Approaches to and Management of Varicose Veins

Bhagwan Satiani

Maria Litzendorf

Varicose veins are a common problem with one quarter to one third of all adults in the western world affected by this disorder. Varicose veins can be asymptomatic (with purely aesthetic connotation) or can directly impact quality of life when associated with symptoms of heaviness, fatigue, or throbbing pain. Although usually found on the lower extremities, varicose veins can also be located in the upper extremity, trunk, vulva, spermatic cords (varicoceles), rectum (hemorrhoids), and esophagus (esophageal varices). Although primarily an adult condition, in rare cases, children can be affected, most commonly when associated with underlying vascular malformations such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Other congenital conditions such as Maffucci’s syndrome, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, or diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis may manifest with telangiectasia during childhood.

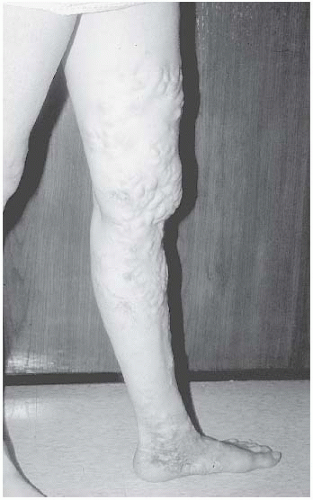

Varicose veins are generally identified by their tortuous, twisted, bulging, superficial appearance and can be grouped as truncal, reticular, or telangiectasia. Truncal varices (also known as stem or axial veins) refer to larger vessels including the great and small saphenous veins and their branches. Reticular veins are the smaller, superficial, blue-green, flat, tortuous vessels, while telangiectasias are the small blue-black or red veins that are less than 1 mm in diameter (Figs. 20.1 to 20.3).

The symptoms of varicose veins have often been ignored or underestimated by physicians in the past. In addition, treatment options were often limited. Fortunately, with the advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of venous disorders and the addition of newer diagnostic and treatment modalities, we are now better equipped to treat patients with varicose veins.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Incidence and Prevalence

Varicose veins are the most common clinical manifestation of chronic venous disease. However, the differing terminology and diagnostic criteria used in many epidemiological data sets make it difficult to accurately determine the prevalence of varicose veins in the general population. In addition, it is estimated that up to one third of patients never seek treatment for their varicose veins. Given these limitations, the incidence of varicose veins may be grossly underestimated. Despite this, most prevalence figures for pronounced disease range from 10 to 15%, and for all types of disease range from 30 to 50%. In the widely referenced Framingham study, the 2-year incidence of varicose veins was 39.4 new cases per

1,000 men and 51.9 cases per 1,000 women. While it is generally conceded that women are more likely to seek medical attention for varicose veins, most population studies still agree that varicose veins are two to three times more common in women, occurring in 25 to 46% of women and 7 to 19% of men.

1,000 men and 51.9 cases per 1,000 women. While it is generally conceded that women are more likely to seek medical attention for varicose veins, most population studies still agree that varicose veins are two to three times more common in women, occurring in 25 to 46% of women and 7 to 19% of men.

In addition, there are geographical, social, and ethnic factors that impact the prevalence of varicose veins. Industrialized populations tend to have higher prevalence rates than developing countries. In North and Sub-Saharan Africa, rates are one fourth to one fifth of that seen in European women. While these differences have been observed in epidemiologic studies, they are inconsistent in immigrant populations, suggesting that cultural factors including diet and exercise may play a more important role than genetics and geography.

Risk Factors

Table 20.1 lists risk factors that have been implicated in the development of varicose veins. A number of these factors are believed to mediate their effects through increases in lower extremity hydrostatic pressure directly or through an increase in intra-abdominal pressure with resultant compromise

in blood return to the iliac veins. The genetics of varicose veins is not understood, although it is believed that there is a genetic component that affects predilection. Commonly believed associations of varicose veins with high systolic blood pressure, congestive heart failure, diabetes, serum lipids, tight undergarments, and hernias have not been supported by populationbased studies. However, there is strong evidence that occupations involving prolonged standing including nurses, teachers, assembly-line workers, surgeons, and beauticians are associated with the development of varicosities. A BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2 carries a fivefold increase in the prevalence of varicose veins in women. Pregnancy is also frequently reported as a risk factor for the development of varicose veins. Although the enlarging uterus is believed to obstruct venous return and contribute to the formation of varicose veins, most women report an increase in varicose veins during their first trimester, when the gravid uterus is not yet large enough to cause mechanical obstruction. The role of estrogen on smooth muscle relaxation has been well described. Thus, women on oral contraceptives or those who are pregnant have increased venous distensibility and decreased venous tone, which may contribute to the development of venous disease. Women with multiple pregnancies also appear to have a higher prevalence of varicose veins.

in blood return to the iliac veins. The genetics of varicose veins is not understood, although it is believed that there is a genetic component that affects predilection. Commonly believed associations of varicose veins with high systolic blood pressure, congestive heart failure, diabetes, serum lipids, tight undergarments, and hernias have not been supported by populationbased studies. However, there is strong evidence that occupations involving prolonged standing including nurses, teachers, assembly-line workers, surgeons, and beauticians are associated with the development of varicosities. A BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2 carries a fivefold increase in the prevalence of varicose veins in women. Pregnancy is also frequently reported as a risk factor for the development of varicose veins. Although the enlarging uterus is believed to obstruct venous return and contribute to the formation of varicose veins, most women report an increase in varicose veins during their first trimester, when the gravid uterus is not yet large enough to cause mechanical obstruction. The role of estrogen on smooth muscle relaxation has been well described. Thus, women on oral contraceptives or those who are pregnant have increased venous distensibility and decreased venous tone, which may contribute to the development of venous disease. Women with multiple pregnancies also appear to have a higher prevalence of varicose veins.

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

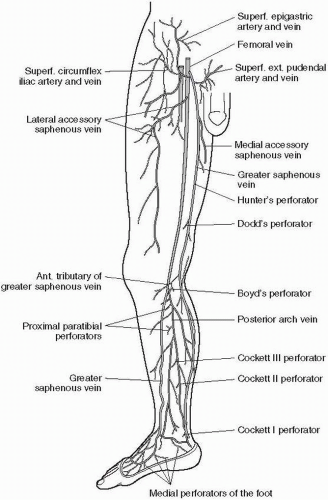

The terminology of the major veins in the lower extremities has been revised (Table 20.2) (Fig. 20.4). The venous system of the legs is divided into deep and superficial vessels. Perforator veins link the superficial to the deep veins and enable blood flow during muscle relaxation when pressure in the deep veins falls below that of the superficial vessels. Varicose veins are a common symptom of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI, see

Chapter 22) that develops as a result of a structural or functional defect in the venous system. These defects lead to ambulatory venous hypertension and can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary disorders affect the venous wall or valves and lead to reflux and venous dilatation without evidence for previous venous thrombosis. They are more common in women and most patients will report a strong family history for varicose veins. Secondary defects are the result of venous thrombosis that leads to obstruction, reflux, or a combination of the two. Venous hypertension is defined as end-exercise venous pressure at the ankle greater than 30 mm Hg (normal is 15 mm Hg) and can be measured (but is rarely done) using a 21-gauge needle. Measurements are made in a dorsal foot vein following 10 tiptoe movements at a rate of one per second as the venous pressures are lowest at the end of exercise. The severity of venous disease correlates excellently with the degree of venous hypertension. At pressures of less than 30 mm Hg, ulceration is rare, while at pressures of greater than 90 mm Hg, there is nearly a 100% incidence of ulceration.

Chapter 22) that develops as a result of a structural or functional defect in the venous system. These defects lead to ambulatory venous hypertension and can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary disorders affect the venous wall or valves and lead to reflux and venous dilatation without evidence for previous venous thrombosis. They are more common in women and most patients will report a strong family history for varicose veins. Secondary defects are the result of venous thrombosis that leads to obstruction, reflux, or a combination of the two. Venous hypertension is defined as end-exercise venous pressure at the ankle greater than 30 mm Hg (normal is 15 mm Hg) and can be measured (but is rarely done) using a 21-gauge needle. Measurements are made in a dorsal foot vein following 10 tiptoe movements at a rate of one per second as the venous pressures are lowest at the end of exercise. The severity of venous disease correlates excellently with the degree of venous hypertension. At pressures of less than 30 mm Hg, ulceration is rare, while at pressures of greater than 90 mm Hg, there is nearly a 100% incidence of ulceration.

TABLE 20.1 RISK FACTORS FOR VARICOSE VEINS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 20.2 OLD AND NEW TERMINOLOGY OF LOWER EXTREMITY VEINS | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Histologic examination of varicose veins demonstrates disorganization of the muscular layers, with a thickened intima, and fibrosis between the intima and the adventitia. In addition, there is atrophy of the elastic fibers. These histologic changes reiterate the importance of these structural alterations in mediating the functional consequences of reduced contractility and loss of compliance. Subsequent dilatation causes a separation of valve cusps within the vein and results in valvular incompetence or reflux. Secondary defects are a result of valve cusp damage from previous thrombotic episodes. Varicose veins are more likely to develop where the superficial and deep systems communicate, for example, at the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junctions or where perforator veins connect the two systems.

Symptoms and Signs

Table 20.3 lists the presenting symptoms and signs. Varicose veins are associated with varying degrees of pain and swelling. The pain is often described as aching, tingling, or cramping in nature. Common complaints include fatigue, restlessness, burning, stinging, itching, tension, or heaviness in the legs.

Symptoms are generally less severe in the morning but exacerbated with prolonged standing or sitting throughout the day. Consequently, symptoms tend to resolve with rest and elevation. The most common symptom reported by women is aching, while men report cramping pain more often. Varicose veins may be exacerbated during menses or first noted with pregnancy. Women

may experience pelvic pain or dyspareunia due to vulvar varices. Symptoms do not always correlate with the size or number of veins and, at times, may seem inconsistent with the physical examination. Patients with small varicosities may complain of a severe burning pain, heaviness, or swelling, while patients with larger varices may be asymptomatic. Patients without symptoms often seek medical attention for cosmetic reasons or simply reassurance about their condition. Approximately 5 to 7% of patients with venous disease seek medical attention because of complications, including superficial venous thrombosis (SVT), bleeding, and ulceration. When bleeding does occur, it is often profuse and may be mistaken for an arterial bleed because of high venous pressure. It is often spontaneous, although it can occur after such minor trauma as shaving the legs.

Symptoms are generally less severe in the morning but exacerbated with prolonged standing or sitting throughout the day. Consequently, symptoms tend to resolve with rest and elevation. The most common symptom reported by women is aching, while men report cramping pain more often. Varicose veins may be exacerbated during menses or first noted with pregnancy. Women

may experience pelvic pain or dyspareunia due to vulvar varices. Symptoms do not always correlate with the size or number of veins and, at times, may seem inconsistent with the physical examination. Patients with small varicosities may complain of a severe burning pain, heaviness, or swelling, while patients with larger varices may be asymptomatic. Patients without symptoms often seek medical attention for cosmetic reasons or simply reassurance about their condition. Approximately 5 to 7% of patients with venous disease seek medical attention because of complications, including superficial venous thrombosis (SVT), bleeding, and ulceration. When bleeding does occur, it is often profuse and may be mistaken for an arterial bleed because of high venous pressure. It is often spontaneous, although it can occur after such minor trauma as shaving the legs.

TABLE 20.3 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF VARICOSE VEINS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Physical findings that frequently accompany varicose veins include edema, ulceration, dermatitis, hyperpigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, atrophie blanche, hemorrhage, and SVT. Hyperpigmentation and ulceration are classically found on the medial side of the ankle (gaiter area) but may also occur in the lateral aspect of the leg above the malleolus (associated with small saphenous vein incompetence). Hyperpigmentation results from hemosiderin deposition within dermal macrophages after the breakdown of red blood cells.

Venous ulcers may be difficult to heal and are frequently recurrent (Fig. 20.5). Lipodermatosclerosis, also known as stasis cellulitis,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree