Light’s criteria

Value

Pleural fluid to serum protein ratio

>0.5

Pleural fluid to serum LDH ratio

>0.6

Pleural fluid LDH concentration

>2/3 upper limit of lab normal value

Table 65.2

Studies evaluating light’s criteria

Study | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Light (1972) | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | |

Meisel (1990) | 90 | 82 | 86 | 87 | |

Roth (1990) | 100 | 72 | |||

Valdez (1991) | 95 | 78 | 91 | 95 | 80 |

Romero (1993) | 98 | 77 | 95 | ||

Burgess (1995) | 98 | 8,378 | 93 | 93 | 96 |

Costa (1995) | 98 | 82 | |||

Vives (1996) | 99 | 78 | 95 | 95 | 93 |

Causes of Pleural Effusions

The differential diagnosis of pleural effusions is extensive which at least partially explains the need to divide effusions into exudates and transudates to reduce the diagnostic possibilities.

The most common causes of transudative effusions include congestive heart failure and cirrhosis. Other less common causes include renal disease (nephrotic syndrome, glomerulonephritis, and peritoneal dialysis), hypoalbuminemia, and myxedema. In less than 10% of cases, malignant effusions may be transudative as are less than 35% of effusions related to pulmonary emboli. With respect to exudative effusions, the most common causes include malignancy (either primary lung or metastatic), infectious (parapneumonic, empyema, or pleural tuberculosis), connective tissue diseases, and post-cardiopulmonary bypass. Refer to Table 65.3 for a comprehensive list of causes of transudative and exudate effusions.

Table 65.3

Causes of transudative versus exudate pleural effusions

Transudative | Exudative |

|---|---|

– Congestive heart failure | – Malignancy |

– Nephrotic syndrome | Primary, mesothelioma, or metastatic |

– Cirrhosis | – Infection |

– Hypoalbuminemia | Parapneumonic, empyema, or tuberculous |

– Peritoneal dialysis | – Connective tissue disease |

– Glomerulonephritis | Systemic lupus, rheumatoid arthritis |

– Urinothorax | – Post-coronary artery bypass graft |

– Atelectasis | – Pulmonary embolism |

– Trapped lung | – Chylous |

– SVC obstruction | Disruption of thoracic duct or lymphoma |

– Constr. pericarditis | – Subdiaphragmatic |

– Malignancy (<5%) | Pancreatitis, abscess, or benign ovarian tumor |

– Pulmonary embolus (<35%) | – Yellow nail syndrome |

– Myxedema | – Medication related |

– Sarcoidosis | – Benign asbestos pleural effusion |

Clinical Approach to Pleural Effusion

A comprehensive history and physical examination are essential in the evaluation of patients with pleural effusions. In many cases, the cause of the effusion may be suspected based simply on the findings of the clinical assessment obviating the need for further diagnostic testing. If, for example, a patient has evidence of congestive heart failure, then it is quite appropriate to treat the heart failure as a therapeutic challenge to determine whether the effusion is responsive to diuretics. In the case of a refractory effusion in this setting, then one may consider a more extensive diagnostic work-up of the effusion.

Pleural effusions often present with dyspnea depending on the size of the effusion at presentation. Pleuritic chest pain however may be indicative of pleural inflammation from causes such as infection, pulmonary emboli, or serositis. When pleurisy is associated with other symptoms of infection such as productive cough and fever, then one must be suspicious of a parapneumonic effusion or empyema. The presence of constitutional symptoms may suggest a systemic disease, chronic infections such as tuberculosis or alternatively malignancy. In addition, hemoptysis may be concerning for malignancy or pulmonary emboli. An extensive exposure and travel history may suggest malignancy, asbestos-related pleural disease, or tuberculosis. Past medical and family history may also be quite revealing as well as a careful overview of the patient’s medication list. The list of medications leading to pleural effusions is quite lengthy and beyond the scope of this review. The website www.pneumotox.com is a valuable resource to identify pulmonary and pleural manifestations attributable to medications.

Systemic manifestations should be sought out as they may lead to a diagnosis of connective tissue disease, hypothyroidism, or heart failure. Concern should be raised for inflammatory, infectious causes, or pulmonary infarct if the patient presents with a pleural friction rub. Another consideration is the size and symmetry of the pleural effusion. Nearly 70% of massive effusions are malignant. Bilateral effusions are most suggestive of congestive heart failure although may be present in malignancy, connective tissue disease, drug reactions, infection, and renal disease.

Chest Imaging

Chest imaging can provide invaluable information regarding the nature of the pleural effusion. This includes the location, size, and flow characteristics of the effusion. The posteroanterior (PA) film is the standard first-line imaging technique and is able to identify even a small quantity (approximately 200 ml on PA and 50 ml on lateral projection) as blunting of the costophrenic angle. As stated above, very large fluid collections are most commonly attributable to malignancy. The plain radiograph may also give clues as to the etiology of the effusion, for example, an obstructing lesion in the bronchus (Fig. 65.1).

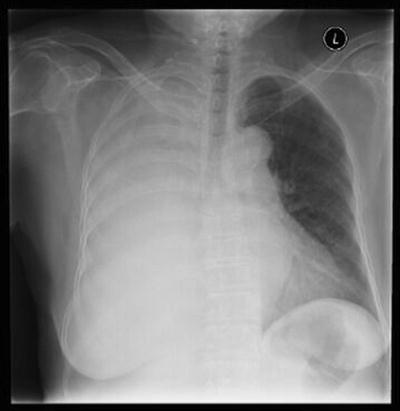

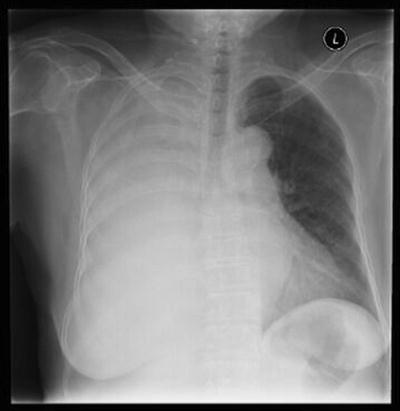

Fig. 65.1

Posteroanterior chest projection of a patient with a large pleural effusion and an obstructing endobronchial lesion resulting in the mediastinum being fixed in the center as well as a cutoff sign of the right main bronchus

The role of computed tomography (CT) in the management of patients with unclear exudates is limited to the identification of other pathologies that may be leading to the pleural effusion. The decision to perform a CT of the chest will depend on the clinical context and suspicion of an etiology requiring this procedure for diagnosis, for example, pulmonary embolus. Additional imaging may also be beneficial should the pleural fluid analysis fail to reveal the cause of the effusion.

Pleural Fluid Analysis

Fluid Characteristics

Pleural fluid analysis is the first initial invasive diagnostic test to be performed in an undiagnosed pleural effusion. The approach to thoracentesis is the subject of different section of this text and therefore will not be discussed in detail.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree