Bifurcation Lesions—The Role of Stents

Antonio Colombo

Goran Stankovic

Bernhard Reimers

The introduction of drug-eluting stents (DES) is changing the way we treat bifurcation lesions. A few initial considerations are necessary.

Because bifurcation lesions can have many unique presentations, it is almost futile to compare different studies. Attempts to classify bifurcation lesions (1, 2, 3, 4) are commendable, but suffer from the limitations of coronary angiography (e.g., different plaque distribution and extent of disease when evaluated by intravascular ultrasound [IVUS]) (5). The lesion itself—especially its plaque characteristics—acquires, in the context of a bifurcation, a unique character. For example, a soft plaque distributed toward the origin of the sidebranch is more prone to shift, upon main branch dilatation, toward the side-branch than is a fibrous plaque. Some complicating factors are unrecognizable at the time of angiography and, therefore, cannot be quantified. This lack of ability to quantify a number of important factors makes the entire field of bifurcation lesion treatment open to more interpretation and increases the difficulties that arise in evaluating and comparing study results. This lack of information introduces several very important unanswered questions:

How will the side-branch behave following main-branch stenting?

Will this behavior be influenced by the presence of disease at the origin and inside the side-branch?

How will the plaque composition in the main and sidebranch affect the final result and influence the immediate and long-term results following a specific approach?

Is the angle between the main and the side-branch important in affecting the fluid dynamics of immediate results, and will it act on the long-term results?

Nothing more needs to be added to support the concept that bifurcation lesions are, by their constitution, a tremendously variable entity. In this subset of lesions, we observe a unique “lesion to lesion interaction”: The two branches affect each other. In addition, the therapeutic strategy adopted on one branch will affect the other branch.

All these considerations are important in giving us an overview of both the field itself and of the knowledge we must acquire to plan studies that attempt to evaluate the behavior of all possible important variables related to bifurcation lesions.

THE STUDIES AVAILABLE

The sirolimus-eluting stent bifurcation study has given us some important initial direction to structure our approach for the treatment of bifurcation lesions (6). The most important findings of this study are:

Compared to historical studies utilizing bare metal stents (BMS) (1,7, 8, 9, 10) a remarkable improvement has been achieved in the treatment of bifurcation lesions when one (main branch) or two stents (main branch and side-branch) are implanted.

The side-branch seems the weak link in the chain, in terms of a higher risk of angiographic restenosis (still around 20%) and a slightly higher risk of thrombosis.

When possible, the placement of a single stent in the main branch gives a similar result of placement of two stents.

Suboptimal coverage with struts and drugs at the ostium of the side-branch is a possible contributing factor to side-branch restenosis.

In addition to this study, a number of reports (at this time, still personal communications or in the context of presentations on the topic of bifurcation lesions) stress the issue of possible stent recoil at the ostium of the side-branch.

These initial data should help us redefine the approach to bifurcation lesions in the era of DES.

ONE VERSUS TWO STENTS; STENTING SIDE-BRANCHES

Two important questions arise in the planned treatment of bifurcation lesions: should the operator implant one or two stents?, and is it necessary to stent side-branches? Many answers exist, all depending on certain variables.

The Size and Territory of Distribution of the Side-Branch

The concept of side-branch must be clearly defined. As intuitive as the meaning of the term “side-branch” may be, a misleading connotation is attached to it. The term “sidebranch” may imply a vessel of less importance when compared to the main branch. Although this may be true in many cases, a number of situations arise in which the sidebranch is as important as the main branch, in regards to size and territory of distribution. A left main artery with its left anterior descending (LAD) and circumflex (LCX); the presence of a large intermediate branch; a large, long diagonal branch; a right coronary artery that bifurcates into a posterior descending artery and a number of posterolateral branches; a dominant circumflex that bifurcates into a distal circumflex and a large obtuse marginal branch all are examples in which the side-branch is equally important to the main branch. These situations are quite different from the standard concept of the smaller diagonal branch that commonly is used to define a side-branch.

Therefore, to correctly determine the course of treatment, we must ask a further question:

Are we dealing with a bifurcation giving origin to a sidebranch from the main branch or are we evaluating an anatomic situation in which two branches exist (a condition in which the term “side-branch” may not be so appropriate)?

The more the side-branch is functionally and anatomically similar to the main branch, the more likely it is that two stents will be required.

If the side-branch really is a side-branch, this will encourage an approach using one stent in the main branch and a balloon angioplasty (BA) in the side-branch. The other condition will make us more likely to use two stents.

Other factors then come into play.

Angle between the Main and Side-Branch and Amount of Disease at Side-Branch Ostium

Two more elements that must be to be taken into account are the angle between the main and side-branch, and the presence of disease (plaque) at the origin of the side-branch.

The angle of origin of the branch (the side-branch in most cases) can be an acute angle, a right angle, or an obtuse angle. This angle influences how the side-branch ostium will react upon the positioning of a stent on the main branch. The more acute the angle between the two branches, the more likely it is that we will observe a narrowing at the ostium of the side-branch following stenting of the main branch.

Another element to consider when looking at the angle between the two branches is the difficulty of recrossing into the side-branch following the stenting of the main branch.

The relationship between angle of branch origin and plaque shift also must be considered. An acute angle causes more plaque shift or compromise of the ostium of the side-branch, but it should facilitate recrossing with a wire into the side-branch. Conversely, an obtuse angle will be less likely to be associated with plaque shift, but it will make wire recrossing more difficult.

The more acute the angle between the two branches, the more likely it is that two stents will be required.

The more difficult we assume it will be to recross into the side-branch, the more likely it is that two stents will be used.

The amount of plaque or degree of stenosis at the origin of the side-branch is also very important in our decision process. This variable is best evaluated by knowing the type of atherosclerotic plaque involved, both in the main vessel and in the side-branch, and its distribution. Unfortunately, angiography gives only a limited insight into these data, and IVUS cannot be proposed in the routine evaluation of bifurcations. The type of the plaque at the origin of the side-branch and its amount should be taken into account when choosing whether to predilate and how to dilate the side-branch. Before deciding to place one or two stents, a fibrotic side-branch, if properly predilated with a cutting balloon, may not need a stent after the main branch is stented. Thus, the extent of initial improvement in the side-branch achieved with dilatation, as well as the degree of stenosis at the origin of the side-branch, must be considered. As well, it is important to take into account how flow in the side-branch may have deteriorated following dilatation of the main branch. The results achieved through dilatation affect the ultimate treatment decision.

The more severe the stenosis at the ostium of the side-branch, the more likely it is that two stents will be required.

The less improvement obtained (sometimes a dissection) on side-branch dilatation, the more likely it is that two stents will be required.

The more deterioration at the ostium of the side-branch, the more likely it is that two stents will be required.

THE FINAL DECISION

The decision to use one, two, or sometimes even three stents (in the case of a trifurcation) should be made as early as possible. An appropriate and timely decision affects the result, and helps to save time and lower both the cost and the risk of complications.

It is important to remember that, if the decision is made to use one stent (on the main branch), the possibility almost always exists that a second stent can be placed in the side-branch if the initial result is not optimal or adequate. And, although this “provisional stenting” (11,12) allows the operator to defer the decision to use multiple stents in most cases after having stented the main branch and performed a balloon dilatation of the side-branch and a kissing balloon dilatation of both branches, it does not allow the further performance of some techniques, such as V stenting, and it may make recrossing with a stent into the side-branch a difficult, if not impossible, task.

All these considerations must be taken into account when making the initial decision regarding the implantation of two stents or of one stent with provisional sidebranch stenting.

SIDE-BRANCH PRESERVATION

With few exceptions, most side-branches of a bifurcation lesion must maintain patency during and after the procedure. However, this does not mean that each side-branch must be treated with balloon inflation or stenting.

Occasionally, some small side-branches (usually 1.5 mm or smaller in diameter) do not need treatment or protection, typically in the context of a trifurcation or a second subdivision of a diagonal branch and especially when diffusely diseased and having a small distribution area. Their closure can be accepted to minimize the complexity of the procedure.

The strategy to protect a minor side-branch is to place a wire that can remain in place until the stenting procedure on the main branch has been completed. These temporary “jailed” wires can be retrieved without difficulty.

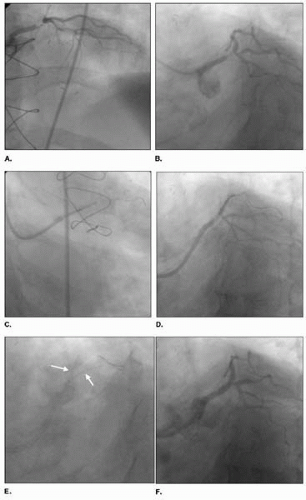

IMPOSSIBLE SIDE-BRANCH ACCESS

Although rare, some circumstances arise in which, due to the location of the plaque in the main branch and angulation of the side-branch, a guidewire cannot be advanced into the side-branch. After having attempted different types of wires with all sorts of curves (and exhausting all personal tricks), the operator may be left with the impossibility of advancing a wire into the side-branch. As rare as this condition may be, it does occur. At this point, a few options are available: (a) abort the procedure, because the risk of losing the side-branch may be too high considering the size and distribution of the branch (typically an angulated circumflex artery); (b) perform a directional atherectomy on the main branch, with the intent of removing the plaque that is preventing entry toward the side-branch (Fig. 29.1); or (c) underdilate the main branch using a balloon, upon the rationale that the plaque modification and hopefully a favorable plaque shift will facilitate access toward the side-branch.

Each of these three options has its rationale, and the specific anatomic condition and clinical scenario may direct the operator to choose one versus the other.

ROLE OF ATHERECTOMY DEBULKING

Directional coronary atherectomy has been considered ideal for bifurcation lesions. The rationale for plaque removal in this setting is extensive, and a number of positive anecdotal experiences have been documented (13, 14, 15, 16). The Stenting after Optimal Lesion Debulking (SOLD) registry (17) included bifurcation lesions, and the results were very encouraging. These same results launched the Atherectomy before Multi-Link Improves Lumen Gain and Clinical Outcomes (AMIGO) trial. Unfortunately, this study failed to support the original findings of the SOLD registry, even in the subgroup of lesions involving a bifurcation (18). A primary problem of directional atherectomy, and one which also may have affected the results of the AMIGO trial, is that the technique is very operator dependent and the amount of tissue removal varies considerably, depending on the commitment to perform extensive debulking. In addition, except for the very recent introduction of the Silver Hawk device (Fox Hollow Technologies, Redwood City, California), no further development in atherectomy devices has occurred recently.

Recently, the COMBAT study utilizing the Silver Hawk device has been launched in the United States. Whatever the results, we suspect that the competition from the introduction of DES will narrow significantly the areas of application for atherectomy.

Despite these concerns, and despite the lack of strong scientific evidence in support of plaque debulking in bifurcation lesions, our experience in this setting has been favorable, and we still occasionally combine atherectomy and DES when the anatomic setting is appropriate, such as in a left main stenosis with a large plaque burden demonstrated by IVUS.

ROLE OF ROTABLATION

Rotational atherectomy is a procedure that, in the last few years, has been used less and less frequently. In most cardiac catheterization laboratories, this procedure is used in less than 5% of all interventions, or not at all. Early reports stated an advantage in facilitating stent delivery and expansion, with a suggestion for clinical benefit when employed in lesions that were amenable to rotablation debulking technology (19). The SPORT randomized study utilizing rotational atherectomy and stenting failed to support any advantage to this technology over standard stenting. Our interpretation is that a niche technology cannot demonstrate its advantage when used outside the area where it should work at its best. Unfortunately, due to the randomized design of the SPORT trial, heavily calcified lesions were not included.

All these considerations make us suggest that rotational atherectomy most probably is beneficial and sometimes essential in heavily calcified bifurcation lesions. In most cases, rotablation is performed only on the main branch, but occasionally (very rarely) also on the side-branch, or only the side-branch is treated (only one wire is left in place). We believe that, especially with use of DES, this lesion preparation, resulting in the compliance change of a very calcified lesion, can substantially facilitate stent delivery and symmetrical stent expansion with more homogeneous drug delivery (19, 20, 21).

ROLE OF CUTTING BALLOON

A number of single-center studies reported the beneficial combination of stenting preceded by cutting balloon dilatation (22, 23, 24, 25). Bifurcation lesions in which a large, and frequently fibrotic, plaque mass exists in the ostium of the side-branch seem an ideal setting for this device (26). The Restenosis Reduction by Cutting Balloon Evaluation (REDUCE III) trial evaluated the role of cutting balloon dilatation before stenting versus standard balloon dilatation in a variety of lesions (27). This trial reported a lower restenosis rate (11.8% versus 18.8%, p = 0.04) when lesions were predilated using the cutting balloon. The fact that the final lumen diameter postprocedure was larger in the cutting balloon arm, and that the late loss was .74 mm for both strategies, suggests that the main advantage was toward better stent expansion.

So, what is the take-home message? As for rotational atherectomy, it is difficult to demonstrate that a niche device has an advantage in every lesion. For this reason, we suggest the use of a cutting balloon in moderately calcific and in fibrotic lesions, especially those that involve the origin of the side-branch. In heavily calcified lesions, the cutting balloon could be the second step following small-burr rotablation. This strategy minimizes distal embolization and maximizes lumen, thanks to the access achieved by large-size cutting balloons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree