Chapter 18 Bronchiectasis, primary ciliary dyskinesia and cystic fibrosis

BRONCHIECTASIS

For many years, non-cystic fibrosis (CF) bronchiectasis has been a poorly evaluated condition for which management has been somewhat empirical and the patients have been included in a general respiratory clinic. The British Thoracic Society Bronchiectasis Guidelines (2007) have been developed with three aims:

With over a thousand references, these guidelines are an excellent resource for managing non-CF bronchiectasis. The recently published guidelines by the American College of Physicians have emphasized the paucity of evidence-based clinical information for the management of non-CF bronchiectasis (Rosen 2006).

‘Bronchiectasis’ is the term used for permanent dilatation of one or more bronchi, whereby the elastic and muscular tissue of the bronchial walls is destroyed by acute or chronic infection (Cole 1995). This damage leads to impaired drainage of bronchial secretions. These secretions often become chronically infected, producing a persistent host inflammatory response. The combination of infection and a chronic inflammatory host response results in a progressive destructive lung disease. Depending upon the aetiology, bronchiectasis can affect specific lobes or both lungs.

The incidence and prevalence of bronchiectasis are unknown. Chest radiography — although usually the first investigation — is an insensitive method for evaluating bronchiectasis. Computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard in the detection of bronchiectasis (Smith & Flower 1996), but population screening using CT is not justified. With the decline in childhood tuberculosis, measles and whooping cough there is an impression that bronchiectasis is less prevalent. However, treatment of bronchiectasis has improved and it is important to try and establish the exact cause. Diagnosing the cause may define a specific approach to treatment and provide a prognosis as in the case of cystic fibrosis. A survey of the causative factors of bronchiectasis identified that 29% of cases were post infectious, 8% due to an immune defect and 7% due to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), but for 53% of patients no cause was found (Pasteur et al 2000). A list of the common causes of bronchiectasis is set out in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 Common causes of bronchiectasis

| Post-infective | |

| Mucociliary clearance defects | |

| Immune defects | |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis | |

| Localized bronchial obstruction | |

| Gastric aspiration |

Diagnosis and investigations

The chest radiograph may be normal or there may be signs of thickened bronchial walls (tramlining), crowding of vessels with loss of volume and cyst-like shadows with fluid levels. The chest radiograph on its own is an insensitive test, detecting less than 50% of patients with bronchiectasis (Currie et al 1987).

The chest radiograph may be normal or there may be signs of thickened bronchial walls (tramlining), crowding of vessels with loss of volume and cyst-like shadows with fluid levels. The chest radiograph on its own is an insensitive test, detecting less than 50% of patients with bronchiectasis (Currie et al 1987). High-resolution CT is the imaging method of choice as a diagnostic tool in bronchiectasis. It has a high specificity, greater than 90% (Smith & Flower 1996).

High-resolution CT is the imaging method of choice as a diagnostic tool in bronchiectasis. It has a high specificity, greater than 90% (Smith & Flower 1996). Sputum specimens for examination and culture to identify the micro-organisms and their sensitivity to antibiotics. The most common bacteria found in bronchiectatic sputum are Haemophilus influenzae (70%), Streptococcus pneumoniae and Pseudomonas (Ps) aeruginosa. The latter is found in patients with diffuse bronchiectasis and associated with accelerated lung disease (Evans et al 1996). Patients infected with Ps. aeruginosa require a higher intensity of treatment.

Sputum specimens for examination and culture to identify the micro-organisms and their sensitivity to antibiotics. The most common bacteria found in bronchiectatic sputum are Haemophilus influenzae (70%), Streptococcus pneumoniae and Pseudomonas (Ps) aeruginosa. The latter is found in patients with diffuse bronchiectasis and associated with accelerated lung disease (Evans et al 1996). Patients infected with Ps. aeruginosa require a higher intensity of treatment. The diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is difficult. The routine investigations should include: skin prick tests, eosinophil count, Aspergillus precipitins, total IgE levels with specific IgG and IgE levels to Aspergillus. Plain radiography may show fleeting shadows responsive to steroids. CT scanning may show the typical proximal bronchiectasis.

The diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is difficult. The routine investigations should include: skin prick tests, eosinophil count, Aspergillus precipitins, total IgE levels with specific IgG and IgE levels to Aspergillus. Plain radiography may show fleeting shadows responsive to steroids. CT scanning may show the typical proximal bronchiectasis. Gene mutation analysis. This should be performed on all cases of idiopathic bronchiectasis to exclude some of the more benign mutations of cystic fibrosis (Pasteur et al 2000).

Gene mutation analysis. This should be performed on all cases of idiopathic bronchiectasis to exclude some of the more benign mutations of cystic fibrosis (Pasteur et al 2000).Medical management

Indications for antibiotics

Nebulized antibiotics may be used for patients with severe bronchiectasis whose disease is progressive and difficult to control (Currie 1997). Nebulized antibiotics can delay persistent infection with Ps. aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis if instituted at the time of first colonization (Valerius et al 1991). Although there are no randomized clinical trials, this practice may be used in bronchiectasis as acquisition of Ps. aeruginosa is associated with greater morbidity (Evans et al 1996). Randomized controlled trials, using nebulized antibiotics for bronchiectatic patients chronically infected with Ps. aeruginosa, have shown a reduction in sputum density of Ps. aeruginosa (Barker et al 2000) and a lessening of disease severity (Oriols et al 1999). Tobramycin solution for inhalation (TOBI) has been used in a pilot study in patients with severe bronchiectasis (Scheinberg & Shore 2005). Although there was an improvement in respiratory symptoms, there was a significant intolerance of the medication, with 10 withdrawals from the study (n = 41). Intravenous antibiotics are used for severe disease, patients who fail to respond to oral antibiotics and those chronically infected with Ps. aeruginosa.

Other treatment measures

Topical medication may be indicated for chronic mucopurulent rhinosinusitis and the recommended technique for inhaled topical deposition of drugs is the head-down and forward position to encourage entry of the drops to the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses (Wilson et al 1987).

Surgical resection should be considered only if the bronchiectasis is localized, but there are no randomized controlled trials to compare surgical versus conservative treatment in the decision-making process (Corless & Warburton 2000). In very severe widespread bronchiectasis with respiratory failure, lung transplantation may be considered.

The inhalation of recombinant human deoxyribonuclease (rhDNase) does not appear to improve ciliary transportability, spirometry, dyspnoea or quality of life in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis (Wills et al 1996).

Inhaled steroids have been evaluated, with a trend to improving some respiratory parameters, but larger studies are needed (Kolbe & Wells 2000). A subset of bronchiectatic patients respond to bronchodilators and all patients should be tested for a response (Hassan et al 1999).

Physiotherapy management

Excess bronchial secretions

An airway clearance technique (ACT), for example the active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT) or autogenic drainage (AD) (Chapter 5), should be introduced and self-treatment encouraged (Rosen 2006). Each patient should be assessed to determine the positions that may increase the efficiency of secretion clearance and a CT scan, if available, may facilitate this. The sitting position may be adequate for patients with minimal secretions. The horizontal position may be a more acceptable and comfortable alternative to the head-down tipped position and has been shown to be equally effective in patients who expectorate >20 g of sputum per day (Cecins et al 1999).

In patients who present with gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) there may be concern that the head-down tipped position will exacerbate the problem. The head-down tipped position is now rarely indicated. Chen et al (1998) reported no difference in the duration or frequency of symptoms in the various drainage positions. Other techniques that may be used to facilitate airway clearance have proven efficacy when used in gravity-assisted positions, e.g. Flutter and the active cycle of breathing techniques (Eaton et al 2007, Thompson et al 2002) and Acapella (Patterson et al 2004, 2005, 2007). These are discussed in Chapter 5. It has been suggested that a test of incremental respiratory endurance (TIRE) may be a useful method of airway clearance. In a single treatment session comparing the TIRE with ACBT, significantly more sputum was expectorated with ACBT (Patterson et al 2004). In contrast, Chatham et al (2004) demonstrated that TIRE was more effective than the ACBT. Further research is needed in this field.

It is important that physiotherapy techniques and positions for treatment are reassessed at regular intervals (Currie et al 1986). Most patients should be reassessed within 3 months of initial instruction and then at least annually. A diagnosis of bronchiectasis may be confirmed in the absence of a daily productive cough. For these patients it would seem advisable to teach an ACT to be used during acute exacerbations of pulmonary infection (British Thoracic Society Guidelines 2007). In some patients with bronchiectasis it may be the increase in ventilation to the bronchiectatic area (use of the dependent position) rather than any ‘drainage’ from the area in an uppermost position that will increase airway clearance. Individual assessment is imperative for effective management and the end-point of a treatment session must be recognized by self-assessment.

Hypertonic saline

Hypertonic saline has been shown to increase the ciliary transportability of bronchiectatic sputum, probably through its action of altering sputum rheology (Wills & Greenstone 2006). Kellet et al (2005) compared ACBT with three other treatment arms: ACBT preceded by nebulized terbutaline alone or in combination with either isotonic or 7% saline, in stable bronchiectatic patients producing less than 10 mg sputum per day. Hypertonic saline was shown to improve sputum weight, ease of expectoration, and lung function and reduce viscosity compared with the other treatment arms. Longer-term studies are required to determine the place of hypertonic saline on infection rates, quality of life and lung function.

Acute exacerbation of infection

Mechanical adjuncts will be required in addition to an airway clearance technique to assist the clearance of excess bronchial secretions. A nebulized bronchodilator and/or humidification (Conway et al 1992) before treatment may help in the mobilization of tenacious secretions. Intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB) may help both in the clearance of secretions and in reducing the work of breathing. Patients who, many years ago, received the more radical treatment of resection of more than one lobe will probably have very poor respiratory reserve by the time they reach middle age. A superimposed infection in these patients may precipitate respiratory failure. Modified positioning, for example side lying or high side lying, combined with IPPB may be an effective form of treatment in minimizing the effort of clearing secretions. Non-invasive ventilation (Chapter 11) may be indicated in acute respiratory failure, although the outcome may be less successful in the presence of excess bronchial secretions.

The presence of blood streaking in the sputum is not a contraindication to physiotherapy and treatment should be continued. If there is frank haemoptysis, physiotherapy should be temporarily discontinued but resumed as soon as the sputum is only mildly blood stained to avoid retention of old blood and mucus. Before discharge from hospital, it is important that the patient is able to take the responsibility for their treatment and is confident with the positions and techniques required to continue regularly at home. If a bronchodilator has been prescribed, this should be taken before treatment and a few patients with bronchiectasis may also be prescribed nebulized antibiotic drugs, which should be inhaled after airway clearance. A breath-enhanced nebulizer or adaptive aerosol delivery (AAD) device is recommended for delivery of antibiotics (Chapter 5). If a patient is on the waiting list for lung transplantation, a preoperative rehabilitation programme should be established and postoperative treatment would be as outlined in Chapter 15.

Breathlessness

A minority of patients with bronchiectasis complain of breathlessness. For these patients rest positions to relieve breathlessness and breathing control while walking and stair climbing should be included in the treatment programme (Chapter 5).

Reduced exercise tolerance

Exercise should be encouraged to improve general physical fitness. It will also assist the mobilization of bronchial secretions. Patients with severe bronchiectasis may benefit from a group pulmonary rehabilitation programme (Chapter 13). There is little research evaluating the place of exercise in bronchiectasis although there is a suggestion that inspiratory muscle training (IMT) may improve endurance exercise and quality of life (Bradley et al 2002). Newall et al (2005) evaluated an 8-week high-intensity pulmonary rehabilitation programme in combination with IMT or IMT sham or a control group. Both exercise groups showed significant improvements in exercise performance and inspiratory muscle strength. This was maintained at 3 months only in the IMT group. In the short term there would appear to be no advantage of including IMT in an exercise programme although it may prove beneficial in the longer term.

PRIMARY CILIARY DYSKINESIA

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is an autosomal recessive disorder with an incidence of between 1 in 15 000 and 1 in 30 000 (Cole 1995) and an expected prevalence of 3000 cases in the United Kingdom. Many cases are underdiagnosed. However, there is an increasing understanding of the complex genetics of PCD (Bush & Ferkol 2006) and therefore an improvement in the diagnosis and understanding of the phenotypic features (Noone et al 2004).

PCD is characterized by abnormal structure of the cilia; normal structure of the cilia but with abnormal function; absence of the cilia. These abnormalities result in recurrent infections in the nose, ears, sinuses and lungs. Fertility may be affected, both in the female because the fallopian tubes are lined with cilia and in the male due to reduced sperm motility. In 50% of cases, PCD is associated with dextrocardia or situs inversus. Kartagener described a syndrome of bronchiectasis, sinusitis and situs inversus in 1933. Later it was recognized that there was also a ciliary abnormality and this could occur without situs inversus. Cilia defects were described first in spermatozoa and later in nasal and bronchial cilia and the term ‘immotile cilia syndrome’ was applied to this group of conditions. With the discovery of a range of cilial defects, with variation in beat frequency and ultrastructure and the recognition that not all abnormal cilia are immotile, the term primary ciliary dyskinesia was adopted (Greenstone et al 1988).

The age of presentation can vary from newborn to 51 years (Turner et al 1981). Chronic sputum production and nasal symptoms are the main presenting symptoms. Other presentations include pneumonia and rhinitis in the newborn, ‘asthma’ with a productive cough, chronic and severe secretory otitis media (with associated hearing problems), severe oesophageal reflux in the older child and problems of infertility and ectopic pregnancy in the adult. Specific investigations which may clarify the diagnosis of PCD include a nasal mucociliary clearance test such as the saccharin test (Stanley et al 1984), photometric determination of ciliary beat frequency (Rutland & Cole 1980) and electron micrographic analysis. Genetic testing should be undertaken to exclude the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Exhaled and nasal nitric oxide is very low in PCD (Karadag et al 1997) but increased in bronchiectasis and asthma. Although the measurement is not recommended as a diagnostic test, if levels are low in a patient with bronchiectasis then the diagnosis of PCD should be excluded.

Medical management

Recent studies have focused on the influence of drugs on cough clearance (Houtmeyers et al 1999, Noone et al 1999). In PCD airway clearance is dependent on cough, but an increased amount of secretion is necessary to ensure effective clearance with coughing. Aerolized uridine-5′-triphosphate has been shown to improve whole lung clearance during cough after a single dose when compared to 0.12% saline (Noone et al 1999). Further trials of this drug are required to determine the clinical significance of long-term administration. Two case reports have suggested benefit from inhalation of rhDNase in the acute situation (Desai et al 1995, ten Berge et al 1999). However, its use has not been validated in PCD in a controlled trial. Inhaled b2-agonists are frequently prescribed in PCD for their effect on bronchodilation, mucociliary transport and thinning of secretions (Rubin 1988). Regular use in asthma may be associated with increased bronchial responsiveness and decreased airway calibre. Koh et al (2000) have shown that no such adverse effects or decrease in lung function were seen in PCD over a 6-week period. Severe gastro-oesophageal reflux, which can compromise airway clearance, is a problem for some patients and requires appropriate management with a proton pump inhibitor.

Physiotherapy management

Daily physiotherapy is usually necessary in the child with PCD. It is important that parents are taught to recognize signs of infection early: for example, the child may be lethargic, ‘off colour’ and feel abnormally hot (pyrexia). In a study to examine cough frequency in children who were clinically stable, parental scoring equated to ambulatory monitoring. The cough frequency was shown to correlate with inflammatory markers but not with FEV1 (Zihlif et al 2005). Physiotherapy should be increased during infective episodes and parents must understand that effective treatment is not achieved by antibiotics alone.

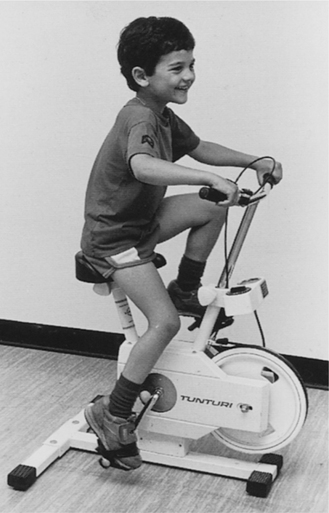

Huffing games and airway clearance devices can usually be introduced at an early age and by 8 or 9 years the child can begin to do most of the treatment themselves, gradually becoming independent. It has been suggested that the PEP mask may be a useful technique, based on the theoretical benefits of peripheral mobilization of secretions, and can be used at any age including babies (Gremmo & Guenza 1999). Some patients may require nebulized antibiotics and inhaled b2-agonists for their beneficial effect on mucociliary clearance. Beta-2 agonists should be inhaled before and antibiotics after airway clearance. Exercise, which increases bronchodilation to a greater extent than b2-agonists (Phillips et al 1996), should be encouraged from the time of diagnosis and its importance emphasized to parents and patients (Fig. 18.1). Even with grommets in place children can enjoy swimming (Pringle 1992).

Evaluation of physiotherapy

In the young patient with PCD, effective treatment in the stable condition may be recognized by the presence of only minimal coughing on exertion. During an infective episode signs and symptoms of effective treatment include a reduction in shortness of breath, coughing, wheeze and fever if either or both have been present.

CYSTIC FIBROSIS

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most frequent cause of suppurative lung disease in Caucasian children and young adults and is characterized by chronic pulmonary disease, pancreatic insufficiency and increased concentrations of electrolytes in the sweat (HØiby & Koch 1990).

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive condition most commonly found in Caucasian populations with a carrier rate of 1 in 25 and the disease occurring in approximately 1 in 2500 live births (Dodge et al 1993). Carriers of the genetic defect show no signs of cystic fibrosis, but if both parents carry the abnormal gene each child born has a 1 in 4 chance of inheriting the condition. When the condition was first described by Anderson (1938), life expectancy was less than 2 years. Increased recognition of the disease, especially in its milder forms, and improved treatment has resulted in a median age of survival of approximately 31 years (Shale 1997a). Current survival figures from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2006) report a median survival in the USA of over 35 years of age. Over the last 20 years in the Manchester Centre (United Kingdom), the number of patients living into the fourth and fifth decade of life has increased from 5% to 35%. Cohort survival graphs indicate an improvement in survival, with time, in the UK in all age groups (Dodge et al 1993). If the trend for improved survival continues, many of the patients born in 2000 now have a predicted median survival exceeding 50 years (Dodge et al 2007).

Before identification of the gene in 1989, a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis was made using the sweat test, which measures the amount of sodium in the sweat (Di Sant-Agnese & Davis 1979). The basic defect for CF lies on chromosome 7 and was identified in 1989 (Rommens et al 1989). The faulty gene in CF codes for the transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). The abnormality in this protein leads to changes in ion transport (McBride 1990), which produce changes in the nature of the mucus and serous secretions produced by the exocrine glands, cells of the respiratory system and digestive tract.

Ion transport in human airways is dominated by the absorption of sodium ions from the mucosal surface (Alton et al 1992), and this is associated with the movement of water into the epithelial cells. The balance between the movement of sodium and chloride probably determines the volume and composition of the airway surface liquid and may affect mucociliary clearance (Alton et al 1992).

It has proved extremely difficult to provide an accepted unifying hypothesis as to how defective CFTR function translates into the lethal pathophysiology of the lung. In particular, how it results in the aggressive suppurative lung disease so characteristic of CF and different from the indolent non-CF bronchiectasis. Two conflicting theories currently prevail. One is the airway surface liquid (ASL) tonicity hypothesis (Zabner et al 1998), which relates the pathophysiology to altered tonicity (high salt content) of the ASL layer. However, the weight of evidence now favours the ASL volume hypothesis, which suggests that a depletion of the volume of the ASL is a significant factor in the pathogenesis of CF pulmonary disease (Coakley & Boucher 2007).

The lungs are structurally normal at birth (Reid & De Haller 1967), but studies have demonstrated evidence of inflammation and infection in infants and children with CF (Birrer et al 1994, Khan et al 1995) and in asymptomatic adults with normal lung function (Konstan et al 1994). Infection stimulates further mucus secretion and a generalized obstructive, suppurative cycle becomes established. Repeated infections result in a neutrophil bronchiolitis. The neutrophils are ineffective at eliminating the micro-organisms which chronically infect the small airways. They break down, releasing numerous peptides, and in particular neutrophil elastase, which destroy lung tissue. The consequences are a destructive progressive suppurative bronchiectasis. The cycle of infection and inflammation impairs ciliary function and reduces mucus clearance.

Diagnosis and presentation

Newborn screening for CF is now possible and, where available, it most often uses measurement of immunoreactive trypsin (IRT) (which is abnormally high in CF) followed by DNA testing for a limited number of CFTR mutations. National newborn screening programmes for CF currently exist in New Zealand, France and Denmark, and will be available nationally in the United Kingdom by 2008. Regional or local programmes exist in parts of the United States of America, Australia and other areas of Europe. The results of a large randomized controlled trial of newborn screening for CF reported improved height, weight and head circumference in a screened group compared with a non-screened group (Farrell et al 2001) as well as higher cognitive function (Koscik et al 2004).

In the absence of newborn screening, the majority of patients continue to be diagnosed early in life with symptoms related to either the respiratory or gastrointestinal systems. Gastrointestinal abnormalities are often the earliest and most common presenting feature. The finding of echogenic bowel, during routine antenatal ultrasound, is associated with CF (although only in a minority of cases). Karyotyping and CF screening should be considered in this situation. In the neonate failure to pass meconium (meconium ileus) is the most common presenting feature, occurring in about 10–15% of cases (Park & Grand 1981). Signs of intestinal obstruction usually occur within 48 hours of birth. The infant fails to pass meconium after birth because the bowel is obstructed by sticky inspissated intestinal contents. In milder cases there may only be a delay in the passage of meconium. Blood should be taken for genotyping in infants with meconium ileus, as this condition can also occur in infants who do not have CF.

Another presenting sign in infants and young children is a voracious appetite and failure to thrive due to pancreatic insufficiency and malabsorption. Abnormalities in ion transport in the pancreas lead to inflammation and later to fibrosis of the acinar portion of the gland and to hyposecretion of the major digestive enzymes secreted by the pancreas. The presenting symptom is steatorrhoea with the passage of characteristically fatty and offensive stools. The majority of patients (85%) with CF are pancreatic insufficient (Davidson 2000). The remaining 15% usually have better nutrition and pulmonary function and a better survival prognosis. Occasionally older children present, having been managed for other respiratory conditions, for example asthma. In adulthood a late diagnosis may be made when the patient presents with infertility.

Signs and symptoms

Respiratory

The respiratory signs and symptoms of cystic fibrosis vary. The majority of older children and adults have a cough productive of sputum with varying degrees of purulence. The respiratory pathogens most commonly isolated in sputum are Pseudomonas aeruginosa (61%), Staphylococcus aureus (28.3%), Haemophilus influenzae (8.9%) and Burkholderia cepacia (3.2%) (FitzSimmons 1993). Infection with B. cepacia is often associated with accelerated pulmonary disease and a worse prognosis (Muhdi et al 1996).

Auscultation is often unrewarding when compared with the severity of radiological disease. Coarse inspira tory crackles are often heard. A pleural rub may be heard in association with infective exacerbations. The chest radiograph is often normal at birth but early changes include bronchial wall thickening, initially in the upper zones. As the disease progresses, hyperinflation may be noticeable with ill-defined nodular shadows, numerous ring and parallel line shadows indicating bronchial wall thickening and bronchiectasis (Chapter 2). High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging provides detailed evaluation of the lungs in CF (Chapter 2). Studies using HRCT in infants with CF have demonstrated early structural changes, even in those who have minimal symptoms (Long et al 2004).

Pulmonary function tests initially show signs of airways obstruction, but with advanced disease a restrictive pattern may be superimposed on the obstructive defect and a diffusion abnormality will also become apparent. Pulmonary function tests in infants with CF have shown early changes with diminished airway function soon after diagnosis, even in infants with no clinical history of clinical infection. These changes seem to persist during early childhood (Ranganathan et al 2001, 2004). More recently the use of multiple breath washout techniques to measure lung clearance index (LCI) (Chapter 3) have been shown to be effective and sensitive in terms of detecting early lung disease in cystic fibrosis (Aurora et al 2005a, Lum et al 2007). Pulmonary function measurements (FEV1, PaO2, PaCO2) have been shown to be predictors of mortality (Kerem et al 1992). As the disease progresses ventilation/perfusion imbalance occurs, leading to hypoxaemia and pulmonary hypertension. Carbon dioxide retention occurs in patients with severe disease.

Asthma is as common in patients with CF as it is among the general population. Many patients with CF have a positive skin test to Aspergillus fumigatus. This is often seen in the sputum of patients and can be isolated in 40–60% of patients (Chen et al 2001). Colonization of the lower airway with Aspergillus fumigatus and the complication of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is well recognized in patients with cystic fibrosis (Skov et al 2005) and occurs in up to 10% of patients (Mastella et al 2000). ABPA is recognized by recurrent wheezing, deteriorating chest symptoms, fleeting fluffy shadows on the chest radiograph and elevated IgE levels which are specifically raised to Aspergillus.

Gastrointestinal

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) has become a significant complication as a consequence of improved survival and is a result of progressive fibrosis damaging the endocrine cells that produce insulin (Bridges & Spowart 2006). The onset of diabetes, if not detected and treated promptly, can result in a decline in the patient’s clinical condition (Lanng et al 1992). The basic defect also affects the hepatobiliary system, which can result in a biliary cirrhosis. Patients with severe disease can develop portal hypertension. The main complication is bleeding from gastric or oesophageal varices. Liver transplantation may be required.

Other

Puberty may be delayed for both male and female patients. Most women with cystic fibrosis have normal or near-normal fertility. Improving survival has resulted in an increasing number of the female population having children. Outcome of pregnancy is improved if pulmonary function is greater than 60% predicted (Edenborough et al 1995). Pregnancy has been reported to have a slight adverse effect on the health of women with CF (Gillet et al 2002). Women with CF require a greater intensity of treatment during pregnancy (McMullen et al 2006).

Most males are infertile because of developmental defects of the vas deferens, which is either absent or blocked, but they can produce sperm. Improved technology, whereby sperm can be aspirated from either the testis or epididymal sac in conjunction with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), has resulted in CF biological fathers (Phillipson et al 2000).

Approximately one-third of adult patients with CF develop rheumatic symptoms (Bourke et al 1987). The two most common forms are an episodic and recurrent arthralgia /arthritis and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy. They are characterized by joint pain, tenderness, swelling and limitation of movement, usually symmetrical and affecting particularly the knees, ankles and wrists (Johnson & Knox 1994). More important has been the recent recognition of the high prevalence of low bone mineral density in children and adults (Bachrach et al 1994, Bhudmkanok et al 1996, Haworth et al 1999), which leads to a high incidence of fractures. Rib fractures can result in considerable pain, sputum retention and morbidity.

Medical management

Long-term oral anti-staphylococcal antibiotics are given in the early years to treat Staphylococcus aureus, which is often the main micro-organism causing chronic infection. A considerable advance over the last few years has been the introduction of the macrolides as a long-term treatment for cystic fibrosis. Although an antibiotic, it is probable that the modulatory anti-inflammatory properties of the drug are responsible for the improvement in clinical status and preserved pulmonary function demonstrated in well-conducted clinical trials (Equi et al 2002, Saiman et al 2003, Wolter et al 2002).

Subsequently patients become chronically infected with Ps. aeruginosa, which increases treatment requirements and morbidity. The practice of starting nebulized and oral antibiotics at time of first culture of Ps. aeruginosa has been shown to be effective in eradicating and delaying persistent infection (Valerius et al 1991).

Nebulized antibiotics (Webb & Dodd 1997) have been shown to be effective in the treatment of chronic Ps. aeruginosa infection (Mukhopadhyay et al 1996, Touw et al 1995). Antibiotics are usually inhaled twice daily and should follow airway clearance. For many years, colistin has been the standard drug used for nebulization but there have been no large randomized controlled trials to unequivocally demonstrate benefit. High-dose preservative-free tobramycin (TOBI) has been used for inhalation with demonstrated benefit in CF patients (Ramsey et al 1999). However, the high cost and occasional intolerance may preclude its use in all CF patients infected with Ps. aeruginosa.

Intravenous antibiotics are frequently used for acute infective exacerbations but opinions differ as to the regular or symptomatic use of intravenous antibiotics (Elborn et al 2000). Treatment usually needs to continue for at least 14 days and can be evaluated by monitoring respiratory function, sputum quantity, bodyweight, blood gases and blood inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (Hodson 1996).

Patients needing frequent or prolonged antipseudomonal treatment, and who have poor venous access, may require implantable intravenous access devices. These devices can maintain continuity of antibiotic infusions and quality of life for the patient undertaking treatment at home (Shale 1997b, Stead et al 1987).

Segregation of patients colonized with Burkholderia cepacia, from other patients with cystic fibrosis, limits the spread of the organism by social contact (Govan et al 1993, LiPuma et al 1990, Muhdi et al 1996). It is now recognized that organisms classified as B. cepacia comprise a number of distinct genomic species each known as a genomovar of the B. cepacia complex (BCC). Currently there are 10 different described genomovars in the BCC. Disease progression and survival may be influenced by the genomovar status of the CF patient (Jones et al 2004). In some units adults are segregated in outpatient clinics according to their genomovar status on the basis that some genomars are transmissible and can superinfect patients with non-transmissible genomovars (Ledson et al 1998).

Many CF units adopt a general segregation policy for outpatient clinics. This is based either according to microbiological status or on a total segregation approach (where all patients are segregated regardless of microbiological culture). Health professionals must pay particular attention to hygiene and thorough hand washing between examining patients (Cystic Fibrosis Trust 2004a).

There has been concern regarding the emergence of transmissible strains of Ps. aeruginosa in large CF centres despite the use of the correct infection control measures (Jones et al 2001, McCallum et al 2001). As a consequence, many CF clinics practice inpatient and outpatient segregation by microbiological status (Cystic Fibrosis Trust 2004b). At the Manchester Centre (United Kingdom), a 4-year prospective surveillance demonstrated ongoing transmissible Ps. aeruginosa cross-infection between inpatients despite established conventional infection control measures. As a consequence, communal areas such as the day room and kitchen were closed and the patients are now required to stay in their rooms and not mix irrespective of their individual microbiological status (Jones et al 2005).

Contamination of nebulizers is common and patients must be given instruction in the cleaning and care of nebulizer equipment. To minimize contamination, cleaning and drying of this equipment after use are essential (Hutchinson et al 1996).

As a consequence of lung infection, there are large quantities of DNA from the breakdown of inflammatory cells, e.g. neutrophils. The inhalation of rhDNase acts on the DNA in the purulent lung secretions (Range & Knox 1995). It has been shown to improve lung function (Shah et al 1996), reduce viscoelasticity of the mucus (Shah et al 1996) and decrease exacerbations of bronchopulmonary infection (Fuchs et al 1994). Occasionally alteration in voice and episodes of pharyngitis may be experienced, but these are usually minor and transient (Hodson & Shah 1995). Alternate day therapy may be as effective as daily treatment in some patients (Suri 2005).

Hypertonic saline, inhaled before physiotherapy, may also assist in clearance of secretions (Eng et al 1996, Robinson et al 1996). There is a potential logic in the use of hypertonic saline for inhalation, whereby it will restore to normal the disrupted airway surface liquid of the CF airways. Two randomized trials have shown, in a small number of CF patients, preservation of lung function and in one of the trials a reduction in infective exacerbations (Donaldson et al 2006, Elkins et al 2006a). Hypertonic saline is inexpensive, safe and there is a reasonably high level of evidence to support its use. However, it does have an unpleasant taste and adds another treatment burden to the already overloaded self-care plan of all CF patients.

In CF a high energy intake is needed as a result of malabsorption and the increased metabolic requirements during infection. The dietary energy intake should exceed the normal daily recommendation to sustain and maintain adequate weight, muscle bulk and function (Poole 1995). Supplements of fat-soluble vitamins and vitamin K are usually necessary in addition to pancreatic enzymes, which should be taken with all meals and snacks (Wolfe & Collins 2007). When nasal obstruction by polyps is incomplete, a corticosteroid nasal spray may be tried. Complete obstruction is unusual and polypectomy may be indicated.

Haemoptysis will usually stop spontaneously, but if bleeding is severe and prolonged, bronchial artery embolization by an experienced operator in a specialist centre can be a life-saving procedure (Ashleigh & Webb 2007) The current use of short courses of oral or intravenous tranexamic acid for moderate haemoptysis is effective.

Heart-lung and double lung transplantation (Chapter 15) have been successfully carried out in patients with end-stage lung disease but there is a critical shortage of donor organs. Non-invasive ventilation may be life-saving and indicated for patients developing severe respiratory failure to bridge the waiting time to transplantation (Hodson et al 1991, Madden et al 2002).

Home treatment

In many countries the emphasis on treatment is moving from hospital to home. The benefits for patients of treatment at home include less disruption to school, work and family life while avoiding the isolation from friends and family that hospitalization incurs. Increasing numbers of CF patients are receiving their intravenous antibiotics at home usually because quality of life is better, but clinical outcome is better for the patient treated in hospital and patients treated at home require close supervision (Nazer et al 2006, Thornton et al 2004).

For the newly diagnosed or newly referred patient, home visits by members of the specialist team (usually the clinical nurse specialist) provide an opportunity for advice, education and support for the patient and family, as necessary. Domiciliary physiotherapy services are sometimes available and can provide the opportunity for discussion and demonstration of physiotherapy techniques in the home, an opportunity for a more effective assessment of the necessity and appropriateness of equipment and the possibility of specialist physiotherapy during terminal care. There is also evidence of improved adherence with treatment and a reduction in the stress of coping with the disease (Rogers & Goodchild 1996).

The future

Cystic fibrosis is a complex disease. An enormous amount of effort is being expended to improve standards of care (de Boeck 2000), provide guidelines for antibiotic treatment (Cystic Fibrosis Trust 2002a, Doring et al 2000) and evidence, based upon controlled trials, for different aspects of treatment (Cheng et al 2000). More patients (but not enough) are being transplanted and survival figures are improving with greater experience (Vizza et al 2000). The physicians and scientists are continuously evaluating current care (Davis et al 1996) and searching for new therapies to improve quality of life and long-term survival (Rubin 1998).

Gene therapy aims to correct the basic defect by inserting the appropriate DNA or RNA to compensate for the defective gene. The gene is transferred via a ‘carrier’ or vector. To date both viral and non-viral vectors have been extensively investigated but difficulties have been experienced with both. Viral vectors such as the adenovirus can stimulate an inflammatory response and non-viral vectors such as liposomes are not as efficient (Du Bois 1995). Theoretically the transfer of sufficient normal copies of the CFTR gene, to sufficient numbers of affected cells, should result in the production of enough normal protein to reduce the clinical manifestations of cystic fibrosis (Stern & Geddes 1994). Despite several in-vitro and in-vivo studies it has been difficult to convert this theory into practice. Significant advances have, however, been made and there is considerable research in progress which may lead to effective gene therapy in the future (Boyd 2006).

Stem cell therapy aims to permanently correct the genetic defect by developing a cell line that continually produces cells to re-establish a normal epithelium. To date research in stem cell therapy for CF is in its infancy and little is known about the stem cell biology of the lung. Stem cell research is attracting interest and is a hope for future treatment (Boyd 2006).

Physiotherapy management

Advances in the medical management of cystic fibrosis have increased the expectation of survival into the fifth decade of life (Dodge et al 2007). As the science of the basic defect is translated into a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease and novel complications of an ageing population emerge, the physiotherapist’s role is continually challenged. The management encompasses the treatment from birth through childhood and adolescence into adulthood and parenting. It is adapted through changing lifestyles, disease severity and the changes of the acute exacerbation and stable state of the disease. Physiotherapy requires detailed accurate assessment and treatment, tailored to the individual as lifestyle and disease severity change. In parallel with the advances in the medical management, the role of the physiotherapist has expanded from the clearance of bronchial secretions to include the assessment of exercise capacity and the prescription of safe and effective exercise programmes, assessment and education of inhalation therapy and in the later stages of the disease the use of oxygen therapy and non-invasive ventilation (NIV).

Infants and small children

In the past few years, the approach to airway clearance in babies with CF has changed considerably. Many other airway clearance techniques have been developed (Chapter 5) and some of these, such as positive expiratory pressure (PEP) applied via a facemask, assisted autogenic drainage (AD) and physical activity are now used in the infant/paediatric population. Many centres throughout the world have modified the traditional approach by omitting the use of gravity-assisted positioning in the drainage regimen. This has been to a large extent due to growing clinical concerns regarding gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gravitational effects in the tipped position theoretically lead to a lowering of intra-abdominal pressure and an increase in intrathoracic pressure. This, together with the increase in diaphragmatic activity, may enhance the competence of the oesophageal sphincter (Sindel et al 1989). Despite this theoretical assumption, infants with CF are known to have a higher incidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) and studies have suggested that this is exacerbated by use of the head-down tipped position during airway clearance (Button et al 1997). Other groups have not reproduced these findings, albeit in slightly differing cohorts (Phillips 1996, Taylor & Threlfall 1997). Longer-term follow-up data from the subjects included in the study by Button et al (1997) suggest that GOR may result in both short- and long-term sequelae in terms of respiratory status (Button et al 2003, 2004). These results have led many centres to discontinue using the head-down tipped position. This remains a slightly contentious issue, and there are centres that continue to use gravity-assisted positioning judiciously. When GOR is suspected, it should be investigated rigorously and if confirmed the airway clearance regimen may need to be modified and anti-reflux medication should be started.

Early diagnosis of CF, particularly since the introduction of neonatal screening in many parts of the world, along with early and aggressive multidisciplinary care, has led to a novel cohort of infants who are apparently free of any respiratory symptoms and are nutritionally healthy. The appropriateness of implementing a routine daily airway clearance regimen in this cohort of infants has raised much debate. Unfortunately there are no studies that have evaluated whether the routine instigation of airway clearance regardless of clinical status is beneficial. The debate continues widely on the international stage and opinion remains divided (Prasad & Main 2006).

Arguments for routine treatment are threefold. First, many feel it is essential to establish a daily routine in order to ensure adherence to therapy in the long term. Secondly, the anatomical and physiological differences in the infant respiratory system (Chapter 10) may make them more vulnerable to chest complications. Finally, there is conclusive evidence that pathophysiological changes in the lungs occur very early, before the onset of clinical signs, with evidence of early inflammation and infection (Armstrong et al 1995), altered respiratory function (Ranganathan et al 2001) and structural changes radiologically (Martinez et al 2005).

However, while the evidence that pathophysiological changes occur early in the disease process is compelling, the early picture is usually not one associated with copious secretions. The value of a daily airway clearance regimen is therefore unclear (Bush & Gotz 2006). In addition there is no doubt that a significant burden of care is imposed on families by routine treatment regimens.

There is little robust evidence with respect to best physiotherapy practice in this group of infants (Button 1999, Constantini et al 2001). The few existing studies that attempt to evaluate the efficacy of airway clearance or to compare the various airway clearance modalities have been undertaken in older populations with established disease (Desmond et al 1983), as have the majority of studies comparing the efficacy of the various techniques (Elkins et al 2006b, Main et al 2005). It is unlikely to be appropriate to extrapolate findings from these studies to a healthy infant who shows no overt signs of respiratory involvement. In the United Kingdom the proposal of a national neonatal screening programme provided a unique opportunity to undertake a randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of routine daily chest physiotherapy in screened infants with CF. Unfortunately this trial did not come to fruition but in attempting to address this important issue, the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Cystic Fibrosis (United Kingdom) undertook a consensus exercise based on the Delphi process (Jones & Hunter 1995) in order to provide expert opinion and guidance for the future care of these infants (Prasad et al 2008). The results of the Delphi process have resulted in guidelines which state that physiotherapists are not required to initiate routine airway clearance if, following careful assessment, the child is well and felt not to have symptoms which would respond to respiratory physiotherapy. It is important to stress that all parents and carers should be taught an appropriate airway clearance regimen, and this is practised and revised to maintain competency. Airway clearance is instigated whenever there are respiratory symptoms and an assessment tool is being developed to assist parents with assessment (Fergusson, personal communication 2007). The Delphi process has also recognized that the more recently developed airway clearance modalities may be more appropriate for these infants, rather than traditional postural drainage or modified postural drainage and percussion, and that physical activity should be greatly emphasized from the outset. The suggestion is not that treatment should be withdrawn, but that a different emphasis be placed on the management to include physical activity and a more flexible and holistic approach supported by an easily accessible specialist physiotherapy service.

Even at a young age treatment should be fun. The young child can be bounced up and down on the parent’s knees, exercises such as ‘wheelbarrows’, jumping on a mini-trampoline (Fig. 18.2A) or the use of a gym ball (Fig 18.2B). Laughing often also stimulates coughing. From the age of 2 years the child can be encouraged to actively participate in breathing techniques in the form of play and other airway clearance modalities (Chapter 5) can be introduced as the child grows. PEP can be made more enjoyable if administrated in the form of bubble PEP (Chapter 5). From as early an age as possible children should be encouraged to play a more active role in their treatment. With increased cooperation, the child can be introduced to various airway clearance techniques and become independent with treatment (Box 18.1).

Box 18.1 Airway clearance techniques

Active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT)

Modified autogenic drainage (M AD)

High-frequency chest wall oscillation (HFCWO)

Intrapulmonary percussive ventilation (IPV)

Oscillating positive expiratory pressure:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree