Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy

Joseph J. Maleszewski, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Overview

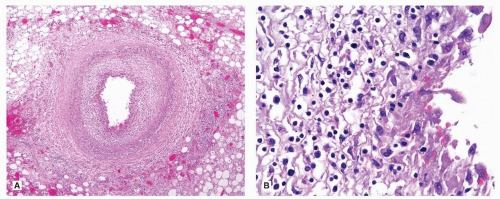

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV, or, loosely, chronic rejection) is a primarily intimal disease that is unique to allograft hearts.1 It remains the main limitation of long-term success in heart transplantation.2,3

CAV involves the indirect allorecognition pathway of cell-mediated response, when antigens from the donor are processed by host dendritic cells and presented as peptides, which in turn trigger lymphocyte activation and vessel injury.4,5 CAV predominantly affects arteries, but occasionally veins can exhibit similar changes.

Incidence and Risk Factors

Any degree of CAV is detectable in 7% of recipients within the first year, in 31.5% of recipients within 5 years, and in 52.7% of survivors within 10 years of transplant.6 The cumulative incidence of obstructive CAV was 7% at 5 years and 23% by 10 years with an 11% cumulative probability of requiring a percutaneous intervention.7

Risk factors for the development of CAV include traditional ones (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome) and those related to transplant and immunosuppression (cytomegalovirus infection, HLA mismatches, and rejection diagnosed by biopsy). A history of cellular or antibody-mediated rejection increases the risk of the development of CAV to 36% at 5 years.6,8

Clinical Diagnosis

CAV presents clinically as congestive heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, or sudden death. Because CAV is concentric and diffuse, angiography, which is best in locating eccentric and focal lesions, is not the modality of choice. Furthermore, CAV frequently affects intramyocardial branches of the epicardial arteries that cannot be detected by imaging.

Modalities that have been used to measure CAV severity and intimal proliferation are dipyridamole myocardial perfusion scanning, dobutamine stress echocardiography, positron emission tomography (PET), cardiac magnetic imaging, computed tomography, and intravascular ultrasound, which is the diagnostic tool of choice.

Endomyocardial biopsy is of little use in the diagnosis of CAV, as chronic ischemic changes, while relatively specific, are insensitive diagnostic markers for the disease.9

Histopathology

In a series of 27 transplant autopsies with a mean of 3 years after surgery, 6 patients had CAV, compared to 13 with typical atherosclerosis and 8 without epicardial coronary disease, indicating that only a minority of transplant autopsies show features of CAV.10 A series of hearts explanted for retransplantation showed that severe (>75%) cross-sectional area luminal narrowing was found in about 25% of hearts and involved the left anterior descending, circumflex, and right coronary arteries about equally.11 Atheromas were described as frequent, even in pediatric hearts, suggesting that not all lipid-rich lesions are from the donor.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree