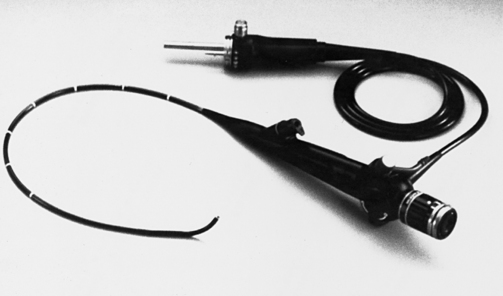

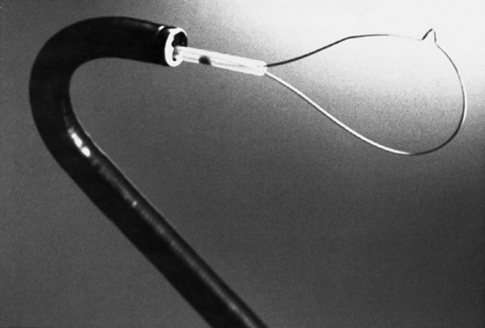

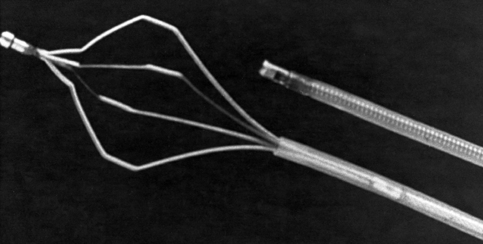

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: 1. Define the basic terms used with endoscopy. 2. Describe the characteristics and capabilities of the flexible bronchoscope. 3. Identify common indications for bronchoscopy. 4. Distinguish diagnostic and therapeutic indications for bronchoscopy. 5. Explain the uses of bronchoalveolar lavage, brushings (both sterile and nonsterile), and forceps and needle biopsies. 6. Discuss the major concepts of interventional bronchoscopy. 7. Discuss the complications of flexible bronchoscopy and the relative risks involved in the procedure. 8. Identify the contraindications to performing a bronchoscopy. 9. List the essential equipment needed to perform a bronchoscopy safely. 10. Review the role of the respiratory therapist in bronchoscopy. 11. Discuss step-by-step preparation of the patient and the equipment for the bronchoscopy. In most institutions, flexible bronchoscopy is performed by a properly trained and licensed physician (usually a pulmonologist, but sometimes a surgeon or a critical care physician) and one or two assistants, usually a respiratory therapist (RT) or a registered nurse (RN). For the remainder of this chapter, we refer to the physician performing the procedure as “the bronchoscopist” and the RN or the RT assisting as “the assistant.” In many teaching institutions, students, medical residents, or other trainees may also be present and participate in various parts of the procedure under the supervision of a licensed health care provider. Sometimes, a radiology technician is available to perform fluoroscopy (see the discussion on fluoroscopy later in this chapter or in Chapter 10), as well as a histology technician to evaluate the quality of the specimen from biopsy or brushings. RTs are educated and trained about flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopes because they often maintain the equipment and the materials needed for the procedure. The RT has become indispensable in helping the physician perform the procedure both in hospitals and outpatient clinics. The standard flexible bronchoscope has an external diameter of 5.3 mm and a total length of 605 mm (Fig. 17-1). It can pass easily down the trachea (first-order bronchus) and into the right or left mainstem bronchus. From there, it can be advanced through most fourth-order bronchi and one third of all fifth-order bronchi (Fig. 17-2). Visualization of half of the lung’s sixth-order bronchi is possible. Ultrathin scopes with a 2.7-mm external diameter and 0.8-mm biopsy channels will pass down 3.5-mm or larger endotracheal tubes, making it easier to study and perform biopsies on infants and children who are intubated. One must keep in mind that even with such depth of visualization, bronchoscopy still allows examination of only a small percentage of all airways. For comparison, colonoscopy allows the entire length of the colon to be examined during the procedure. Patients accidentally inhale a remarkable variety of objects, including corn, peas, beans, peanuts, garlic cloves, teeth, dental crowns, dental fillings, dental drill bits, pills, coins and, beads. These objects, as well as mucous plugs or clots, can be retrieved with a bronchoscope. In some cases, these items or conditions do not show up on the chest radiograph, and their discovery by bronchoscopy is based on the patient’s history or is an unexpected discovery during an evaluation for chronic cough. Grasping forceps and snares can be used with the bronchoscope to retrieve foreign objects (Figs. 17-3 and 17-4). Grasping forceps are available with rubber tips for needle and nail removal; basket types for removal of marbles, seeds, and nuts; “pelican” types for removal of food particles; and W-shaped forceps for the removal of coins. There are two basic categories of indications for flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy: diagnostic and therapeutic (Box 17-1). The flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope is used most often for diagnostic purposes, with therapeutic indications being less common. The most common indication for flexible bronchoscopy is to diagnose the cause of an abnormality seen on a chest radiograph. These abnormalities include infiltrates of any size or location, atelectasis, or mass lesions. These lesions are of particular concern if recently they have appeared on the chest radiograph, or if the patient has risk factors for malignancy, such as history of previous cancer diagnosis or history of smoking. Bronchoscopy may be indicated in the patient with a normal chest radiograph if the patient has symptoms of chronic cough, stridor, hoarseness, or history of choking. Naturally, large lesions that are in the central airways are easy to find and excise for biopsy. However, coin lesions are often in the lung periphery and cannot be seen through a flexible bronchoscope. Fluoroscopy is used to aim the tip of the bronchoscope toward the lesion (see Chapter 10 on chest imaging for the utility and limitations of the fluoroscopy). Biopsy forceps can then be advanced into the appropriate subsegmental bronchus to reach the lesion and snip off pieces to be sent for analysis. New advanced bronchoscopy techniques such as ENB and EBUS increase the likelihood of obtaining adequate tissue sample. During ENB, the patient’s lungs and the lesion are mapped out using conventional CT scan, and then the software guides the bronchoscope toward the lesion even when the lesion cannot be directly visualized. During EBUS, the ultrasound probe that is mounted on a special bronchoscope guides the biopsy needle into the submucosal lymph nodes that cannot otherwise be seen. Usually, the patient with hemoptysis coughs up small amounts of blood and then stops. Occasionally, massive hemoptysis (>200 mL/24 hours) occurs, making intervention more urgent. Large-bore rigid bronchoscopes (Figs. 17-5 and 17-6

Bronchoscopy

Characteristics and Capabilities of the Bronchoscope

Indications for Bronchoscopy

Nodules and Masses

Hemoptysis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Bronchoscopy