Chapter 1 Assessment and investigation of patients’ problems

INTRODUCTION

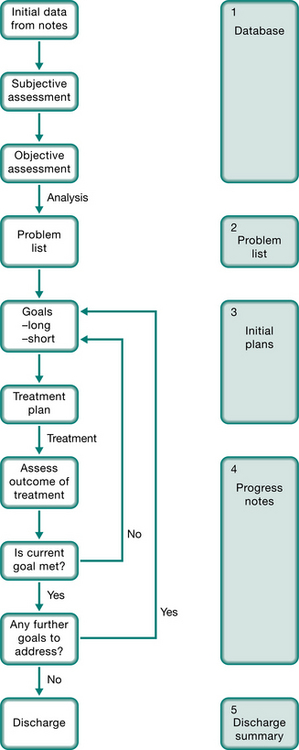

The POMR is now widely used as the method of recording the assessment, management and progress of a patient. It is divided into five sections, as shown in Figure 1.1 and summarized below.

Database. Here personal details, medical history, relevant social history, results of investigations and tests, together with the physiotherapist’s assessment of the patient are recorded.

Database. Here personal details, medical history, relevant social history, results of investigations and tests, together with the physiotherapist’s assessment of the patient are recorded. Problem list. This is a concise list of the patient’s problems, compiled after the assessment is complete. Problems are not always written in order of priority. The list includes problems both amenable to physiotherapy and problems that must be taken into consideration during treatment. The resolution of problems and the appearance of new ones are noted appropriately.

Problem list. This is a concise list of the patient’s problems, compiled after the assessment is complete. Problems are not always written in order of priority. The list includes problems both amenable to physiotherapy and problems that must be taken into consideration during treatment. The resolution of problems and the appearance of new ones are noted appropriately. Initial plan and goals. A treatment plan is formulated to address the physiotherapy-related problems, with consideration given to the patient’s other problems. Long- and short-term goals are then formulated. Long-term goals are what the patient and the physio-therapist want to achieve finally, and should relate to the problems. Short-term goals are the stages by which the long-term goals should be achieved.

Initial plan and goals. A treatment plan is formulated to address the physiotherapy-related problems, with consideration given to the patient’s other problems. Long- and short-term goals are then formulated. Long-term goals are what the patient and the physio-therapist want to achieve finally, and should relate to the problems. Short-term goals are the stages by which the long-term goals should be achieved. Progress notes. These are written to document the patient’s progress, especially highlighting any changes. The notes are written in the ‘subjective, objective, analysis, plan’ (SOAP) format for each problem, and provide an up-to-date summary of the patient’s progress.

Progress notes. These are written to document the patient’s progress, especially highlighting any changes. The notes are written in the ‘subjective, objective, analysis, plan’ (SOAP) format for each problem, and provide an up-to-date summary of the patient’s progress.DATABASE

History of presenting condition (HPC) summarizes the patient’s current problems, including relevant information from the medical notes.

History of presenting condition (HPC) summarizes the patient’s current problems, including relevant information from the medical notes. Previous medical history (PMH) summarizes the entire list of medical and surgical problems that the patient has had in the past. It may be written in disease- specific groupings or as a chronological account.

Previous medical history (PMH) summarizes the entire list of medical and surgical problems that the patient has had in the past. It may be written in disease- specific groupings or as a chronological account. Drug history (DH) is a list of the patient’s current medications (including dosage) taken from the medication charts. Drug allergies should also be noted.

Drug history (DH) is a list of the patient’s current medications (including dosage) taken from the medication charts. Drug allergies should also be noted. Family history (FH) includes a list of any major diseases suffered by members of the immediate family.

Family history (FH) includes a list of any major diseases suffered by members of the immediate family. Social history (SH) provides a picture of the patient’s social situation. It is important to specifically question the patient about the level of support available at home, and to gain an idea of the patient’s expected contribution to household duties. The layout of the patient’s home should also be ascertained with particular emphasis on stairs. Occupation and hobbies, both past and present, give further information about the patient’s lifestyle. Finally, history of smoking and alcohol use should be noted.

Social history (SH) provides a picture of the patient’s social situation. It is important to specifically question the patient about the level of support available at home, and to gain an idea of the patient’s expected contribution to household duties. The layout of the patient’s home should also be ascertained with particular emphasis on stairs. Occupation and hobbies, both past and present, give further information about the patient’s lifestyle. Finally, history of smoking and alcohol use should be noted. Patient examination includes all information collected in the physiotherapist’s subjective and objective assessment of the patient.

Patient examination includes all information collected in the physiotherapist’s subjective and objective assessment of the patient. Test results contain any significant findings as they become available. These may include arterial blood gases, spirometry, blood tests, sputum analysis, chest radiographs, computed tomography (CT) and any other relevant tests (e.g. hepatitis B positive).

Test results contain any significant findings as they become available. These may include arterial blood gases, spirometry, blood tests, sputum analysis, chest radiographs, computed tomography (CT) and any other relevant tests (e.g. hepatitis B positive).Subjective assessment

With each of these symptoms, enquiries should be made concerning:

duration – both the absolute time since first recognition of the symptom (months, years) and the duration of the present symptoms (days, weeks)

duration – both the absolute time since first recognition of the symptom (months, years) and the duration of the present symptoms (days, weeks)Breathlessness

Breathlessness is the subjective awareness of an increased work of breathing. It is the predominant symptom of both cardiac and respiratory disease. It also occurs in anaemia where the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood is reduced, in neuromuscular disorders where the respiratory muscles are affected, and in metabolic disorders where there is a change in the acid–base equilibrium (Chapter 3) or metabolic rate (e.g. hyperthyroid disorders). Breathlessness is also found in hyperventilation syndrome or dysfunctional breathing where psychological factors (e.g. anxiety) may be contributory factors.

Comparison of the severity of breathlessness between patients is difficult because of differences in perception and expectations. To overcome these difficulties, numerous gradings have been proposed. The New York Heart Association classification of breathlessness, shown in Box 1.1, was developed for patients with cardiac disease, but is also applicable to respiratory patients. The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale (Borg 1982) is another scale that is frequently used for both respiratory and cardiac patients. No scale is universal and it is important that all staff within one institution use the same scale.

Box 1.1 The New York Heart Association classification of breathlessness

Breathlessness is usually worse during exercise and better with rest. An exception is hyperventilation syndrome where breathlessness may improve with exercise. Two patterns of breathlessness have been given specific names:

Sputum

In a normal adult, up to 100 ml of tracheobronchial secretions are produced daily and cleared subconsciously by swallowing. Sputum is the excess tracheobronchial secretions that are cleared from the airways by coughing or huffing. It may contain mucus, cellular debris, microorganisms, blood and foreign particles. Questioning should determine the colour, consistency and quantity of sputum produced each day. This may clarify the diagnosis and the severity of disease (Table 1.1).

| Description | Causes | |

|---|---|---|

| Saliva | Clear watery fluid | |

| Mucoid | Opalescent or white | Chronic bronchitis without infection, asthma |

| Mucopurulent | Slightly discoloured, but not frank pus | Bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, pneumonia |

| Purulent | Thick, viscous: | |

| Frothy | Pink or white | Pulmonary oedema |

| Haemoptysis | Ranging from blood specks to frank blood, old blood (dark brown) | Infection (tuberculosis, bronchiectasis), infarction, carcinoma, vasculitis, trauma, also coagulation disorders, cardiac disease |

| Black | Black specks in mucoid secretions | Smoke inhalation (fires, tobacco, heroin), coal dust |

A number of grading systems for mucoid, mucopurulent, purulent sputum have been proposed. For example, Miller (1963) suggested:

| M1 | mucoid with no suspicion of pus |

| M2 | predominantly mucoid, suspicion of pus |

| P1 | 1/3 purulent, 2/3 mucoid |

| P2 | 2/3 purulent, 1/3 mucoid |

| P3 | >2/3 purulent. |

Chest pain

Pericarditis may cause pain similar to angina or pleurisy.

A differential diagnosis of chest pain is given in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Syndromes of chest pain

| Condition | Description | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | ||

| Pleurisy | Sharp, stabbing, rapid onset, limits inspiration, well localized, often ‘catches’ at a certain lung volume, not tender on palpation | Pleural infection or inflammation of the pleura, trauma (haemothorax), malignancy |

| Pulmonary embolus | Usually has pleuritic pain, with or without severe central pain | Pulmonary infarction |

| Pneumothorax | Severe central chest discomfort, with or without pleuritic component, severity depends on extent of mediastinal shift | Trauma, spontaneous, lung diseases (e.g. cystic fibrosis, AIDS) |

| Tumours | May mimic any form of chest pain, depending on site and structures involved | Primary or secondary carcinoma, mesothelioma |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Rib fracture | Localized point tenderness, often sudden onset, increases with inspiration | Trauma, tumour, cough fractures (e.g. in chronic lung diseases, osteoporosis) |

| Muscular | Superficial, increases on inspiration and some body movements, with or without palpable muscle spasm | Trauma, unaccustomed exercise (excessive coughing during exacerbations of lung disease), accessory muscles may be affected |

| Costochondritis (Tietze’s syndrome) | Localized to one or more costochondral joints, with or without generalized, non-specific chest pain | Viral infection |

| Neuralgia | Pain or paraesthesia in a dermatomal distribution | Thoracic spine dysfunction, tumour, trauma, herpes zoster (shingles) |

| Cardiac | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease (angina or infarct) | Dull, central, retrosternal discomfort like a weight or band with or without radiation to the jaw and/or either arm, may be associated with palpitations, nausea or vomiting | Myocardial ischaemia, onset at rest is more suggestive of infarction |

| Pericarditis | Often retrosternal, exacerbated by respiration, may mimic cardiac ischaemia or pleurisy, often relieved by sitting | Infection, inflammation, trauma, tumour |

| Mediastinum | ||

| Dissecting aortic aneurysm | Sudden onset, severe, poorly localized central chest pain | Trauma, atherosclerosis, Marfan’s syndrome |

| Oesophageal | Retrosternal burning discomfort, but can mimic all other pains, worse lying flat or bending forward | Oesophageal reflux, trauma, tumour |

| Mediastinal shift | Severe, poorly localized central discomfort | Pneumothorax, rapid drainage of a large pleural effusion |

Incontinence

Incontinence is a problem that is often aggravated by chronic cough (Orr et al 2001, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2004, Thakar & Stanton 2000). Coughing and huffing increase intra-abdominal pressure, which may precipitate urine leakage. Fear of this may influence compliance with physiotherapy. Thus, identification and treatment of incontinence is important. Questions may need to be specific to elicit this symptom: ‘When you cough, do you find that you leak some urine? ‘Does this interfere with your physiotherapy?’

Functional ability

It is important to assess the patient as a whole, enquiring about their daily activities. If the patient is employed, what does the job actually entail? For example, a surveyor may sit behind a desk all day, or may be climbing 25-storey buildings. The home situation should also be documented, in particular the number of stairs to the front door and within the house. With whom does the patient live? What roles does the patient perform in the home (shopping, housework, cooking)? Finally, questions concerning activities and recreation often reveal areas where significant improvements in quality of life can be made.

Quality of life

Assessment of quality of life (QOL) is becoming increasingly important to assess the impact of disability on the patient and as a measure of response to treatment. QOL scales measure the effect of an illness and its management upon a patient as perceived by the patient. Often there is little correlation between physiological measures (e.g. lung function) and QOL. A number of both generic, for example SF-36 (Ware & Sherbourne 1992) and disease-specific QOL scales are available which allow data to be gathered principally by self-report questionnaires or interview. QOL scales available for assessment of patients with respiratory or cardiovascular disease are reviewed elsewhere (Juniper et al 1999, Kinney et al 1996, Mahler 2000, Pashkow et al 1995). The choice of a QOL measure requires an evaluation of QOL scales with respect to their reliability, validity, responsiveness and appropriateness (Aaronson 1989).

Objective assessment

Objective assessment is based on examination of the patient, together with the use of tests such as spirometry, arterial blood gases and chest radiographs. Although a full examination of the patient should be available from the medical notes, it is worthwhile to make a thorough examination at all times, as the patient’s condition may have changed since the last examination, and the physiotherapist may need greater detail of certain aspects than is available from the notes. A good examination will provide an objective baseline for future measurement of the patient’s progress. By developing a standard method of examination, the findings are quickly assimilated and the physiotherapist remains confident that nothing has been omitted. This chapter refers mainly to assessment of the adult patient, although much of the information is also relevant to the paediatric population. Specific details for the assessment of infants and children and normal values can be found in the relevant paediatric sections (Chapters 9 & 10).

General observation

In the intensive care patient there are a number of further features to be observed. The level of ventilatory support must be ascertained. This includes both the mode of ventilation (e.g. supplemental oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure, intermittent positive pressure ventilation) and the route of ventilation (mask, endotracheal tube, tracheostomy). The level of cardiovascular support should also be noted, including drugs to control blood pressure and cardiac output, pacemakers and other mechanical devices. The patient’s level of consciousness should also be noted. Any patient with a decreased level of consciousness is at risk of aspiration and retention of pulmonary secretions. In those patients who are not pharmacologically sedated, the level of consciousness is often measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale (Box 1.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree