Assessment

A complete respiratory assessment will provide you with essential information about the thorax and lungs. The assessment should include obtaining a careful history and performing a complete physical examination. Knowing the basic structures and functions of the respiratory system will help you perform a comprehensive respiratory assessment and recognize abnormalities.

HEALTH HISTORY

Any assessment begins with a health history that includes exploration of the patient’s chief complaints. Build the health history by asking open-ended questions. Ask these questions systematically to avoid overlooking important information. If necessary, conduct the interview in several short sessions, depending on the severity of the patient’s condition, his expectations, and staffing constraints.

Most information obtained about a child will come from the family. Sometimes the chief complaint the parent expresses may not be the actual reason she’s seeking medical attention.

Always ask the parent if she has other concerns about the child. Asking such questions as “Was there anything else you wanted to ask me today?” or “Do you have any other concerns?” may invite the parent to share her concerns.

The adolescent child usually responds to those who pay attention to him. Showing interest in the adolescent (and not his problem) early in the interview will help build trust and begin a rapport with

him. Start the interview by first informally asking about his friends, school, or hobbies. When rapport has been established, you can return to more open-ended questioning.

him. Start the interview by first informally asking about his friends, school, or hobbies. When rapport has been established, you can return to more open-ended questioning.

During the interview, establish a rapport with the patient by explaining who you are and what you’ll do. The quantity and quality of the information gathered depends on the relationship you build with the patient. Try to gain his trust by being sensitive to his concerns and feelings. Be alert to nonverbal responses that support or contradict his verbal responses. He may, for example, deny chest pain verbally but reveal it through his facial expressions. If the patient’s verbal and nonverbal responses contradict each other, explore this with him to clarify your assessment.

Chief complaint

Ask the patient to tell you about his chief complaint. Use such questions as “When did you first notice you weren’t feeling well?” and “What has happened since then that brings you here today?” Because many respiratory disorders are chronic, be sure to ask him how the latest episode compared with the previous episode, and what relief measures were helpful or unhelpful.

Current health history

The current health history includes the patient’s biographic data and an analysis of his symptoms. Determine the patient’s age, gender, marital status, occupation, education, religion, and ethnic background. These factors provide clues to potential risks and to the patient’s interpretation of his respiratory condition. Advanced age, for example, suggests physiologic changes such as decreased vital capacity. Alternatively, the patient’s occupation may alert you to problems related to hazardous materials. Ask him for the name, address, and phone number of a relative who can be contacted in an emergency.

After obtaining biographic data, ask the patient to describe his symptoms chronologically. Concentrate on the symptoms’:

onset—the first occurrence of symptoms and if they appeared suddenly or gradually

incidence—the frequency of his symptoms; for example, if the pain is constant, intermittent, steadily worsening, or crescendo-decrescendo

duration—the time period of his symptoms; ask him to use precise terms to describe his answers, such as “30 minutes after meals,” “twice per day,” or “for 3 hours.”

Next, ask the patient to characterize his symptoms. Have him describe:

aggravating factors—the cause of increased intensity; for example, if he has dyspnea, ask him how many feet he can walk before he feels short of breath

alleviating factors—the relieving measures; determine if he’s using any home remedies, such as over-the-counter (OTC) medications, alternative therapies, or a change in sleeping position

associated factors—the other symptoms that occur at the same time as the primary symptom

location—the area where he experiences the symptom; ask him to pinpoint it and determine if it radiates to other areas

quality—the feeling that accompanies the symptom and if he has experienced similar symptoms in the past; ask him to characterize the symptom in his own words and document his description, including the words he chooses to describe pain, for example, sharp, stabbing, or throbbing

duration—the length of time symptoms last

setting—the place where the patient was when the symptom occurred; ask him what he was doing and who was with him.

Be sure to document your findings.

A patient with a respiratory disorder may complain of dyspnea, fatigue, cough, sputum production, wheezing, and chest pain. Here are some helpful assessment techniques to gain information about each of these signs and symptoms.

DYSPNEA

Dyspnea, or shortness of breath, occurs when breathing is inappropriately difficult for the activity that the patient is performing. When ventilation is disturbed and ventilatory demands exceed the actual or perceived capacity of the lungs to respond, the patient becomes short of breath. In addition, dyspnea is caused by decreased lung compliance, disturbances in the chest bellows system, airway obstruction, or exogenous factors such as obesity.

GRADING DYSPNEA

To assess dyspnea as objectively as possible, ask your patient to briefly describe how various activities affect his breathing. Then document his response using this grading system.

Grade 0—Not troubled by breathlessness except with strenuous exercise

Grade 1—Troubled by shortness of breath when hurrying on a level path or walking up a slight hill

Grade 2—Walks more slowly on a level path because of breathlessness than people of the same age or has to stop to breathe when walking on a level path at his own pace

Grade 3—Stops to breathe after walking about 100 yards (91.4 m) on a level path

Grade 4—Too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing or undressing

Obtain the patient’s history of dyspnea by using several scales. Ask the patient to rate his usual level of dyspnea on a scale of 0 to 10, in which 0 means no dyspnea and 10 means the worst he has experienced. Then ask him to rate the level that day. Another method to assess dyspnea is to count the number of words the patient speaks between breaths. A normal individual can speak 10 to 12 words. A severely dyspneic patient may speak only 1 to 2 words per breath.

Ask the patient what he does to relieve the dyspnea and how well those measures work. (See Grading dyspnea.)

To find out if the dyspnea stems from pulmonary disease, ask the patient about its onset and severity:

A sudden onset may indicate an acute problem, such as pneumothorax or pulmonary embolus, or may result from anxiety caused by hyperventilation.

A gradual onset suggests a slow, progressive disorder such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), whereas acute intermittent attacks may indicate asthma.

Normally, an infant’s respirations are abdominal, gradually changing to costal by age 7. Suspect dyspnea in an infant who breathes costally, in an older child who breathes abdominally, or in a child who uses accessory muscles to aid in breathing.

ORTHOPNEA

Orthopnea is increased dyspnea when the patient is in a supine position. It’s traditionally measured in “pillows”—as in the number (usually one to three) of pillows needed to prop the patient before dyspnea resolves. A better method is to record the degree of head elevation at which dyspnea is relieved using a goniometer. This device is used by physical therapists to determine range of motion and may be used to measure a patient’s orthopnea, for example, “relieved at 35 degrees.”

Orthopnea is commonly associated with:

asthma

COPD

diaphragmatic paralysis

left-sided heart failure

obesity

pulmonary hypertension

fatigue.

Patients with respiratory disorders experience fatigue. Fatigue is subjective and varies with the severity of the disorder and daily activities. Fatigue can be measured by using a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no fatigue and 10 being the worst fatigue experienced. Daily activities are prioritized by the daily level of fatigue. Worsening fatigue usually indicates worsening respiratory conditions.

COUGH

If the patient is experiencing a cough, ask him these questions: Is the cough productive? If the cough is a chronic problem, has it changed recently? If so, how? What makes the cough better? What makes it worse?

Also investigate the characteristics of the cough:

changing sputum, from white to yellow or green—suggesting a bacterial infection

chronic productive with mucoid sputum—signaling asthma or chronic bronchitis

congested—suggesting a cold, pneumonia, or bronchitis

dry—signaling a cardiac condition

hacking—signaling pneumonia

increased amounts of mucoid sputum—suggesting acute tracheobronchitis or acute asthma

occurring in late afternoon—indicating exposure to irritants

occurring in the early morning—indicating chronic airway inflammation, possibly from cigarette smoke

occurring in the evening—suggesting chronic postnasal drip or sinusitis

severe—it disrupts daily activities and causes chest pain or acute respiratory distress.

In children, evaluate a cough for these characteristics:

barking, signaling croup

nonproductive, indicating foreign body obstruction, asthma, pneumonia, acute otitis media, or early cystic fibrosis

productive, accompanied by thick or excessive secretions, suggesting respiratory distress, asthma, bronchiectasis, bronchitis, cystic fibrosis, or pertussis.

SPUTUM PRODUCTION

When a patient produces sputum, ask him to estimate the amount produced in teaspoons or some other common measurement. Find out what time of day he usually coughs and the color and consistency of his sputum. Ask if his sputum is a chronic problem and if it has recently changed. If it has, ask him how. Also ask if he coughs up blood (hemoptysis); if so, find out how much and how often.

Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis (coughing up blood) may result from violent coughing or from serious disorders, such as pneumonia, lung cancer, lung abscess, tuberculosis (TB), pulmonary embolism, bronchiectasis, and left-sided heart failure. If the hemoptysis is mild (sputum streaked with blood), reassure the patient and be sure to ask when he first noticed it and how often it occurs.

If hemoptysis is severe, causing frank bleeding, place the patient in a semirecumbent position, note pulse rate, blood pressure, and general condition. When the patient’s condition stabilizes, ask whether he has ever experienced similar bleeding. (See Hemoptysis or hematemesis?)

If an elderly patient experiences hemoptysis, check his medication history for use of anticoagulants. Changes in diet or medications, including OTC drugs and herbal supplements,

may be necessary because they may alter the anticoagulant effect of Coumadin.

may be necessary because they may alter the anticoagulant effect of Coumadin.

In children, hemoptysis may stem from Goodpasture’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis or, rarely, idiopathic primary pulmonary hemosiderosis. In rare cases, pulmonary hemorrhage of unknown cause occurs in the first 2 weeks of life; the prognosis in these patients is poor.

HEMOPTYSIS OR HEMATEMESIS?

If a patient begins bleeding from his mouth, determine if he’s experiencing hemoptysis, which is coughing up blood from the lungs; hematemesis, which is vomiting blood from the stomach; or bleeding from a site in the upper respiratory tract. Compare the conditions based on the signs and symptoms listed here.

Hemoptysis

Bright red or pink, frothy blood

Blood mixed with sputum

Negative litmus paper test of blood (paper remains blue)

Hematemesis

Dark red blood, possibly with coffeeground appearance

Blood mixed with food

Positive litmus paper test of blood (paper turns pink)

Upper respiratory tract bleeding

Oral sources

Blood mixed with saliva

Evidence of mouth or tongue laceration

Negative litmus paper test of blood

Nasal or sinus source

Tickling sensation in nasal passages

Sniffing behavior

Negative litmus paper test of blood

SLEEP DISTURBANCE

Sleep disturbances may be related to obstructive sleep apnea or other sleep disorders requiring additional evaluation.

If the patient complains of being drowsy or irritable in the daytime, ask him how many hours of continuous sleep he gets at night. Ask him if he awakens during the night and if his family complains about his snoring or restlessness.

WHEEZING

If a patient wheezes, initially determine the severity of the condition.

If the patient is in distress, immediately assess his ABCs—airway, breathing, and circulation. Does he have an open airway? Is he breathing? Does he have a pulse? If any of these is absent, call for help and start cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Next, quickly check for signs of impending crisis:

Is the patient having difficulty breathing?

Is he using accessory muscles to breathe? If chest excursion is less than the normal 1 1/8″ to 2″ (3 to 5 cm), he’ll use accessory muscles when he breathes. Look for shoulder elevation, intercostal muscle retraction, and use of scalene and sternocleidomastoid muscles.

Has his level of consciousness (LOC) diminished?

Is he confused, anxious, or agitated?

Does he change his body position to ease breathing?

Does his skin look pale, diaphoretic, or cyanotic?

If the patient isn’t in acute distress, ask him these questions: When does wheezing occur? What makes you wheeze? Do you wheeze loudly enough for others to hear? What helps stop your wheezing?

Children are especially susceptible to wheezing due to their small airways, which are prone to rapid obstruction.

CHEST PAIN

If the patient has chest pain, ask him where the pain is located. Have the patient rate the pain in a scale from 0 to 10. Ask him what the pain feels like, if it’s sharp, stabbing, burning, or aching. Find out if it radiates to another area in his body and, if so, where. Ask the patient how long the pain lasts, what causes it to occur, and what makes it better.

When the patient is describing his chest pain, attempt to determine the type of pain he’s experiencing:

chest wall pain that’s localized and tender (indicates an infection or inflammation of the chest wall, intercostal nerves, or intercostal muscles or, possibly, blunt chest trauma)

esophageal pain that’s a burning sensation that intensifies with swallowing (indicates local inflammation)

pleural pain that’s stabbing, knifelike, and increases with deep breathing or coughing (associated with pulmonary infarction, pneumothorax, or pleurisy)

substernal pain that’s a sharp, stabbing pain in the middle of his chest (indicates pneumonia or spontaneous pneumothorax)

tracheal pain that’s a burning sensation that intensifies with deep breathing or coughing (suggests oxygen toxicity or aspiration).

Regardless of the type of pain the patient describes, remember to assess associated factors, such as breathing, body position, and ease or difficulty of movement.

Past health history

The information gained from the patient’s past health history helps in understanding his current symptoms. It also helps to identify patients at risk for developing respiratory difficulty.

First, focus on identifying previous respiratory problems, such as asthma and COPD. A history of these disorders provides instant clues to the patient’s current condition. Then ask about childhood illnesses.

Infantile eczema, atopic dermatitis, or allergic rhinitis, for example, may precipitate current respiratory problems such as asthma.

Obtain an immunization history, especially of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, which may provide clues about the potential for respiratory disease. A travel history may be useful and should include dates, destinations, and length of stay.

Next, ask what problems in the past caused the patient to see a health care provider or required hospitalization, paying particular attention to respiratory problems. For example, chronic sinus infection or postnasal discharge may lead to recurrent bronchitis, and repeated episodes of pneumonia involving the same lung lobe may accompany bronchogenic carcinoma.

Ask the patient to describe the prescribed treatment, whether he followed the treatment plan, and whether the treatment helped. Determine whether he has suffered any traumatic injuries. If he has, note when they occurred and how they were treated.

The history should also include brief personal details. Ask the patient if he smokes; if he does, ask when he started and how many packs of cigarettes he smokes per day. By calculating his smoking in pack-years, you can assess his risk of respiratory

disease. To estimate pack-years, use this simple formula: number of packs smoked per day multiplied by the number of years the patient has smoked. For example, a patient who has smoked 2 packs of cigarettes per day for 42 years has accumulated 84 pack-years.

disease. To estimate pack-years, use this simple formula: number of packs smoked per day multiplied by the number of years the patient has smoked. For example, a patient who has smoked 2 packs of cigarettes per day for 42 years has accumulated 84 pack-years.

Remember to ask about the patient’s alcohol use and about his diet because nutritional status commonly influences a patient’s risk of respiratory infection.

It’s also important to obtain an allergy history. Allergies could include airborne, food, drug, and insect bites. Determine what the allergic reaction is, such as runny nose, sneezing, coughing, or other respiratory complication such as wheezing. Another component of the past health history includes medications the patient is taking. These include prescribed, OTC, herbal, and recreational drugs. All of these have adverse effects, some of them adversely affecting the respiratory system. It’s important to note medications that the patient is allergic to. This information needs to be verified and documented properly.

Family history

Obtaining a family history helps determine whether a patient is at risk for hereditary or infectious respiratory diseases. First, ask if any of his immediate blood relatives, such as parents, siblings, and children, have had cancer, sickle cell anemia, heart disease, or a chronic illness, such as asthma and emphysema. Remember that diabetes can lead to cardiac and, possibly, respiratory problems. If an immediate relative has one or more of these disorders, ask for more information about the patient’s maternal and paternal grandparents, aunts, and uncles.

Be sure to determine whether the patient lives with anyone who has an infectious disease, such as influenza or TB.

Psychosocial history

Ask the patient about his psychosocial history to assess his lifestyle. Be sure to cover his home, community, and other environmental factors that might influence how he deals with his respiratory problems. For example, people who work in mining, construction, or chemical manufacturing are commonly exposed to environmental irritants. Also ask about interpersonal relationships, mental health status, stress management, and coping

style. Keep in mind that a patient’s sexual habits or drug use may be connected with pulmonary disorders related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

style. Keep in mind that a patient’s sexual habits or drug use may be connected with pulmonary disorders related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

Any patient can develop a respiratory disorder. Using a systematic assessment enables the practitioner to detect subtle or obvious respiratory changes. The depth of the assessment will depend on several factors, including the patient’s primary health problem and his risk of developing respiratory complications.

A physical examination of the respiratory system follows four steps: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Before you begin, make sure the examination room is well lit and warm.

Make a few observations about the patient as soon as you enter the room. Note how he’s seated, which will most likely be the position most comfortable for him. Take note of his level of consciousness and general appearance. Does he appear relaxed? Anxious? Uncomfortable? Is he having trouble breathing? Include those observations in your final assessment.

Assess the patient’s ability to speak. If he’s unable to speak, suspect a complete airway obstruction.

When you’re ready to begin the physical assessment, seat the patient in a position that allows access to the anterior and posterior thorax. Provide an examination gown that offers easy access to the chest and back without requiring unnecessary exposure. Make sure the patient isn’t cold because shivering can alter breathing patterns.

If the patient can’t sit up, place him in the semi-Fowler position to assess the anterior chest wall and the side-lying position to assess the posterior thorax. Keep in mind that these positions may cause some distortion of findings.

If the patient is an infant or a small child, assess him while he’s seated on the parent’s lap.

When performing the physical assessment, it may be easier to inspect, palpate, percuss, and auscultate the anterior chest before the posterior. However, this section covers inspection of the entire chest, then palpation, percussion, and auscultation of the entire chest.

Chest inspection

To assess respiratory function, determine the rate, rhythm, and quality of the patient’s respirations and inspect his chest configuration, tracheal position, chest symmetry, skin condition, nostrils (for flaring), and accessory muscle use. Accomplish this by observing the patient’s breathing and inspecting his anterior and posterior thorax. Note all abnormal findings.

RESPIRATORY PATTERN

To find the patient’s respiratory rate, count for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 to give you the rate per minute. If the rhythm is irregular, less than 12 breaths/minute or more than 20 breaths/minute, count for a full minute. Don’t tell him what you’re doing, or he might alter his natural breathing pattern. Adults normally breathe at a rate of 12 to 20 breaths/minute.

An infant’s respiratory rate may reach about 40 breaths/minute.

The respiratory pattern should be even, coordinated, and regular, with occasional sighs.

Men, children, and infants usually use abdominal, or diaphragmatic, breathing. Athletes and singers do as well. Most women, however, usually use chest, or intercostal, breathing.

Paradoxical movement of the chest wall may appear as an abnormal collapse of part of the chest wall. The abnormal part of the chest wall contracts (sucks in) during inspiration and expands (pushes out) during exhalation.

Abnormal respiratory patterns

Identifying an abnormal respiratory pattern can help you assess a patient’s respiratory status and his overall condition. (See Recognizing abnormal respiratory patterns.)

Tachypnea

Tachypnea is a respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths/minute; usually the breaths are shallow. It’s commonly seen in patients with restrictive lung disease, pain, sepsis, obesity, anxiety, and respiratory distress. Fever is another possible cause. The respiratory rate my increase by 4 breaths/minute for every 1° F (0.6° C) increase in body temperature.

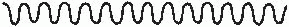

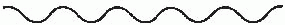

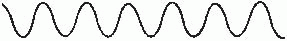

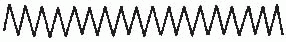

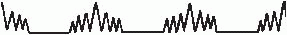

RECOGNIZING ABNORMAL RESPIRATORY PATTERNS

To help you better recognize abnormal respiratory patterns, illustrated below are typical characteristics of the more common ones.

Kussmaul’s respirations

Rapid, deep breathing without pauses; in adults, more than 20 breaths/minute; breathing usually sounds labored with deep breaths that resemble sighs

|

Cheyne-Stokes respirations

Breaths that gradually become faster and deeper than normal, then slower, during a 30- to 170-second period; alternates with 20- to 60-second periods of apnea

|

Bradypnea

Bradypnea is a respiratory rate below 12 breaths/minute. It’s commonly noted just before a period of apnea or full respiratory arrest.

Patients with bradypnea might have central nervous system (CNS) depression as a result of excessive sedation, tissue damage, diabetic coma, or any situation in which the brain’s respiratory center is depressed. Note that the respiratory rate is usually slower during sleep.

Apnea

Apnea is the absence of breathing. Periods of apnea may be short and occur sporadically, such as in Cheyne-Stokes respiration or other abnormal respiratory patterns. This condition may be life threatening if periods of apnea last long enough and should be addressed immediately.

Hyperpnea

Hyperpnea is characterized by deep breathing. It occurs in patients who exercise and those who have metabolic acidosis, are highly anxious, or are experiencing pain.

Kussmaul’s respirations

Kussmaul’s respirations are rapid and deep, with sighing breaths. This type of breathing occurs in patients with metabolic acidosis, especially when associated with diabetic ketoacidosis, as the respiratory system tries to lower the carbon dioxide level in the blood and restore it to normal pH.

Cheyne-Stokes respirations

Cheyne-Stokes respirations have a regular cycle of change in the rate and depth of breathing. Respirations are initially shallow. They gradually become deeper and then become shallow again before a period of apnea lasting up to 20 seconds. Then the cycle starts again. This respiratory pattern is seen in patients with heart failure, kidney failure, or CNS damage.

In children and elderly patients during sleep, Cheyne-Stokes respirations may be normal.

Biot’s respirations

Also known as ataxic respirations, Biot’s respirations involve rapid, deep breaths that alternate with abrupt periods of apnea. It’s an ominous sign in the setting of severe CNS damage.

ANTERIOR THORAX

After assessing respiration, inspect the anterior thorax for structural deformities, such as a concave or convex curvature of the anterior chest wall over the sternum. Inspect between and around the ribs for visible sinking of soft tissues (retractions). Assess the patient’s respiratory pattern for symmetry. Look for

abnormalities in skin color or alterations in muscle tone. For future documentation, note the location of abnormalities according to regions delineated by imaginary lines on the thorax.

abnormalities in skin color or alterations in muscle tone. For future documentation, note the location of abnormalities according to regions delineated by imaginary lines on the thorax.

Initially inspect the chest wall to identify the shape of the thoracic cage. In an adult, the lateral diameter of the thorax (from side to side) should be twice the anteroposterior diameter (from front to back).

Note the angle between the ribs and the sternum at the point immediately above the xiphoid process. This angle, called the sternocostal angle, should be less than 90 degrees in an adult; it widens if the chest wall is chronically expanded, as in cases of increased anteroposterior diameter, or barrel chest.

To inspect the anterior chest for symmetry of movement, have the patient lie in a supine position. Stand at the foot of the bed and carefully observe the patient’s quiet and deep breathing for equal expansion of the chest wall.

Watch for abnormal collapse of part of the chest wall during inspiration, along with abnormal expansion of the same area during expiration, which signals paradoxical movement—a loss of normal chest wall function. Also, check whether one portion of the chest wall lags behind the others as the chest moves, which may indicate a progression in the patient’s lung disease.

Next, check for the use of accessory muscles for respiration by observing the sternocleidomastoid, scalene, and trapezius muscles in the shoulders and neck. During normal inspiration and expiration, the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles should easily maintain the breathing process.

In elderly patients, hypertrophy of any of the accessory muscles may indicate frequent abnormal use—although hypertrophy may be normal in a well-conditioned athlete.

Note the position the patient assumes to breathe. A patient who depends on accessory muscles may assume a “tripod position,” where he rests his arms on his knees or on the sides of a chair and supports his head.

Observe the patient’s skin on the anterior chest for any unusual color, lumps, or lesions, and note the location of any abnormality. Unless the patient has been exposed to significant sun or heat, the skin color of the chest should match the rest of the patient’s complexion. A skin abnormality may reflect problems in the underlying structure, so note the location of underlying

ribs and other bones, cartilage, and lung lobes. Also, check for any chest wall scars from previous surgeries. If the patient didn’t mention past surgery during the health history, ask about it now.

ribs and other bones, cartilage, and lung lobes. Also, check for any chest wall scars from previous surgeries. If the patient didn’t mention past surgery during the health history, ask about it now.

POSTERIOR THORAX

To inspect the posterior thorax, observe the patient’s breathing again. If he can’t sit in a backless chair or lean forward against a supporting structure, direct him to lie in a lateral position. Be aware that this may distort the findings in some situations. If the patient is obese, findings may be distorted because he may be unable to fully expand the lower lung from the lateral position, leaving breath sounds on that side diminished.

Assess the posterior chest wall for the same characteristics as the anterior: chest structure, respiratory pattern, symmetry of expansion, skin color and muscle tone, and accessory muscle use. During the examination for chest wall abnormalities, keep in mind that the patient might have completely normal lungs and that they might be cramped within the chest. The patient might have a smaller-than-normal lung capacity and limited exercise tolerance, and he may more easily develop respiratory failure from a respiratory tract infection. Other chest wall abnormalities include:

A barrel chest, which looks like its name implies, is characterized by an abnormally round and bulging chest, with a greater-than-normal front-to-back diameter. It occurs as a result of COPD, indicating that the lungs have lost their elasticity and that the diaphragm is flattened. The patient typically uses accessory muscles when he inhales and easily becomes breathless. You’ll also note kyphosis of the thoracic spine, ribs that run horizontally rather than tangentially, and a prominent sternal angle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree