Fig. 10.1

Examples of ogive “S”-shaped learning curve and plateau with incremental gain and occasional dip (Courtesy of Dr. Henri G. Colt, MD)

Bronchoscopy-Related Education Literature

The bronchoscopy-related literature is gradually supporting the paradigm shift whereby patients will no longer bear the burden of procedure-related training. In a review of 10 papers pertaining to the use of simulation for bronchoscopy education, we noted that simulation was demonstrated to help learners improve procedural efficiency and economy of movement, thoroughness, and accuracy of airway examination and decrease airway wall trauma. In addition to increasing learner satisfaction and interest, simulated environments create opportunities where tasks can be practiced repeatedly, risks to patients are eliminated, and training scenarios can be tailored to individual learners’ needs. Both lo- and hi-fidelity simulation have been shown to enhance physician competency in procedural skills while saving time and improving the learning curve. While not yet shown conclusively in bronchoscopy, procedural skills acquired through practice on simulators are transferable to the clinical setting. In addition, simulator training with objective assessment and feedback identifies errors and provides opportunities for repeated and focused practice without exposing patients to unnecessarily prolonged procedures and discomfort.

Hi-fidelity simulation platforms using three-dimensional virtual anatomy and force-feedback technology can be used, for example, to teach conventional transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA), although less expensive, lo-fidelity models comprised of molded silicone or excised animal airways are also effective. We demonstrated the efficacy of a lo-fidelity hybrid airway model made of a porcine trachea and a plastic upper airway for learning transcarinal and transbronchial needle aspiration. This model gave learners an opportunity to practice needle insertion, positioning, safety measures, and communication with ancillary personnel. This model has since been modified so that a plastic airway is used, obviating the need for discarded animal parts and making the use of such training materials possible in hotel conference centers and nonhospital facilities. Models can be used to teach scope manipulation and airway anatomy, foreign-body removal, bronchoscopic intubation, endobronchial ultrasound-guided TBNA, and various other interventional techniques (Fig. 10.2). In fact, based on learner and instructor perceptions, a lo-fidelity model was shown to be superior to costly hi-fidelity computer simulation for learning three different conventional TBNA techniques.

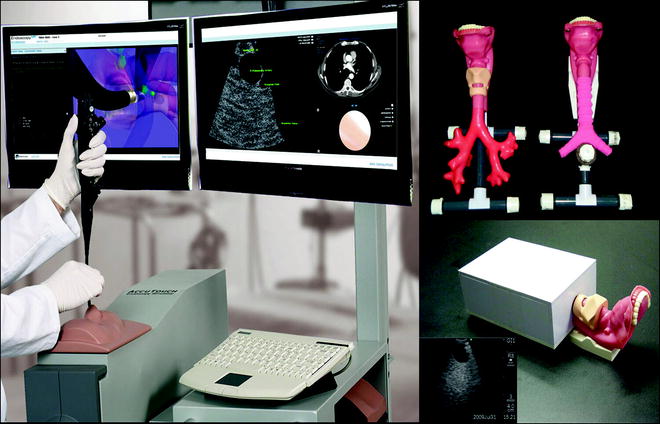

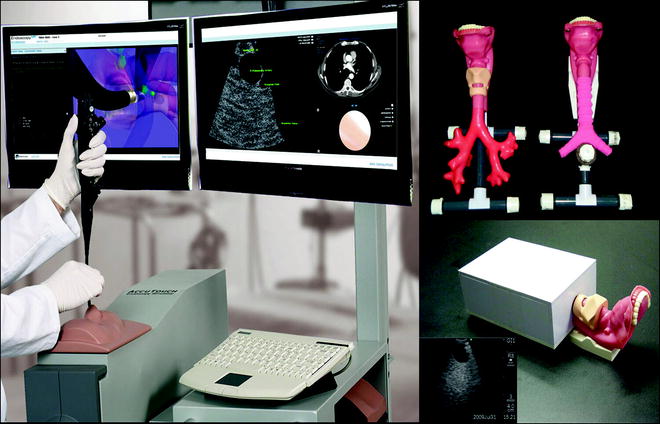

Fig. 10.2

Examples of hi-fidelity and lo-fidelity models for teaching bronchoscopic inspection, conventional transbronchial needle aspiration, and endobronchial ultrasound (Courtesy of Dr. Henri G. Colt, M.D.)

Demonstrating improvements in technical skill complete only part of the picture. The increasing emphasis on competency-oriented education also warrants that bronchoscopy courses use competency-based measures to assess the efficacy of course curricula and training modalities. Outcome measures might take the form of high- or low-stakes testing in the various cognitive, technical, affective, and experiential elements of procedure-related knowledge. Using quasiexperimental study design and a series of pretest/posttest assessments with calculations of absolute, relative, and class-average normalized gain, we have demonstrated the efficacy of a 1-day structured curriculum including didactic lectures, workshops, and hands-on simulation-based training. Studies are ongoing to determine how various elements of knowledge can be assessed using components of the Bronchoscopy Education Project described later in this chapter3 (Figs. 10.3, 10.4, and 10.5).

Fig. 10.3

Example of Bronchoscopy step-by-step instruction. Colt HG. Bronchoscopy Lessons. Instructional video pertaining to various aspects of bronchoscopy You Tube (posted 2010): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phRv73Ik7fI&feature=related (Courtesy of Dr. Henri G. Colt, M.D.)

Fig. 10.4

Example of checklist used as part of The Bronchoscopy Education Project. See Colt HG. Bronchoscopy Education Project Rationale. Instructional video You Tube, posted July 2010: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogRixvyTYEA (Courtesy of Dr. Henri G. Colt, M.D.)

Fig. 10.5

Deconstruction of a bronchoscopic procedure to enhance patient-centered learning and educational interventions within the learner’s zone of proximal development (Courtesy of Dr. Henri G. Colt, M.D.)

Description of a Transnational Education Initiative

The Bronchoscopy Education Project4 entails the design, development, and dissemination of a series of structured, uniform curricula that include required reading assignments, simulation scenarios, standardized didactic lecture material, validated assessment tools, and checklists (Fig. 10.3). The purpose of this project, officially endorsed by several international bronchology and interventional pulmonology societies, is to provide bronchoscopy educators and training program directors with competency-oriented tools and materials with which to help train bronchoscopists and assess progress along the learning curve from novice to competent practitioner. Material can be incorporated in whole or in part, as needed by each program. Learning is based on the review of written materials, focused practice during hands-on programs and during the course of subspecialty training, and through easy access to educational materials as available at specifically designed websites, YouTube, and Facebook.

In addition to many written materials and structured didactic lectures provided through regional on-site programs, a free, web-based six-part curriculum is being developed with the assistance of numerous experts from around the globe. Procedures are deconstructed into three elements: strategy and planning, technical skills, and outcomes assessment (results, quality control, ability to respond to complications, and long-term management). In order to identify elements crucial to medical reasoning when entertaining a bronchoscopy consultation, these elements are further divided into four categories using a four-box Practical approach to procedural decision making: patient evaluation, procedural strategies, techniques, and outcomes. A series of practical approach exercises is one of the six elements of the web-based curriculum. Other elements are:

The web-based Essential Bronchoscopist © and EBUS Bronchoscopist © comprised of specific reading materials, learning objectives, and post tests. Each module contains numerous question-answer sets with information pertaining to the major topics relating to bronchoscopic procedures (anatomy and airway abnormalities, patient preparation, indications, contraindications and complications, techniques and solutions to technical problems, disease states, imaging, procedural techniques, anesthesia and medications, equipment and its maintenance, as well as history and education). The aim of these modules is not to replace but to complement the subspecialty bronchoscopy training environment and motivate learners to ask questions of their preceptors and colleagues.

A Bronchoscopy Step-by-Step © and EBUS Step-by-Step © series of graded exercises help learners acquire the technical skills necessary for basic diagnostic bronchoscopy. Instructional videos are readily viewable on desktop computers as well as handheld devices, IPADs, or cell phones. Specific training maneuvers help the learner practice incrementally difficult steps of bronchoscopy and EBUS-TBNA. Steps are designed to enhance the development of “muscle memory” by breaking down complex moves into constituent elements and practicing the separate elements repeatedly before gradually combining them into more complex maneuvers.

A series of Bronchoscopy Assessment Tools © provide objective measures with demonstrated validity and interobserver reliability. Fixed numeric and grade scores can be attributed to the learner based on technical skills that include dexterity, accuracy, anatomic recognition and navigation, posture and position, economy of movement, and atraumatic instrument manipulation, pattern recognition, and image analysis.

Two additional elements are The Art of Bronchoscopy © and BronchAtlas © series of PowerPoint presentations pertaining to airway pathology, normal airway examination, and techniques of basic diagnostic and therapeutic bronchoscopic procedures. The goal is to provide free access to edited images and scientific content so that bronchoscopists might freely use materials for their own education and also to facilitate their efforts while preparing lectures within their own institutions and national societies, thereby increasing awareness of both the art and science of bronchoscopy in their communities.

Learner-Teacher Interactions Define Bronchoscopy Education

The experiential learning necessary to become a competent bronchoscopist includes passive experiences (something that happens to or is delivered onto the learner) and interactive processes (something in which the learner is actively engaged mentally, physically, and emotionally). Dewey called this learner-focused activity “learning by doing,” also suggesting that thinking is stimulated by problems the learner is interested in solving. For medical practitioners dedicated to the health and well-being of their patients, learning in this way obviously creates intrinsic value and serves to enhance the learning process.5

As our understanding of what we are doing increases and as we move toward becoming one with the activity at hand, we can become increasingly aware of the intrinsic value of that activity in our lives. Wolfgang Kohler, a German Gestalt psychologist (1887–1967) noted that such insight, defined as a way for “seeing” the link between certain ideas, is crucial to the learning process because learning is more than the simple reinforcement of our operant behaviors.

For unspecified reasons, physicians are expected to be good mentors and effective instructors without ever having learned to teach. Such an approach to the learning process runs contrary to practice in other fields (such as public school education, hobbies, or sports) and represents a significant shortcoming of our academic institutions and profession. As knowledge becomes more universally available, the attitudes and behaviors of health-care providers will change accordingly not only toward patients but also toward the next generation of medical practitioners. Learners are already less dependent on rote memorization, referring frequently to web-based instruction, electronic information delivery systems, and social media available through their computers or handheld devices. Educators will need to become more proficient at the delivery of educational materials and focus on global measures of competency and professionalism that reflect more than might simple grade scores on a multiple-choice examination. An emerging interest in new leadership development programs, specifically designed train-the-trainer seminars, and well-planned teaching scenarios that allow bronchoscopy educators to become familiar with and experiment with various educational approaches, therefore, will likely improve the educational process for physicians-in-training as well as for experienced bronchoscopists desiring to master a new procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree