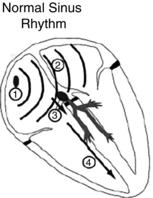

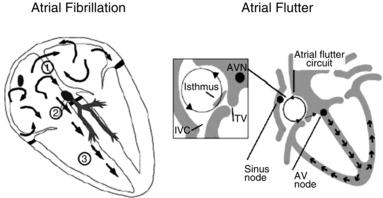

Figure 20.1 Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter pathogenesis.(Source:Waktare J. Circulation 2002; 106:14–16 and Boyer M, Koplan BA. Circulation 2005; 112:e334–336. Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health).

20.3 ETIOLOGY

The most common predisposing factor for the development of atrial fibrillation is structural heart disease. Mitral valvular regurgitation, congenital heart disease, heart failure/cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and diastolic dysfunction can all lead to atrial fibrillation by causing increased atrial pressure or atrial stretch. This, in turn, leads to left atrial enlargement. Atrial fibrillation can also occur secondary to other disease processes that cause generalized inflammation of the myocardium, such as hyperthyroidism, sepsis, and myocarditis. Other risk factors for the development of atrial fibrillation include obesity, metabolic syndrome, older age, obstructive sleep apnea and other cardiopulmonary disease such as pulmonary embolus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In addition, atrial fibrillation is a common arrhythmia after cardiac surgery due to the resultant hyperinflammatory state. Atrial fibrillation can occur in the absence of structural heart disease, in which case it is referred to as “lone” atrial fibrillation. This typically occurs in younger males and it carries a favorable prognosis.

Atrial flutter can be divided into typical or atypical atrial flutter. Typical atrial flutter occurs in the right atrium; it moves in a counterclockwise direction and involves a tract that passes through the cavo-triscuspid isthmus. While it shares some of the etiologic factors with atrial fibrillation, it is frequently idiopathic. In contrast, atypical atrial flutter is either a right atrial flutter that moves in a clockwise direction or a left-sided atrial flutter. Left atrial flutters are most common after a previous left atrial radiofrequency ablation procedure, MAZE procedure, or previous mitral valve surgery. In this situation, the myocardial scars from previous ablations or surgical suture lines create an anatomical substrate around which the flutter can move in a circular fashion.

20.4 CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The initial clinical presentations of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter can range from asymptomatic to markedly symptomatic. To a large degree, whether or not a patient is symptomatic depends upon the ventricular rate associated with the atrial arrhythmia. Patients with a rapid ventricular response (>100 beats per minute) will often complain of dyspnea, exercise intolerance, fatigue and the sensation of rapid palpitations. If the rapid ventricular response has been present for a prolonged period of time, the patient may develop a tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy and their initial presentation may mimic that of newly-diagnosed congestive heart failure. However, many patients with atrial fibrillation are often asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic at diagnosis. These patients’ only complaint may be that of generalized fatigue which they may have attributed to some other cause. Approximately 50% of patients with atrial fibrillation state that they are asymptomatic; however, a large percentage of the population relay an increase in functional capacity post cardioversion when in normal rhythm. Thus, many patients do not realize that atrial fibrillation limits their functionality until they are in a normal rhythm.

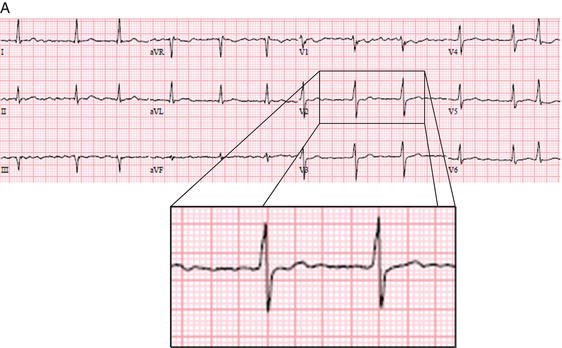

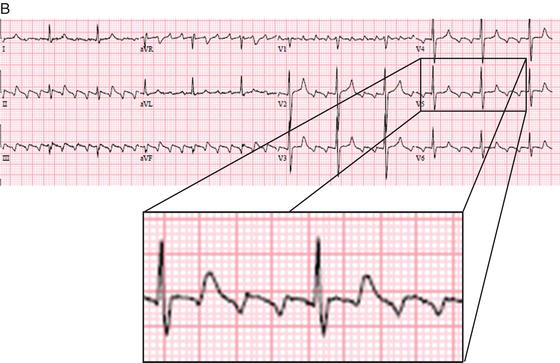

Figure 20.2 A Electrocardiogram of atrial fibrillation. B Electrocardiogram of typical atrial flutter. Note the regular uniform P waves.

Upon physical examination, patients with atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter are often noted to have a rapid and irregular pulse. Cardiac auscultation is classically notable for an “irregularly irregular” heartbeat. Atrial flutter can have a regular or a “regularly irregular” heartbeat. An electrocardiogram confirms the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (Figure 20.2). Atrial fibrillation is characterized by a lack of evidence of organized atrial activity. There are no clear p waves seen on the ECG. The ventricular response is variable and irregular due to the chaotic nature of atrial depolarizations. In contrast, atrial flutter has a “sawtooth” pattern of the atrial flutter waves that range from 250–350 beats per minute. The ventricular response typically occurs in a pattern of 2:1 or 3:1 conduction from the flutter waves. As compared to atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation appears more disorganized on the electrocardiogram.

20.5 EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The initial evaluation of a patient with atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation should proceed in a systematic fashion. The first step is to assess the patient and determine whether or not he/she is hemodynamically stable or unstable. A patient with atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation that has associated hypotension, angina or evidence of ongoing myocardial ischemia, dyspnea or other symptoms of decompensated heart failure is considered to be unstable and treatment should be geared towards restoring sinus rhythm via cardioversion. Most commonly, this is accomplished by giving the patient intravenous sedation and then performing a synchronized DC cardioversion. In these patients, the risk of a potential thromboembolic event is outweighed by the immediate risk posed by the unstable nature of the arrhythmia.

If the patient is hemodynamically stable, or once sinus rhythm is achieved through cardioversion, then a search for etiologic factors is the next logical step. A detailed history should focus on elucidating symptoms of heart failure, hyperthyroidism, and sleep apnea as these are all conditions associated with the development of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. Since anticoagulation will also be part of the initial management of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation, it is important to assess for any historical elements that may indicate a contraindication to anticoagulation, such as recent stroke, intracranial mass, major surgical procedure, or gastrointestinal bleed requiring blood transfusion. With elderly patients, an assessment of their fall risk and consequent risk for intracranial bleed if anticoagulated should also be taken into consideration. For patients with suspected atrial flutter, additional historical elements that should be considered are a previous history of atrial ablation procedure and/or cardiac surgery.

In terms of diagnostic studies, the initial test should be a 12-lead electrocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis of atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation. Initial laboratory investigations should include serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level, a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and a coagulation profile (PT, PTT and INR) to establish a baseline for initiation of anticoagulation. An echocardiogram should also be performed to evaluate for the presence of structural heart disease. This is important for both an etiologic as well as prognostic evaluation. A patient with a cardiomyopathy or valvular heart disease has a higher incidence of secondary atrial arrhythmias than patients without these structural abnormalities. Treatment should also address the underlying cause for the cardiomyopathy or valvular heart disease in addition to treatment of the arrhythmia itself. If patients have a newly-discovered non-ischemic cardiomyopathy that cannot be attributed to any other condition (e.g. infiltrative disease, viral infection, familial dilated cardiomyopathy, etc.) then consideration should be given for a tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy that may be the result of a prolonged period of uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. For these patients, maintenance of sinus rhythm and/or aggressive rate control will be of paramount importance. Atrial fibrillation also carries a more ominous prognosis for patients with a previous history of stroke/transient ischemic attack or congestive heart failure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree