|

ventricles outside the AV junction, as in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Arrhythmia and features | Causes | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

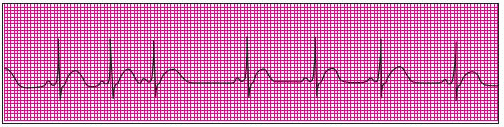

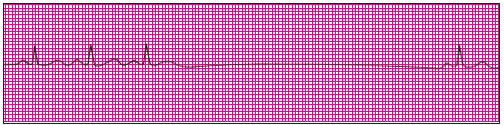

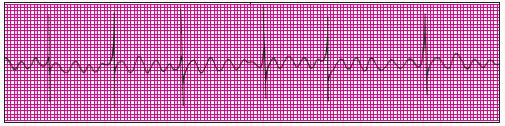

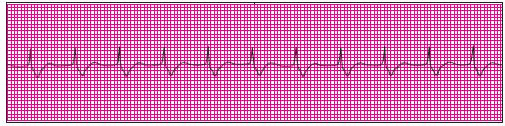

Sinus arrhythmia |

| |

▪ Irregular atrial and ventricular rhythms ▪ Normal P wave preceding each QRS complex | ▪ In athletes, children, and the elderly, a normal variation of normal sinus rhythm ▪ Also seen in digoxin (Lanoxin) toxicity and inferior myocardial infarction (MI) | ▪ Atropine if rate decreases below 40 beats/minute and if patient is symptomatic (hypotension, for example) |

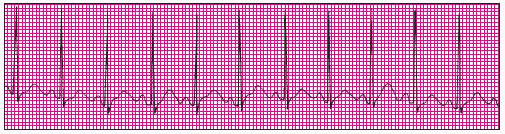

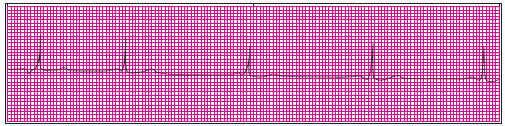

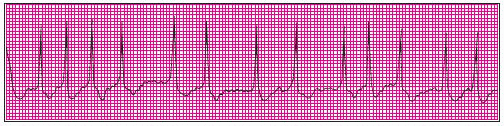

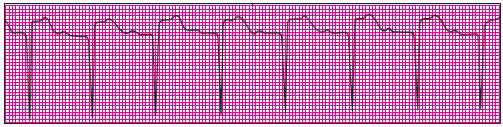

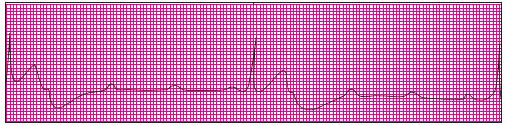

Sinus tachycardia |

| |

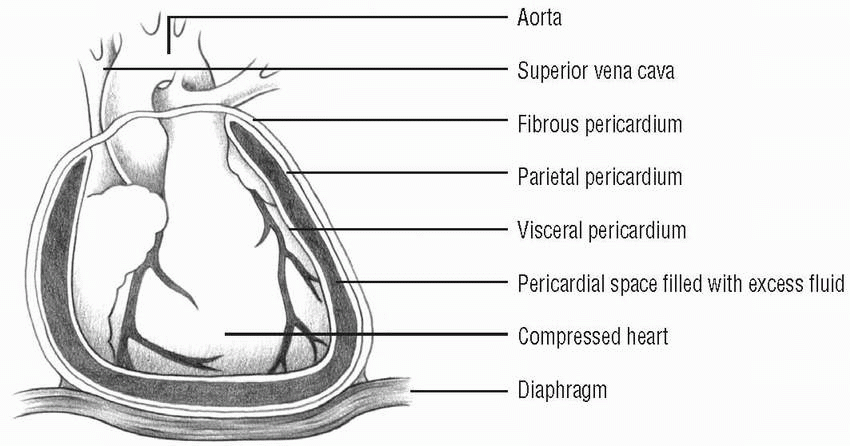

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms regular ▪ Rate greater than 100 beats/minute; rarely, greater than 160 beats/minute ▪ Normal P wave preceding each QRS complex | ▪ Normal physiologic response to fever, exercise, anxiety, pain, dehydration; also may accompany shock, left-sided heart failure, cardiac tamponade, hyperthyroidism, anemia, hypovolemia, pulmonary embolism, anterior MI ▪ Also may occur with atropine, epinephrine, isoproterenol (Isuprel), quinidine, caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine use | ▪ Correction of underlying cause ▪ Beta-adrenergic blockers or calcium channel blockers for symptomatic patients |

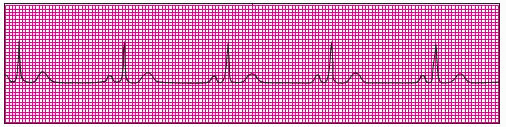

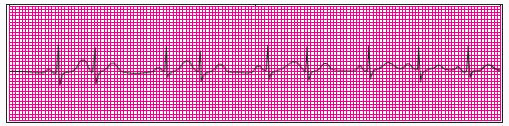

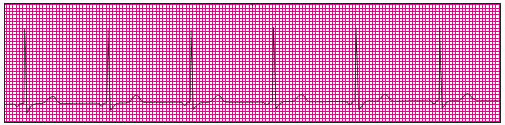

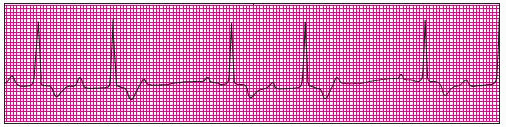

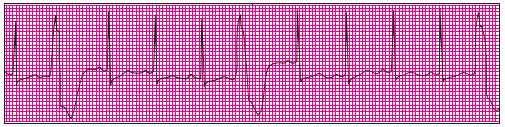

Sinus bradycardia |

| |

▪ Regular atrial and ventricular rhythms ▪ Rate less than 60 beats/minute ▪ Normal P wave preceding each QRS complex | ▪ Normal in a well-conditioned heart, as in an athlete ▪ Increased intracranial pressure; increased vagal tone from straining during defecation, vomiting, intubation, mechanical ventilation; sick sinus syndrome; hypothyroidism; inferior MI ▪ Also may occur with anticholinesterase, beta-adrenergic blocker, digoxin, and morphine use | ▪ For low cardiac output, dizziness, weakness, altered level of consciousness, or low blood pressure, follow advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocol for giving atropine ▪ Temporary pacemaker; may need evaluation for permanent pacemaker in the future |

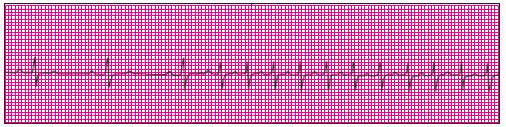

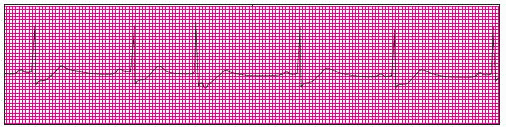

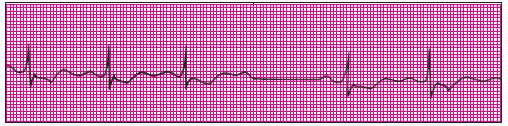

Sinoatrial (SA) arrest or block (sinus arrest) |

| |

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms normal except for missing complex ▪ Normal P wave preceding each QRS complex ▪ Pause not equal to a multiple of the previous sinus rhythm | ▪ Acute infection ▪ Coronary artery disease (CAD), degenerative heart disease, acute inferior MI ▪ Vagal stimulation, Valsalva’s maneuver, carotid sinus massage ▪ Digoxin, quinidine, or salicylate toxicity ▪ Pesticide poisoning ▪ Pharyngeal irritation from endotracheal (ET) intubation ▪ Sick sinus syndrome | ▪ Treat symptoms with atropine I.V. ▪ Temporary pacemaker, with possible permanent pacemaker for repeated episodes |

Wandering atrial pacemaker |

| |

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms vary slightly ▪ Irregular PR interval ▪ P waves irregular with changing configuration, indicating that they aren’t all from SA node or single atrial focus; may appear after the QRS complex ▪ QRS complexes of uniform shape but irregular rhythm | ▪ Rheumatic carditis from inflammation in SA node ▪ Digoxin toxicity ▪ Sick sinus syndrome | ▪ No treatment if patient is asymptomatic ▪ Treatment of underlying cause if patient is symptomatic |

Premature atrial contraction (PAC) |

| |

▪ Premature, abnormal-looking P waves that differ in configuration from normal P waves ▪ QRS complexes after P waves, except in very early or blocked PACs ▪ P wave commonly buried in or identifiable in the preceding T wave | ▪ Coronary or valvular heart disease, atrial ischemia, coronary atherosclerosis, heart failure, acute respiratory failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), electrolyte imbalance, and hypoxia ▪ Digoxin toxicity; use of aminophylline (Phyllocontin), adrenergics, or caffeine ▪ Anxiety | ▪ Usually no treatment ▪ Treatment of underlying cause if patient is symptomatic |

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia |

| |

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms regular ▪ Heart rate greater than 160 beats/minute; rarely exceeds 250 beats/minute ▪ P waves regular but aberrant; difficult to differentiate from preceding T wave ▪ P wave preceding each QRS complex ▪ Sudden onset and termination of arrhythmia ▪ With normal P wave, called paroxysmal atrial tachycardia; without normal P wave, called paroxysmal junctional tachycardia | ▪ Intrinsic abnormality of atrioventricular (AV) conduction system ▪ Physical or psychological stress, hypoxia, hypokalemia, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, MI, valvular disease, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, cor pulmonale, hyperthyroidism, and systemic hypertension ▪ Digoxin toxicity; use of caffeine, marijuana, or other central nervous system stimulant | ▪ Immediate cardioversion if patient is unstable ▪ Vagal stimulation, Valsalva’s maneuver, carotid sinus massage if patient is stable ▪ Adenosine (Adenocard) by rapid I.V. bolus injection to rapidly convert arrhythmia ▪ Calcium channel blockers or beta-adrenergic blockers. ▪ If QRS is wide, the patient may require amiodarone (Cordarone) and synchronized cardioversion. |

Atrial flutter |

| |

▪ Atrial rhythm regular and 250 to 400 beats/minute ▪ Ventricular rate variable, depending on degree of AV block (usually 60 to 100 beats/minute) ▪ Sawtooth P wave configuration possible (F waves) ▪ QRS complexes of uniform shape but usually irregular rate | ▪ Heart failure, tricuspid or mitral valve disease, pulmonary embolism, cor pulmonale, inferior MI, and carditis ▪ Digoxin toxicity | ▪ Immediate cardioversion if patient is unstable with a ventricular rate greater than 150 beats/minute ▪ Calcium channel blockers, beta-adrenergic blockers, or antiarrhythmics if patient is stable ▪ Anticoagulation therapy may be needed |

Atrial fibrillation |

| |

▪ Atrial rhythm grossly irregular; rate greater than 400 beats/minute ▪ Ventricular rhythm grossly irregular ▪ QRS complexes of uniform configuration and duration ▪ PR interval indiscernible ▪ No P waves or P waves that appear as erratic, irregular, baseline fibrillatory waves | ▪ Heart failure, COPD, thyrotoxicosis, constrictive pericarditis, ischemic heart disease, sepsis, pulmonary embolus, rheumatic heart disease, hypertension, mitral stenosis, atrial irritation, complication of coronary bypass or valve replacement surgery | ▪ Immediate cardioversion if patient is unstable with a ventricular rate greater than 150 beats/minute ▪ Calcium channel blockers, beta-adrenergic blockers, digoxin, procainamide (Pronestyl), quinidine, ibutilide (Corvert), or amiodarone if patient is stable ▪ Anticoagulation to prevent emboli ▪ Possible dual-chamber atrial pacing, implantable atrial pacemaker, or surgical maze procedure |

Junctional rhythm |

| |

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms regular ▪ Atrial rate 40 to 60 beats/minute ▪ Ventricular rate usually 40 to 60 beats/minute (60 to 100 beats/minute in accelerated junctional rhythm) ▪ P waves preceding, hidden in (absent), or after QRS complex; usually inverted if visible ▪ PR interval (when present) less than 0.12 second ▪ QRS complex configuration and duration normal, except in aberrant conduction | ▪ Inferior wall MI or ischemia, hypoxia, vagal stimulation, sick sinus syndrome ▪ Acute rheumatic fever ▪ Valve surgery ▪ Digoxin toxicity | ▪ Correction of underlying cause ▪ Atropine for symptomatic slow rate ▪ Pacemaker insertion if patient is refractory to drugs ▪ Discontinuation of digoxin if appropriate |

Premature junctional contraction |

| |

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms irregular ▪ P waves inverted; may precede, be hidden within, or follow QRS complex ▪ PR interval less than 0.12 second if P wave precedes QRS complex ▪ QRS complex configuration and duration normal | ▪ MI or ischemia ▪ Digoxin toxicity and excessive caffeine or amphetamine use | ▪ Correction of underlying cause ▪ Discontinuation of digoxin if appropriate |

Junctional tachycardia |

| |

▪ Atrial rate greater than 100 beats/minute ▪ P wave possibly absent, hidden in QRS complex, or preceding T wave ▪ Ventricular rate greater than 100 beats/minute ▪ P wave inverted ▪ QRS complex configuration and duration normal ▪ Onset of rhythm commonly sudden, occurring in bursts | ▪ Myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, inferior MI or ischemia, acute rheumatic fever, complication of valve replacement surgery ▪ Digoxin toxicity | ▪ Cardioversion if ventricular rate is greater than 150 or if patient is symptomatic ▪ Amiodarone, beta-adrenergic blockers, or calcium channel blockers if patient is stable ▪ Discontinuation of digoxin if appropriate |

First-degree AV block |

| |

▪ Atrial and ventricular rhythms regular ▪ PR interval greater than 0.2 second ▪ P wave preceding each QRS complex ▪ QRS complex normal | ▪ Inferior wall MI or ischemia, hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hyperkalemia ▪ Digoxin toxicity; use of quinidine, procainamide, beta-adrenergic blockers, calcium channel blockers, or amiodarone | ▪ Correction of underlying cause ▪ Possibly atropine if PR interval exceeds 0.26 second and symptomatic bradycardia develops ▪ Cautious use of digoxin, calcium channel blockers, and beta-adrenergic blockers |

Second-degree AV block Mobitz I (Wenckebach’s) |

| |

▪ Atrial rhythm regular ▪ Ventricular rhythm irregular ▪ Atrial rate exceeds ventricular rate ▪ PR interval progressively, but only slightly, longer with each cycle until QRS complex disappears (dropped beat); PR interval shorter after dropped beat | ▪ Inferior wall MI, cardiac surgery, acute rheumatic fever, vagal stimulation ▪ Digoxin toxicity; use of propranolol (Inderal), quinidine, or procainamide | ▪ Treatment of underlying cause ▪ Atropine or temporary pacemaker for symptomatic bradycardia ▪ Discontinuation of digoxin if appropriate |

Second-degree AV block Mobitz II |

| |

▪ Atrial rhythm regular ▪ Ventricular rhythm regular or irregular, with varying degree of block ▪ P-P interval constant ▪ QRS complexes periodically absent | ▪ Severe CAD, anterior wall MI, acute myocarditis ▪ Digoxin toxicity | ▪ Atropine, epinephrine, and dopamine for symptomatic bradycardia ▪ Temporary or permanent pacemaker for symptomatic bradycardia ▪ Discontinuation of digoxin if appropriate |

Third-degree AV block (complete heart block) |

| |

▪ Atrial rhythm regular ▪ Ventricular rhythm regular and rate slower than atrial rate ▪ No relation between P waves and QRS complexes ▪ No constant PR interval ▪ QRS interval normal (nodal pacemaker) or wide and bizarre (ventricular pacemaker) | ▪ Inferior or anterior wall MI, congenital abnormality, rheumatic fever, hypoxia, postoperative complication of mitral valve replacement, Lev’s disease (fibrosis and calcification that spreads from cardiac structures to conductive tissue), Lenegre’s disease (conductive tissue fibrosis) ▪ Digoxin toxicity | ▪ Atropine, epinephrine, and dopamine for symptomatic bradycardia ▪ Temporary or permanent pacemaker for symptomatic bradycardia |

Premature ventricular contraction (PVC) |

| |

▪ Atrial rhythm regular ▪ Ventricular rhythm irregular ▪ QRS complex premature, usually followed by a complete compensatory pause ▪ QRS complex wide and distorted, usually exceeding 0.14 second ▪ Premature QRS complexes occurring singly, in pairs, or in threes; alternating with normal beats; focus from one or more sites ▪ Ominous when clustered, multifocal, with R wave on T pattern | ▪ Heart failure; old or acute myocardial ischemia, infarction, or contusion; myocardial irritation by ventricular catheter, such as a pacemaker; hypercapnia; hypokalemia; hypocalcemia ▪ Drug toxicity (cardiac glycosides, aminophylline, tricyclic antide-pressants, beta-adrenergic blockers [or dopamine]) ▪ Caffeine, tobacco, or alcohol use ▪ Psychological stress, anxiety, pain, exercise | ▪ If warranted, procainamide, lidocaine, or amiodarone I.V. ▪ Treatment of underlying cause ▪ Discontinuation of drug causing toxicity ▪ Potassium chloride I.V. if PVC induced by hypokalemia ▪ Magnesium sulfate I.V. if PVC induced by hypomagnesemia |

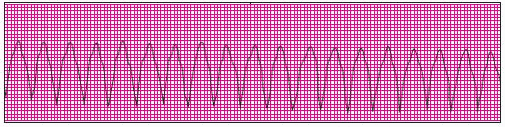

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) |

| |

▪ Ventricular rate 140 to 220 beats/minute, regular or irregular ▪ QRS complexes wide, bizarre, and independent of P waves ▪ P waves not discernible ▪ May start and stop suddenly | ▪ Myocardial ischemia, infarction, or aneurysm; CAD; rheumatic heart disease; mitral valve prolapse; heart failure; cardiomyopathy; ventricular catheters; hypokalemia; hypercalcemia; pulmonary embolism ▪ Digoxin, procainamide, epinephrine, or quinidine toxicity ▪ Anxiety | ▪ Pulseless: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR); ACLS protocol for defibrillation, ET intubation, and administration of epinephrine or vasopressin followed by amiodarone or lidocaine; if ineffective, possibly magnesium sulfate ▪ With pulse:If hemodynamically stable, ACLS protocol for administration of amiodarone; if ineffective, synchronized cardioversion |

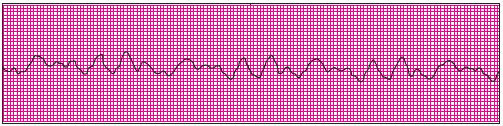

Ventricular fibrillation |

| |

▪ Ventricular rhythm and rate rapid and chaotic ▪ QRS complexes wide and irregular ▪ No visible P waves | ▪ Myocardial ischemia or infarction, R-on-T phenomenon, untreated VT, hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, alkalosis, electric shock, hypothermia ▪ Digoxin, epinephrine, or quinidine toxicity | ▪ Pulseless: CPR; ACLS protocol for defibrillation, ET intubation, and administration of epinephrine or vasopressin, lidocaine, or amiodarone; if ineffective, possibly magnesium sulfate |

Asystole |

| |

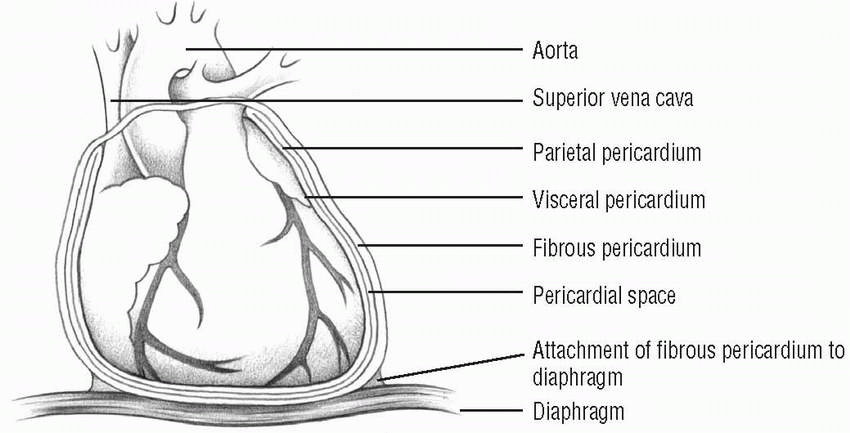

▪ No atrial or ventricular rate or rhythm ▪ No discernible P waves, QRS complexes, or T waves | ▪ Myocardial ischemia or infarction, aortic valve disease, heart failure, hypoxemia, hypokalemia, severe acidosis, electric shock, ventricular arrhythmias, AV block, pulmonary embolism, heart rupture, cardiac tamponade, hyperkalemia, electromechanical dissociation ▪ Cocaine overdose | ▪ CPR; ACLS protocol for ET intubation, transcutaneous pacing, and administration of epinephrine or vasopressin; possible atropine |

|

|