(1)

Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin Ospedale Molinette, Turin, Italy

Abstract

Arteriovenous fistulas are direct abnormal communications between arteries and veins. They can occur in any location where both vessels run very close to each other.

Arteriovenous fistulas are direct abnormal communications between arteries and veins. They can occur in any location where both vessels run very close to each other.

14.1 Carotid–Cavernous Fistulas

These are the most frequent type of arteriovenous fistulas and are characterized by a direct shunt between the intracavernous segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the surrounding venous plexus of the cavernous sinus. The pathogenesis is commonly a rupture of the artery and vein, after a penetrating or blunt trauma. Spontaneous fistulas can occur: these are commonly due to a rupture of an intracavernous aneurysm, frequently linked to an associated angiodysplasia, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), neurofibromatosis, and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (Kanner et al. 2000). Fistulas resulting from spontaneous dissection of the ICA have been reported (Bradac et al. 1985), and fistulas arising from laceration of the artery during transsphenoidal surgery can also occur.

14.1.1 Clinical Presentation

Carotid–cavernous fistulas are characterized by a typical cavernous sinus syndrome with ophthalmoplegia, visus involvement, pulsating exophthalmos, chemosis, and bruit. The symptoms can appear acutely or slowly, progressively days or weeks after the trauma, or have a spontaneous onset. Commonly adults but sometimes also children can be involved. Ischemia or intracerebral hemorrhage may occur. Similar to dural arteriovenous fistulas involving the cavernous sinus, also in carotid–cavernous fistulas, ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral complications can occur as the result of a connection with the pial veins represented by the pontomesencephalic veins, through bridging veins, the SMCV and DMCV.

14.1.2 Diagnosis and Treatment

The dilated cavernous sinus and superior ophthalmic vein can be easily recognized on CT or MRI. Angiography, however, is essential for a precise diagnosis and in planning treatment. Carotid–cavernous fistulas are high-flow fistulas with a rapid injection on the angiogram of the cavernous sinus. Depending on the location of the fistula and anatomical variant, further drainage can be prevalently directed as follows: anteriorly, in the superior inferior ophthalmic veins, in which the flow is reversed extracranially, draining into the facial vein system; or posteriorly, into the superior–inferior petrosal sinuses. Through intercavernous anastomoses, the contralateral cavernous sinus may be involved. The pontomesencephalic veins, basal vein, and deep and superficial middle cerebral veins also can be involved as a result of anastomoses of the cavernous sinus with these venous channels (see Sect. 9.3.10). In cases of severe lacerations of the ICA, the blood flow passes completely in the venous sector, and on the angiogram no cerebral arteries are recognizable.

The angiographic study consists of a bilateral carotid examination to exclude the possibility of bilateral lesions and to check for a collateral circulation. The external carotid artery should also be selectively examined since in some cases the branches (internal maxillary artery, ascending pharyngeal artery) can be involved. To precisely identify the site of the shunt, a vertebral angiogram with compression of the involved ICA can be very useful.

Endovascular treatment with a detachable balloon to occlude the shunt, which was proposed and developed by Serbinenko (1974) and Debrun et al. (1975a, b), has progressively become the therapy of choice. The treatment is performed today with a balloon or coils, which has led to good clinical and anatomical results, with limited morbidity and mortality (Berenstein and Kricheff 1979; Debrun et al. 1981; Scialfa et al. 1983; Kendall 1983; Lewis et al. 1995; Gupta et al. 2006). An alternative route, introduced by Mullan (1979), Manelfe and Berenstein (1980), Halbach (1988a), and increasingly used today, is the endovascular venous approach through the facial or superior ophthalmic vein or through the inferior petrosal sinus (Figs. 14.1, 14.2, and 14.3).

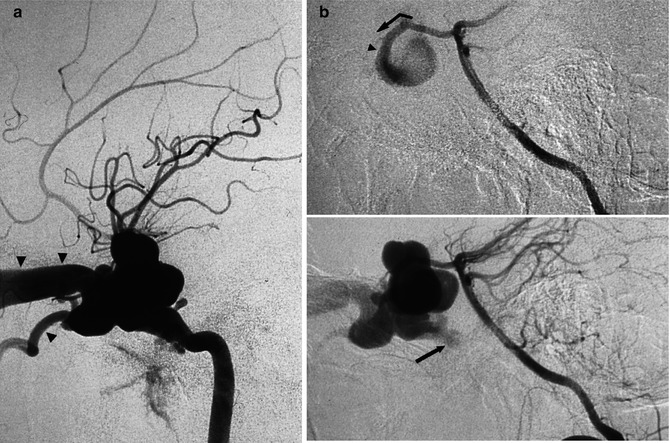

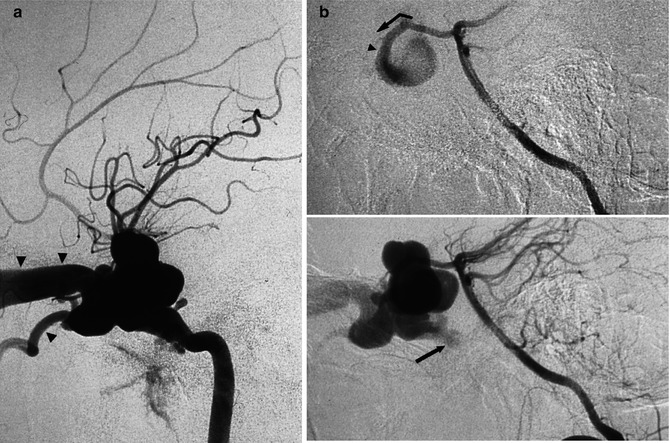

Fig. 14.1

Traumatic carotid–cavernous fistula. (a) Internal lateral carotid angiogram. There is an immediate injection of the dilated and deformed cavernous sinus and filling of the dilated superior (arrowheads) and inferior ophthalmic veins. (b) Lateral vertebral angiogram with compression of the involved internal carotid artery. Through the posterior communicating artery, there is injection of the internal carotid artery and fistula. Site of the shunt (arrowhead). In a later phase, there is a partial injection of the inferior petrosal sinus, which could be thrombosed (arrow)

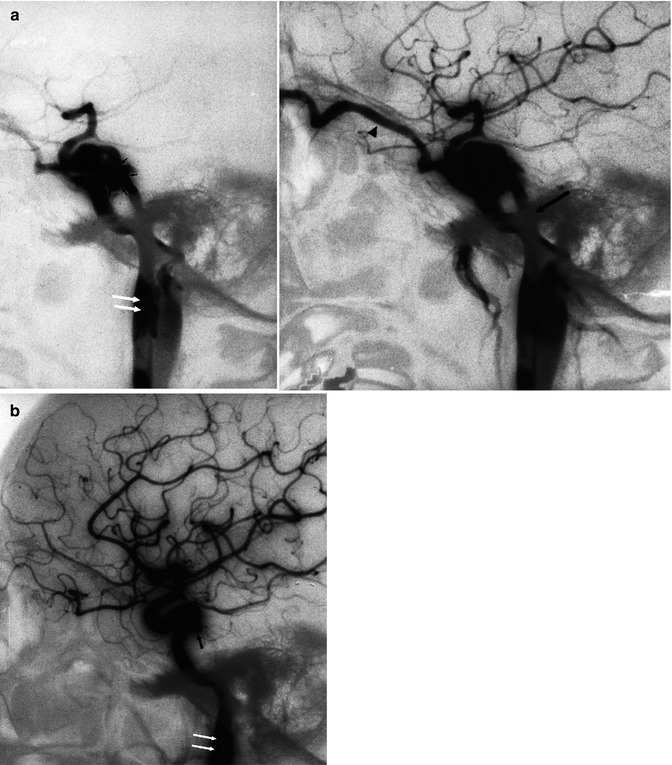

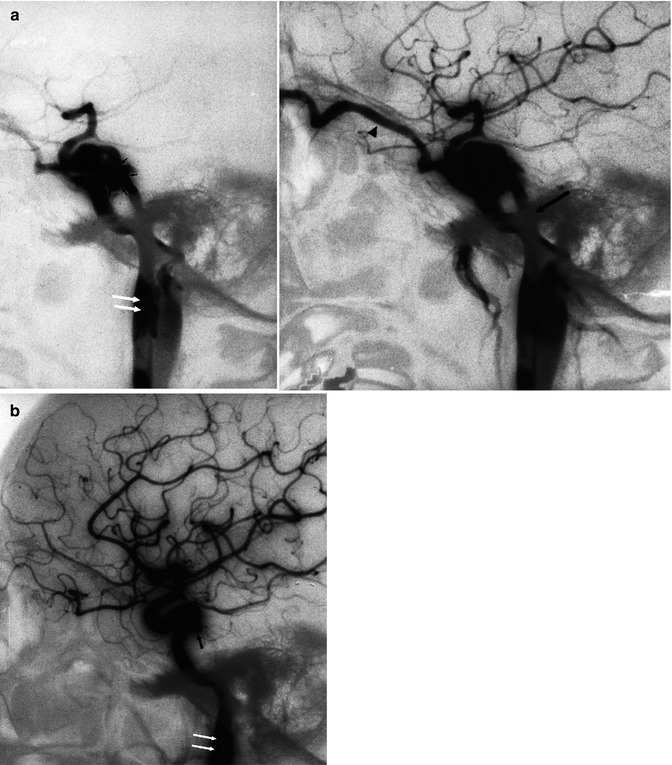

Fig. 14.2

Spontaneous carotid–cavernous fistula in a young patient, which appeared after heavy vomiting caused by alcohol intoxication. (a) Lateral carotid angiogram. The small arrows show the site of the shunt. There is drainage in the superior ophthalmic vein (arrowhead) and inferior petrosal sinus (arrow). There is also a minimal injection of the pterygoid plexus. The extracranial internal carotid artery is slightly enlarged, and there is an intraluminal defect (white arrows), suggesting dissection. It is possible that the dissection has extended intracranially, leading to formation of the fistula. The shunt was occluded with a balloon. (b) Control angiogram 2 months later. The balloon is now deflated. A small pseudoaneurysm (arrow) at the site of the fistula is recognizable. The dissection is unchanged (white arrow)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree