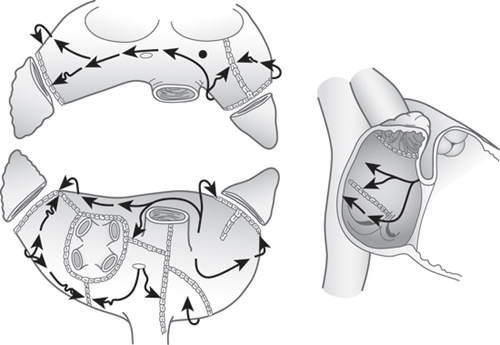

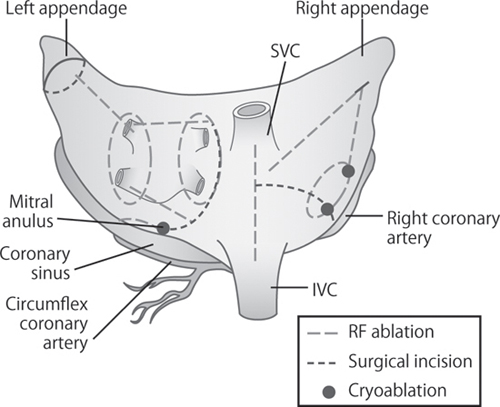

CHAPTER 9 Christopher P. Lawrance, MD, and Ralph J. Damiano, Jr., MD Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, present in approximately 2% of the general population and 10% of individuals over the age of 80.1–5 The treatment of AF results in a significant financial burden, with an estimated annual cost of $8705 per patient, and a total annual cost of over $6 billion in the United States alone.6 AF is associated with significant morbidity and mortality related to its three detrimental sequelae, which include: (1) palpitations, which cause patient discomfort and anxiety; (2) loss of synchronous atrioventricular (AV) contraction, compromising cardiac hemodynamics, resulting in ventricular dysfunction; and (3) stasis of blood flow in the left atrium (LA), which can result in thromboembolism and stroke.7–11 An understanding of these sequelae has been important in the development of surgical procedures to treat medically refractory AF. Because of the poor efficacy of medical therapy for AF, several surgical procedures were developed in the 1980s, which led to the introduction of the current gold-standard surgical treatment for AF, the Cox-Maze (CM) procedure. In 1980, Dr. James Cox developed the left atrial isolation procedure, which attempted to confine AF to the LA.12 By taking advantage of the fact that the sinoatrial (SA) node, AV node, and internodal pathways are located in the right atrium (RA) and intra-atrial septum, the procedure allowed for restoration of normal sinus rhythm (SR) after electrically isolating the LA from the rest of the heart. This procedure was beneficial in that it corrected 2 of the 3 sequelae of AF. By resuming normal SR between the RA and ventricle, right-sided synchrony was reestablished, resulting in an improvement in right-sided cardiac output and improved hemodynamics. However, because the electrically isolated LA remained in AF, the procedure did not address the risk of thromboembolism. The procedure also did not address patients in whom AF originated outside of the LA. Scheinman et al.13 described catheter ablation of the His bundle, which was successful in electrically isolating the atria from the ventricles. While allowing for rate control, this procedure necessitated the need for a permanent pacemaker to restore normal ventricular rhythm. The procedure also allowed both atria to remain in AF, thereby causing dyssynchrony between the contractions of the atria and ventricles, and did not address the risk of thromboembolism. Despite these limitations, this procedure is still used in symptomatic patients who are refractory to medical therapy and are poor candidates for curative but more invasive procedures. Sharma et al.14 introduced the corridor procedure for the treatment of AF. This operation involved isolating a strip of atrial septum that contained both the SA node and AV node from surrounding atrial tissue. This allowed the SA node alone to drive ventricular contraction, correcting the irregular heart rhythm. This procedure, however, allowed most of the atria to remain in AF and did not address either the AV dyssynchrony or the risk of thromboembolism. The first clinically successful surgical procedure for the treatment of AF was introduced in 1987 by Dr. James L. Cox at Washington University in St. Louis, MO after nearly a decade of basic research.15–17 This procedure, the Cox-Maze procedure, was designed to interrupt the macro-reentrant circuits that were thought to be responsible for AF, thereby making it impossible for the atrium to maintain AF or atrial flutter. Compared with previous attempts at surgically correcting AF, the Cox-Maze procedure preserved SR and maintained AV synchrony, thus decreasing the risk of thromboembolism and stroke. The operation involved creating multiple incisions across both the left and right atria in a way such that the SA node could still activate most of the atrial tissue and thus preserve atrial contraction. Shortly after the clinical implementation of the Cox-Maze procedure, the procedure was modified because of late chronotropic incompetence in many patients which required pacemaker implantation. The new modification was coined the Cox-Maze II. Unfortunately, this lesion set proved to be technically difficult to perform, so it was again modified to the Cox-Maze III (Figure 9.1). The Cox-Maze III was widely adopted in the 1990s and became the gold standard for the surgical treatment of AF owing to its ability to restore sinus rhythm in over 90% of patients with symptomatic AF.18 Cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III lesion set. Source: Adapted from Cox JL, Boineau JP, Schuessler RB, et al. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;110:473–484. Although results using the Cox-Maze III were excellent, the operation was limited in its use because of its technical difficulty. Few surgeons were willing to add the procedure to concomitant operations because of the associated long cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times. As a result, <1% of patients with AF receiving cardiac surgery also received a Cox-Maze III operation.19 Advances in ablation technology have revolutionized the surgical treatment of AF over the last 15 years. Experimental studies using bipolar radiofrequency (RF) clamps showed that linear lines of ablation could effectively reproduce the traditional “cut-and-sew” technique.20 This experimental work led to the clinical adoption of bipolar RF ablation and cryoablation to replace most of the incisions of the Cox-Maze III. This new procedure has been termed the Cox-Maze IV (Figure 9.2).21 Clinical case series have revealed that the Cox-Maze IV has equal efficacy and lower CPB times than the Cox-Maze III.22 It was also realized that the use of ablation technology allowed for the development of minimally invasive approaches. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation Cox-Maze IV schematic. The Heart Rhythm Society, in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons created a consensus statement in 2007 to evaluate the indications for both catheter and surgical ablation of AF, which was later revised in 2012.23 The consensus of the task force was that the following were appropriate indications for the surgical ablation of AF: (1) symptomatic or selected asymptomatic AF patients undergoing cardiac surgery in whom the ablation can be performed with minimal risk, and (2) stand-alone AF surgery should be considered for symptomatic AF patients who have failed medical management and either prefer a surgical approach, have failed catheter ablation, or are not candidates for catheter ablation. In our opinion, other patients who should be considered are patients with a CHADS2 score of ≥2 who have developed a contraindication to warfarin, or patients who have had a stroke while being properly anticoagulated. In patients with a CHADS2 score ≥2 referred for a Cox-Maze procedure at our institution, the overall annual risk of a late neurologic event was decreased to 0.2% after the surgery with the majority of patients off all anticoagulation.24 Traditionally, the Cox-Maze IV procedure has been performed through a sternotomy which is described below. However, advances in minimally invasive surgery have allowed the procedure to be performed through a (5–6 cm) right minithoracotomy (RMT) in most patients.25,26 Contraindications to this approach include patients with severe respiratory disease, previous right thoracotomy, or aortoiliac disease. The RMT is performed using single-lung inflation and femoral cannulation for CPB. The lesion set is largely the same between the two approaches with the exceptions described below. Regardless of the approach, all patients have intraoperative transesophageal echocardiograms to evaluate for the presence of left atrial thrombus. Patients in AF at the time of surgery are electrically cardioverted. It should be noted that each RF ablation line is created by performing 2 to 3 ablations with the clamp to ensure transmural ablation. The patient is prepped and draped in the supine position and a median sternotomy is performed. A pericardial cradle is created and central cannulation is performed. While on normothermic CPB, both the right and left pulmonary veins (PVs) are bluntly dissected at their confluences and surrounded with umbilical tape when performed through a sternotomy. The bipolar RF clamp is first passed around the right and then the left PVs, incorporating as generous a cuff of atrial tissue as possible. Typically 2 to 3 ablations are performed around this cuff to ensure a circumferential transmural ablation. When performed through a RMT, only the right PVs are epicardially isolated. The left PVs are endocardially isolated during the creation of the LA lesion set later in the procedure. Exit block is confirmed by documenting failure to pace from each PV when performed through a sternotomy and from the right PVs when performed through a RMT. The RA lesion set can be seen in Figure 9.3. The patient is cooled to 34°C and while the heart is beating, a pursestring is placed at the base of the RA appendage (RAA). Through this pursestring, the jaw of the bipolar RF clamp is inserted into the RA. An ablation line is created along the RA free wall toward the superior vena cava (SVC). A vertical atriotomy is then performed extending from the intra-atrial septum toward the AV groove, near the free margin of the heart. This incision should be at least 2 cm from the previous RA free wall ablation line to avoid creating an area of slow conduction. When performed through a RMT, this incision is replaced by two additional pursestrings (Figure 9.3

Atrial Fibrillation: A Surgical Approach to Improving Patient Outcomes

INTRODUCTION

HISTORY OF SURGICAL ABLATION FOR AF

DEVELOPMENT OF THE COX-MAZE PROCEDURE

PATIENT SELECTION

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Preparation and Pulmonary Vein Isolation

Right Atrial Lesion Set

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree