Treatment has to be tailored to the individual according to the cause, clinical effects and associated risks from the arrhythmia. Though cardioversion usually restores sinus rhythm, recurrence is common. Flecainide, amiodarone and sotalol but not digoxin may terminate and/or prevent atrial fibrillation. The ventricular response to atrial fibrillation can be controlled by calcium antagonists or beta-blockers: digoxin may fail to control the rate, particularly during exercise.

Stratification of risk of embolism using the CHA2DS2VASc system guides the therapeutic options in non-valvular fibrillation: aspirin, oral anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin or dabigatran), or left atrial occlusion device.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. Indeed, as a result of increased life expectancy in the population, and in particular in patients with heart disease, its incidence is increasing.

It is important to be familiar with the arrhythmia’s various causes and clinical manifestations, and to appreciate that management of the rhythm disturbance has to be tailored to the individual depending on its aetiology, associated risk and symptoms.

ECG characteristics

During atrial fibrillation, the atria discharge at a rate between 350 and 600 beats/min. The arrhythmia is due to multiple wavelets of electrical activity randomly circulating within the atrial myocardium. The very rapid electrical activity results in loss of effective atrial contraction.

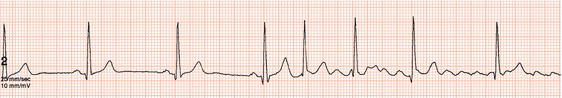

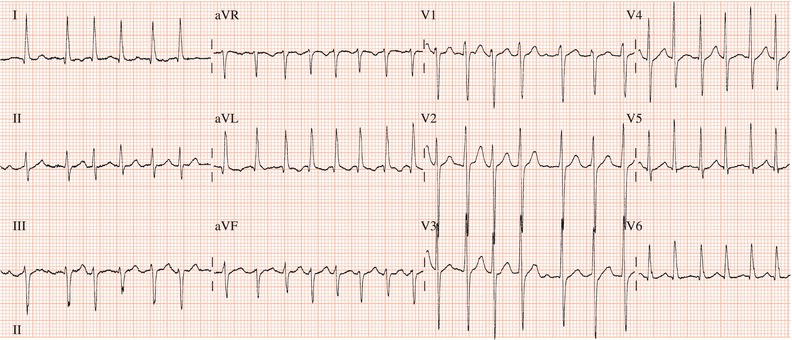

Figure 6.2 Atrial fibrillation: f waves appear coarse in V1, fine in II and are not seen in V5. There is a totally irregular ventricular rhythm.

Atrial activity

The rapid and chaotic atrial activity during atrial fibrillation results in very rapid, small, irregular waves. The amplitude of these f waves varies from patient to patient, and also from ECG lead to lead: in some leads, f waves may not be apparent, whereas in other leads, especially lead V1, the waves may appear so coarse that atrial flutter is suspected, though the atrial activity will be faster than is normally seen in atrial flutter (Figures 6.1, 6.2). Clearly, P waves will be absent.

Atrioventricular conduction

Fortunately, the AV node cannot conduct every atrial impulse to the ventricles: if it could, ventricular fibrillation would result! Some impulses are totally blocked. Others only partially penetrate the AV node. They will not therefore activate the ventricles but may block or delay succeeding impulses. This process of ‘concealed conduction’ is responsible for the totally irregular ventricular rhythm that is the hallmark of this arrhythmia.

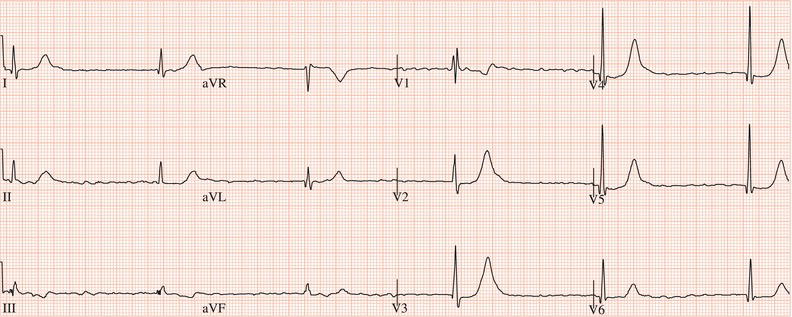

In the absence of P waves, even if f waves are not seen, a totally irregular ventricular rhythm is indicative of atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rhythm is often misdiagnosed. If the characteristic irregular rhythm is remembered, errors will not be made (Figure 6.3). If, however, there is complete AV block, ventricular activity will, of course, be slow and regular (Figure 6.4).

The ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation is dependent on the conducting ability of the AV node, which is itself influenced by the autonomic nervous system. Atrioventricular conduction will be enhanced by sympathetic activity and depressed by high vagal tone. Typically, ventricular rates are rapid, up to 200 beats/min, when the patient is active, and are slow when the patient is at rest or asleep.

Figure 6.3 Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response (heart rate 180 beats/min). The ventricular rhythm is totally irregular. f waves are not obvious.

Figure 6.4 Atrial fibrillation with complete AV block. The ventricular rhythm is regular: rate 39 beats/min.

Intraventricular conduction

Ventricular complexes during atrial fibrillation are normal in duration unless there is established bundle branch block (Figure 6.5), Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome (Chapter 10) or aberrant intraventricular conduction, i.e. rate-related bundle branch block.

Aberrant intraventricular conduction

Aberrant conduction is the result of differing recovery periods of the two bundle branches. An early atrial impulse may reach the ventricles when one bundle branch is still refractory to excitation following the previous cardiac cycle but the other is capable of conduction. The resultant ventricular complex will have a bundle branch block configuration. Because the right bundle usually has the longer refractory period, aberrant conduction commonly leads to right bundle branch block. The duration of the refractory periods of the bundle branches is related to the preceding cycle length. Thus, aberration is likely to occur when a short cycle succeeds a long cycle (Figures 6.6, 6.7): the ‘Ashman phenomenon’. Sometimes a series of aberrantly conducted beats will be misdiagnosed as paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia (see Figure 6.10). However, even though the rate is rapid there will be marked irregularity in the cycle length, and why should there be ‘bursts’ of a second arrhythmia during atrial fibrillation?

Figure 6.5 Atrial fibrillation with established left bundle branch block. The ventricular rhythm is totally irregular.

Figure 6.6 Atrial fibrillation. After seven normally conducted ventricular complexes, there are two complexes with right bundle branch block configuration (upper trace is lead V1).

Figure 6.7 An atrial ectopic beat superimposed on the T wave of the third sinus beat initiates atrial fibrillation. Second and third complexes during atrial fibrillation are aberrantly conducted.

Initiation

Atrial fibrillation is usually initiated by an atrial extrasystole (Figure 6.7). Sometimes atrial flutter or AV re-entrant tachycardia degenerate into atrial fibrillation.

P waves absent

f waves usually seen in at least some leads

Totally irregular

QRS duration normal unless persistent or rate-related bundle branch block

Causes

The most common causes are damaged or disordered heart muscle caused by myocardial infarction, hypertension or cardiomyopathy; heart valve disease; hyperthyroidism; and sick sinus syndrome. In many cases, atrial fibrillation is idiopathic, i.e. there is no demonstrable cause.

Coronary artery disease, i.e. the presence of a coronary stenosis, does not per se cause atrial fibrillation. However, the arrhythmia often results from myocardial infarction, both acutely and in the long term, and is an indicator of extensive myocardial damage.

Many of the causes can be identified or excluded by clinical examination, electrocardiography and echocardiography. Measurement of serum thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone is necessary to exclude hyperthyroidism. Ambulatory electrocardiography may be required where sick sinus syndrome is a possibility.

Acute and past myocardial infarction

Dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies

Hypertension

Myocarditis and pericarditis

Heart valve disease, especially rheumatic mitral valve disease

Atrial septal defect

Cardiac and thoracic surgery

Constrictive pericarditis

Sick sinus syndrome

Atrioventricular junctional re-entrant tachycardias

Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

Hyperthyroidism

Chronic obstructive airways disease

Chest infection

Carcinoma lung

Pulmonary embolism

Acute and chronic alcohol abuse

Obesity

High-endurance sport training

Familial, i.e. genetically determined (rare)

Prevalence

Prevalence increases with age. In a survey of male civil servants in the United Kingdom, atrial fibrillation was found in 0.16%, 0.37% and 1.13% of those aged 40–49 years, 50–59 years and 60–64 years, respectively. In a British general practice 3.7% of patients over 65 years were found to have the arrhythmia.

The Framingham study found that 7.8% of men aged between 65 and 74 years had atrial fibrillation. The prevalence increased to 11.7% in men aged 75–84 years. There is a 26% ‘lifetime’ likelihood of atrial fibrillation. Even in people without a history of heart failure or myocardial infarction the risk is in the order of 15%. The arrhythmia is 1.5 times more common in men than in women.

Prognosis

A major determinant of prognosis is the presence or absence of structural heart disease. For example, myocardial infarction, because atrial fibrillation is usually a result of extensive myocardial damage, indicates a poor prognosis. Most studies have shown that idiopathic atrial fibrillation has a good prognosis.

Classification

- Paroxysmal – atrial fibrillation terminates spontaneously in less than seven days and usually within 48 hours.

- Persistent – atrial fibrillation would continue indefinitely but normal rhythm can be restored by cardioversion.

- Permanent – atrial fibrillation has persisted for more than one year, either because restoration of normal rhythm has failed or because it has not been attempted.

Lone atrial fibrillation

Lone, i.e. idiopathic, atrial fibrillation in younger individuals (< 60 years) is very common. While the prognosis is good and the risk of systemic embolism is low (estimated at 1.3% over a 15-year period), lone atrial fibrillation can cause very troublesome symptoms and great anxiety. Like secondary atrial fibrillation, it may be paroxysmal or persistent.

Paroxysmal lone atrial fibrillation

Some patients will experience only a single or a very occasional episode. Others will experience frequent recurrences, perhaps several times in a day. Paroxysms may last for many hours or stop after only a few seconds (Figure 6.8). With time, in some but not all patients, atrial fibrillation will become persistent. Studies have shown that an episode of atrial fibrillation can lead to alterations in the electrical properties of the atria that encourage perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a process termed ‘electrical remodelling’.

Patients often suffer very troublesome symptoms (Chapter 5). Others, including some with frequent episodes and rapid ventricular rates, will be asymptomatic or merely aware of but not distressed by a rapid heart rate.

In a minority of patients there will be an identifiable precipitating event such as exercise, vomiting, alcohol or fatigue. One form of paroxysmal lone atrial fibrillation has been attributed to high vagal activity: the arrhythmia always starts at rest or during sleep (Figure 6.9).

Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree