(“nonsecretors”). Furthermore, up to 25% of patients with ATTR-type amyloidosis have monoclonal immunoglobulins in their serum or urine.4,5 Because treatment is driven by the amyloid protein present, it is necessary to type amyloid when it is identified in cardiac biopsy samples.

TABLE 148.1 Cardiac Amyloidosis, Clinical Findings by Protein Precursor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

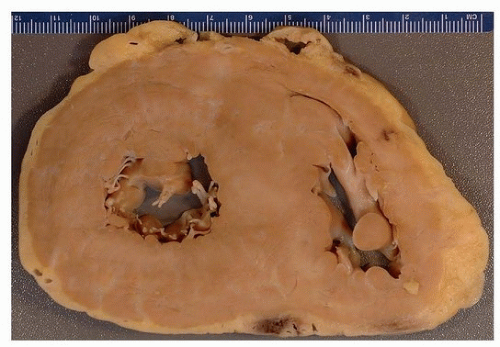

homogenous material (Fig. 148.4) that may exhibit a cracked appearance. In some examples, there may be only interstitial amyloid that may be focal, necessitating careful review of all biopsies (Fig. 148.5). There may be associated myofiber disarray, interstitial fibrosis, and/or hypertrophy (Fig. 148.6). Occasionally, as in other organs, a foreign body-type giant cell reaction is present (Fig. 148.7). The differential diagnosis is fibrosis, which is generally not as randomly distributed, and shows a more fibrillar appearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree