagnosis with protrusion through the mitral annulus being the most specific finding favoring the diagnosis of myxoma.

FIGURE 59.1 A: Left atrial myxoma. B: Surgical specimen, left atrial myxoma (same as part A). C: Right atrial myxoma.

Treatment consists of surgical resection, which is associated with a low operative mortality, and, with the exception of familial cases, a low recurrence rate (0% to 3%). Complete resection of the tumor and avoidance of excessive manipulation is essential to preventing local and distant recurrences, respectively. As with all cardiac tumors, this is best achieved with extracorporeal circulatory support via femoral or azygous vein cannulation in order to avoid tumor fragment embolization, facilitate direct visualization, and rule out metasynchronous tumors. As with all resected cardiac tumors, annual noninvasive imaging is recommended for follow-up.6

Papillary Fibroelastoma

Papillary fibroelastoma is the second most common benign primary cardiac tumor and the most common to involve the cardiac valves. Eighty percent of fibroelastomas occur in the left cardiac chambers with the aortic and mitral valves being the most common sites. Fibroelastomas are typically found on the downstream aspect of the valve and appear as frondlike projections of collagen and elastic fibers emanating from a short central stalk (often described as sea anemone like) (Fig. 59.2). Their small size and highly mobile nature make them best suited to visualization with echocardiography. They can be differentiated from Lambl excrescences by their location on noncontact surfaces of the valve. Symptoms when present are due to systemic embolization with stroke and myocardial infarction being the most feared complications. The current therapeutic approach is surgical excision for fibroelastomas that are highly mobile, > 1 cm in size or associated with prior embolization. In nonsurgical candidates with prior embolic events long-term anticoagulation may be considered.7

Other Benign Primary Cardiac Tumors

Lipoma

Cardiac lipomas are the third most common benign primary cardiac tumors and as their name implies represent well-encapsulated collections of mature adipocytes. Subepicardial and subendocardial locations predominate though intramyocardial locations can also occur. Clinical presentations are largely dictated by location with subepicardial lipomas rarely resulting in symptoms unless very large and associated with pericardial effusion or chamber compression. Subendocardial lesions may result in hemodynamic obstruction when large and intramyocardial lipomas may occasionally present with conduction disorders or arrhythmia. Because lipomas have a nonspecific echocardiographic appearance, CT has become a favored diagnostic modality demonstrating a well-circumscribed mass with low attenuation similar to subcutaneous fat. Surgical resection is reserved for symptomatic cases.8

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum (LHAS) is a nonneoplastic excessive accumulation of nonencapsulated fat > 2 cm in diameter in the superior and inferior portions of the atrial septum, sparing the fossa ovalis. LHAS is more common in elderly, obese, and male patients. Rhythm disturbances and hemodynamic obstruction necessitating surgical intervention are rare.

Rhabdomyoma

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are quite rare in adult populations but represent the most common benign primary cardiac tumors in the pediatric population with more than 80% occurring in patients < 1 year of age. They are thought to represent hamartomatous growths as opposed to true neoplasms with an absence of mitotic activity and a tendency to spontaneously regress. The later characteristic has led to the recommendation that asymptomatic lesions be followed conservatively.4 There is a clear association with tuberous sclerosis with 80% of rhabdomyoma patients having the disease. In these cases multiple tumors are the rule.9

Fibroma

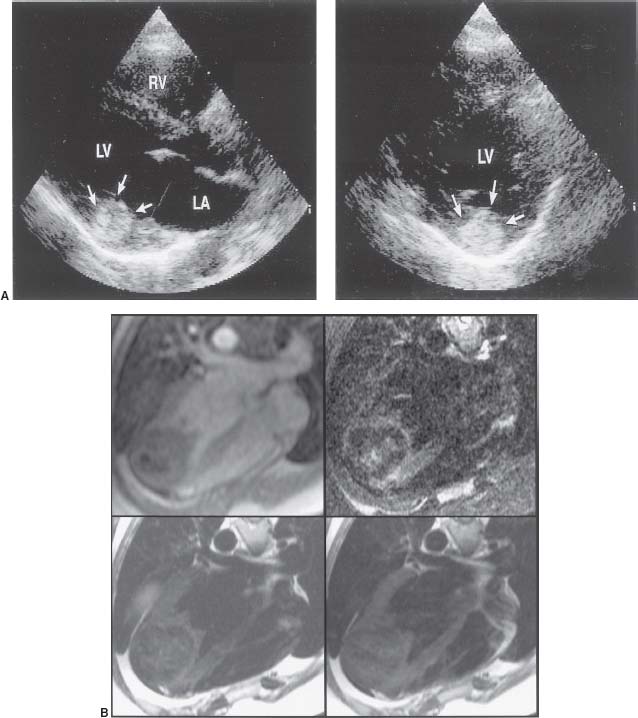

Cardiac fibromas are the second most common benign primary cardiac tumor in pediatric populations and again are rarely seen in adults. They are typically located in the left ventricular (LV) free wall, ventricular septum, or apex with the LV involved five to ten times more frequently than the RV. They can grow to large sizes with clinical presentations including signs and symptoms of mechanical obstruction, congestive HF due to systolic or diastolic dysfunction, or malignant arrhythmias. While nonspecific, the diagnosis is often suggested by the presence of calcification (Fig. 59.3). Definitive treatment involves resection as unlike rhabdomyomas they rarely regress. Cardiac fibromas may occur as part of the Gorlin syndrome (cardiac fibromas, multiple basal cell carcinomas, jaw cysts, and skeletal abnormalities).4

Hemangioma

Cardiac hemangiomas are vascular malformations composed of endothelial-lined channels with interspersed fat and fibrous septa. They represent < 2% of benign primary cardiac tumors and can occur at any age, in any chamber, and at any level from pericardium to endocardium. They appear hyperechoic by echocardiography and have characteristic intense contrast enhancement on CT. Similarly coronary angiography may demonstrate findings consistent with perfusion although in both cases contrast enhancement may vary with “low flow ” cavernous hemangiomas having relatively reduced perfusion. Given that they often regress spontaneously, conservative management is favored in asymptomatic patients.

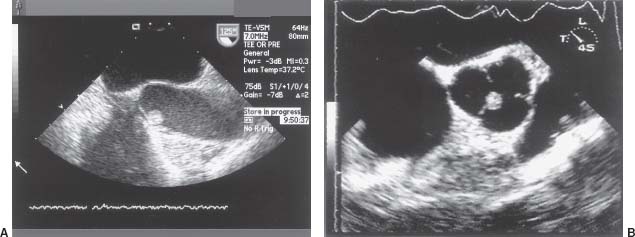

MALIGNANT TUMORS (TABLE 59.2)

TABLE

59.2 Malignant Primary Cardiac Tumors