Chapter 34

Atrial Fibrillation

1. How common is atrial fibrillation (AF)?

2. What cardiovascular diseases are likely to coexist in patients with AF?

3. What arrhythmias are related to AF?

4. What are the main anatomic and physiologic substrates for the initiation of AF?

5. Which agents are effective in slowing the ventricular response in acute AF?

6. How do you decide which antithrombotic therapy is most appropriate?

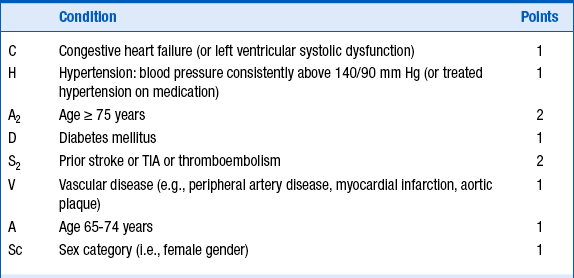

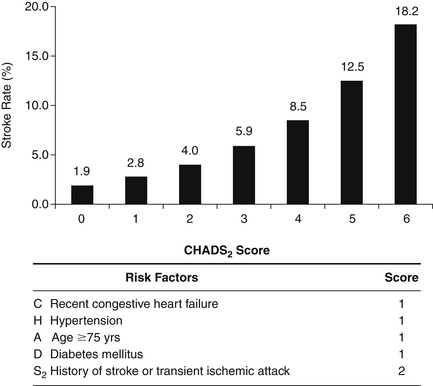

Several schemes for stratification of stroke risk can identify patients who benefit most and least from anticoagulation. The most commonly used tool as outlined in the current guidelines is the CHADS2 score for AF stroke risk scheme (Fig. 34-1), in which patients are stratified for risk according to the presence of moderate risk factors (1 point) and high risk factors (2 points). The use of appropriate anticoagulation is then decided according to the sum of points, as outlined in Table 34-1. A recently updated and modified CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system (Table 34-2) has been validated and used in patients who fall in the intermediate risk category. CHA2DS2-VASc assigns points for risk factors not included in the CHADS2 score, such as female gender, age 65 to 75, and vascular disease.

TABLE 34-1

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY/AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION/EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY 2006 GUIDELINES: RECOMMENDED THERAPIES ACCORDING TO CHADS2 STROKE RISK

| Risk Category | Recommended Therapy |

| No risk factors | Aspirin, 81-325 mg daily |

| One moderate risk factor | Aspirin, 81-325 mg daily, or warfarin (INR 2-3, target 2.5) (depending on patient preference) |

| Any high risk factor or >1 moderate risk factor | Warfarin (INR 2-3, target 2.5) |