Bronchiectasis

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a chronic condition with irreversible dilatation and destruction of bronchi commonly diagnosed by high resolution CT scan of the chest. Before the establishment of this technique the diagnosis was made by bronchogram. This section on bronchiectasis, with illustrative radiology, microbiology, and pathology, discusses the investigation, diagnosis, and management of bronchiectasis. In addition, the investigation, diagnosis, and management of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and cystic fibrosis are covered in this section.

Aetiology

The initial bronchial damage which leads to bronchiectasis is often caused by childhood infections such as whooping cough or measles. Severe lung infections in adults, such as Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, aspiration pneumonia, or TB may also result in bronchiectasis.

Other conditions associated with bronchiectasis include:

Infective, e.g. post whooping cough, pneumonia, or TB.

Inflammatory, e.g. Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Immunodeficiency, e.g. common variable immunodeficiency and HIV infection.

Mucociliary defects such as cystic fibrosis, Kartagener’s syndrome, primary ciliary dyskinesia, and Young’s syndrome.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Bronchial obstruction and bronchopulmonary sequestration.

Congenital cartilage deficiency and tracheobronchomegaly.

Yellow nail syndrome.

Unilateral hyperlucent lung.

Patients with established bronchiectasis are commonly chronically colonized with upper respiratory tract organisms.

Pathogens which cause recurrent purulent infections include Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, coliforms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, anaerobic cocci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In cystic bronchiectasis, mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa may establish persistent colonization.

The distribution of the bronchiectasis may give an idea of aetiology. Upper lobe bronchiectasis can be seen typically post-TB and in patients with cystic fibrosis, while proximal bronchiectasis is seen with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Localized bronchiectasis can be seen distal to a foreign body.

Presentation

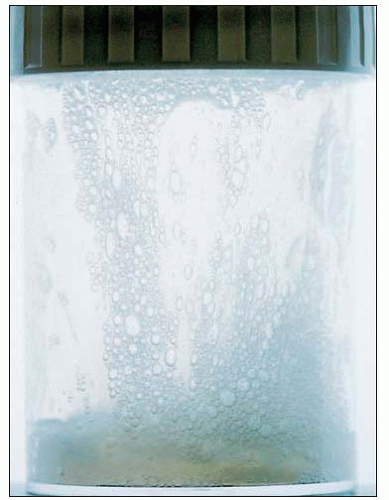

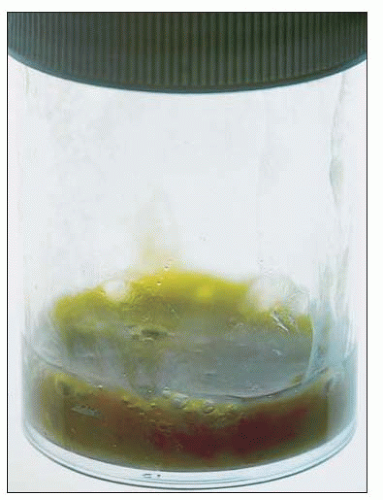

Patients usually present with recurrent chest infections, but the presentation is variable depending on the severity of the bronchiectasis. Between exacerbations, patients with mild bronchiectasis (tubular bronchiectasis) may have no sputum production or small volumes (<5 ml) of mucoid or light mucopurulent phlegm (6.1). With more advanced bronchiectasis (varicose and cystic bronchiectasis, cystic bronchiectasis being the most severe), between exacerbations patients usually expectorate mucopurulent or frankly purulent sputum on a daily basis even when apparently clinically stable (6.2). In patients with advanced cystic bronchiectasis, the sputum volume can be >50 ml/24 h. Patients with more advanced bronchiectasis usually suffer the greatest frequency of chest infections.

6.1 Sputum sample from a patient with mild tubular bronchiectasis predominantly expectorating mucoid sputum (clear/grey) when clinically stable. |

6.2 Sputum sample from a patient with advanced cystic bronchiectasis expectorating purulent sputum (dark yellow or green) even when clinically stable. |

Investigations

Radiology

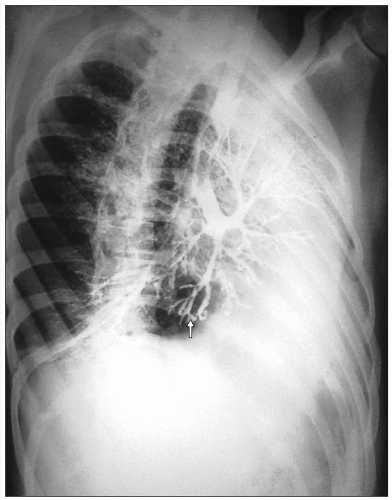

Before the establishment of CT scanning the gold standard for diagnosing bronchiectasis was a bronchogram.

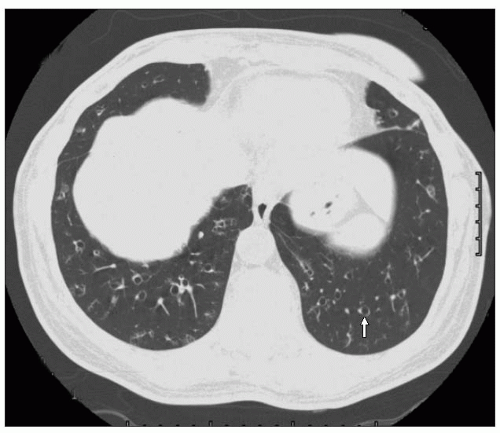

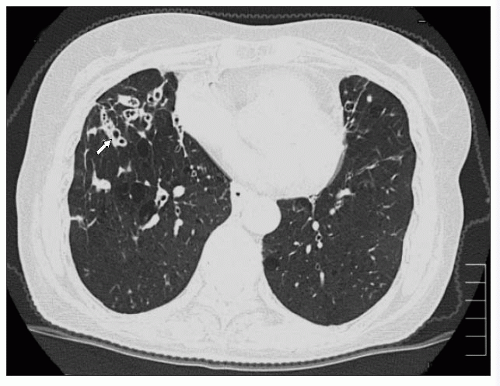

6.4 Chest CT scan from a patient with tubular bronchiectasis, in which the bronchus is larger than the adjacent vessel in both lower lobes, the ‘signet ring’ sign (one example is arrowed). |

6.5 Chest CT scan from a patient with tubular bronchiectasis, in which the bronchus has a thick wall and is larger than the adjacent vessel, in particular affecting the right middle lobe (one example is arrowed). |

Illustrative cases

The bronchogram revealed bronchial dilatation in the left lower lobe in keeping with bronchiectasis (6.3). Figures 6.4, 6.5 are CT chest scans (lung window setting) showing tubular bronchiectasis. In 6.4, the bronchus is larger than the adjacent vessel in both lower lobes, the ‘signet ring’ sign. In

6.5 the scan reveals tubular bronchiectasis in which the bronchus has a thick wall and is larger than the adjacent vessel, in particular affecting the right middle lobe.

6.5 the scan reveals tubular bronchiectasis in which the bronchus has a thick wall and is larger than the adjacent vessel, in particular affecting the right middle lobe.

The degree of bronchiectasis is variable from mild bronchiectasis (tubular bronchiectasis), in which the bronchus is dilated and thickened compared to the adjacent vessel, to patients having varicose bronchiectasis, in which the bronchus is irregular and nontapering, to patients with advanced cystic bronchiectasis. Often the chest radiograph is normal in patients with tubular bronchiectasis and the condition is only diagnosed from a high resolution CT chest scan. A chest radiograph of a patient with cystic bronchiectasis is shown (6.6). Note in this case the large thin-walled cysts that often contain mucus. Common findings on a chest radiograph with advanced bronchiectasis include tramline shadows, cystic lesions that can be fluid filled, and volume loss with fibrotic scarring. Cystic lesions are demonstrated in 6.7 in a CT scan from a patient with cystic bronchiectasis. Macroscopic picture of lung tissue with cystic bronchiectasis is shown in 6.8. The lung contains numerous thin-walled cysts which represent damaged and cystically dilated airways.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree