Bronchodilators and Bronchial Challenge Testing

When a patient undergoes pulmonary function tests for the first time, it is almost always worthwhile to have spirometry performed before and after the administration of an inhaled bronchodilator.

5A. Reasons for Bronchodilator Testing

Administering a β2 agonist is rarely contraindicated. Ipratropium bromide can be used if the β2 agonist is contraindicated. The major values of bronchodilator testing are as follows:

1. If the patient shows a positive response (see Section 5C), one is inclined to treat more aggressively with bronchodilators and possibly with inhaled corticosteroids. The improvement can be shown to the patient, and compliance is thus often improved. However, even if no measurable improvement occurs, a therapeutic trial (2 weeks) of an inhaled bronchodilator in patients with obstructive disease may provide symptomatic and objective improvement.

2. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who acutely show a heightened response to a bronchodilator have been found to have an accelerated decrease in pulmonary function over time. In such cases, aggressive therapy of the COPD seems warranted.

PEARL: Some pulmonologists believe that a positive response to a bronchodilator in COPD warrants a trial of inhaled corticosteroid therapy. However, bronchodilator response does not predict response to inhaled corticosteroid. Inhaled corticosteroid therapy is indicated for patients with moderate-to-severe COPD (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] <80% predicted) with frequent (more than once a year) or recent exacerbations. This therapy reduces the frequency of exacerbations and improves symptoms and quality of life.1,2

3. Possibly the most important result is the detection of unsuspected asthma in a person with low-normal results on spirometry.

5B. Administration of Bronchodilator

The agent can be administered either by a nebulizer unit or by the use of a metered-dose inhaler. The technique for the inhaler is described in Figure 5-1.

Ideally, the patient should not have used a bronchodilator before testing. Abstinence of 6 hours from the inhaled β2 agonists and anticholinergics and

12 hours from long-acting β2 agonists (salmeterol or formoterol) and methylxanthines is recommended. The technician should always record whether the medications were taken and the time at which they were last taken. Use of corticosteroids need not be discontinued.

12 hours from long-acting β2 agonists (salmeterol or formoterol) and methylxanthines is recommended. The technician should always record whether the medications were taken and the time at which they were last taken. Use of corticosteroids need not be discontinued.

5C. Interpretation of Bronchodilator Response

The American Thoracic Society defines a significant bronchodilator response as one in which the FEV1 or the forced expiratory vital capacity (FVC) or both increase by 12% and at least 200 mL.

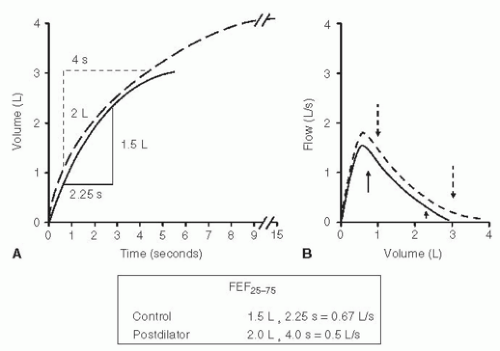

PEARL: To evaluate whether the increase in FVC is merely the result of a prolonged effort, overlay the control and postdilator curves so that the starting volumes are the same, as in Figure 5-2B. If there is a slight increase in flow, then the increase in FVC is not due to prolonged effort alone.

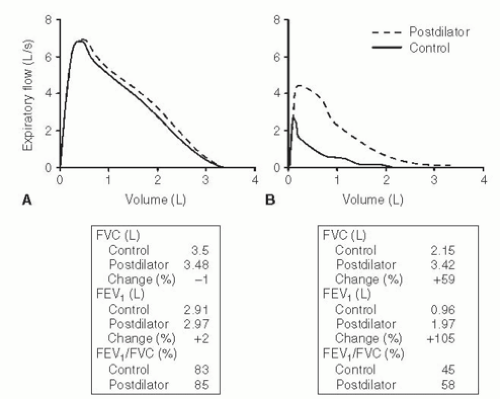

The forced expiratory flow rate over the middle 50% of the FVC (FEF25-75) is a useful measure of airway obstruction. It is not a reliable indicator of an acute change in maximal expiratory flow, however, because of the way it is affected by changes in the FVC, as shown in Figure 5-2. Typical normal and abnormal responses to inhaled bronchodilator are shown in Figure 5-3.

FIG. 5-2. By definition, the FEF25-75 (forced expiratory flow rate) is measured over the middle 50% of the vital capacity (A). The spirograms and flow-volume curves show an increase in both flow and volume after use of a bronchodilator. Yet the control FEF25-75 (0.67 L/s) is higher than the postdilator value (0.5 L/s). The reason for this apparent paradox can be appreciated from the flow-volume curves (B). The solid arrows indicate the volume range over which the control FEF25-75 is calculated. The dashed arrows show the volume range over which the postdilator FEF25-75 is calculated. The flows are lower at the end of the 25% to 75% volume range on the postdilator curve than those on the control curve. More time is spent at the low flows, which, in turn, causes the postdilator FEF25-75 to be lower than the control value. Recommendation: Do not use the FEF25-75 to evaluate bronchodilator response. Instead use the forced expiratory volume in 1 second and always look at the curves. |

5D. Effect of Effort on Interpretation

In routine spirometry, changing effort can have a misleading effect on the FEV1 and flow-volume curve. This has been discussed in Chapter 3, Section 3G. In Figure 5-4 the same subject has made two consecutive acceptable FVC efforts. During one effort (curve a), the subject made a maximal effort with a high peak flow and sustained maximal effort throughout the breath. However, in another effort (curve b), the subject exhaled with slightly less than the maximal force. The peak expiratory flow was slightly lower on curve b, but the flow on curve b exceeded that on curve a at lower volumes. The circles include the FEV1. In this situation, the slightly less forceful effort produced an FEV1 of 2.5 L compared with 2.0 on a, a difference of 25%. This result could be interpreted as a significant bronchodilator effect had one been given. Clearly, the subject’s lungs and airways have not changed, however.

There is a physiologic explanation for this apparent paradox, and the interested reader is referred to Krowka and associates.3 It is important that

one be alert to this potentially confusing occurrence, which can be very marked in patients with obstructive lung disease. The best way to minimize this problem is to require that all flow-volume curves have sharp peak flows, as in curve a in Figure 5-4, especially when two efforts are compared. Short of that, the peak flows should be very nearly identical (<10% to 15% difference). The principle also applies to bronchial challenge testing (see below). This paradoxical behavior can easily be identified from flow-volume curves; it is almost impossible to recognize it from volume-time graphs.

one be alert to this potentially confusing occurrence, which can be very marked in patients with obstructive lung disease. The best way to minimize this problem is to require that all flow-volume curves have sharp peak flows, as in curve a in Figure 5-4, especially when two efforts are compared. Short of that, the peak flows should be very nearly identical (<10% to 15% difference). The principle also applies to bronchial challenge testing (see below). This paradoxical behavior can easily be identified from flow-volume curves; it is almost impossible to recognize it from volume-time graphs.

FIG. 5-3. Responses to inhaled bronchodilator. (A) Normal response with -1% change in the forced expiratory vital capacity (FVC) and +2% change in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). (B) Positive response with a 59% increase in the FVC and a 105% increase in the FEV1. The FEV1/FVC ratio is relatively insensitive to this change and therefore should not be used to evaluate bronchodilator response.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|